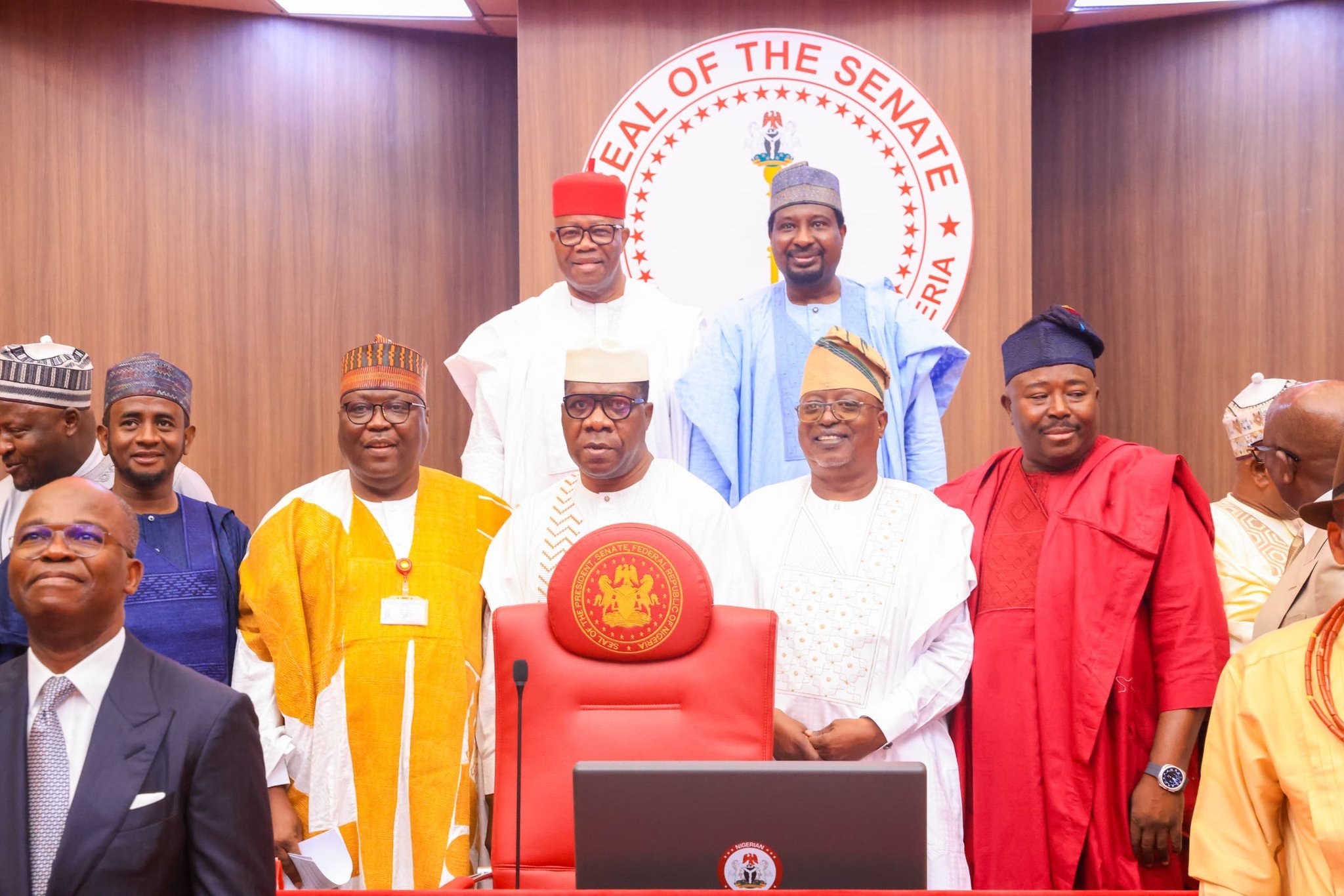

Some APC senators in a group photograph with Samaila Dahuwa Kaila who defected from the Poeples Democratic Party (PDP)

Nigeria’s 2023 general election delivered one of the most competitive senate contests since 1999 — a chamber once hailed as the country’s last line of institutional independence.

When the 10th senate convened in June 2023, no single party held an overwhelming majority. The All Progressives Congress (APC) secured 59 of the 109 seats, the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) had 36, while the Labour Party (LP) clinched eight. The Social Democratic Party (SDP), New Nigeria Peoples Party (NNPP), and the All Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA) completed the lineup with one or two seats each.

That composition made consensus and cross-party negotiation indispensable. But two years later, defections have radically altered the arithmetic.

A SLOW DRIFT TO DOMINANCE

Advertisement

The tide began to turn when internal crises rocked the opposition parties. Senators frustrated by factional battles and leadership wrangling started crossing over to the ruling party.

The most recent defection came from Kelvin Chukwu, senator representing Enugu east, who dumped the LP for the APC.

Chukwu was followed by Kaila Samaila, senator representing Bauchi north, who defected from the PDP to the APC.

Advertisement

About 48 hours after Samaila’s move, Benson Konbowei, senator representing Bayelsa central, resigned from the PDP and joined the APC.

Their switch brought the ruling party’s tally to 75 senators — more than two-thirds supermajority.

“Recent developments in the Labour Party at both the state and national levels have made it difficult for me to represent my constituents under its banner,” Chukwu said in a letter read by Senate President Godswill Akpabio.

Samaila said his decision to leave the PDP was driven by the party’s internal challenges, which had “gravely constrained” his ability to serve his constituents effectively.

Advertisement

Konbowei said he had lost faith in the PDP’s capacity to function as an effective opposition or win elections in the country.

Their move followed similar exits by Francis Fadahunsi (Osun east), Oluwole Olubiyi (Osun central), Aniekan Bassey (Akwa Ibom north-east), and Samson Ekong (Akwa Ibom south) — all PDP senators who joined the APC amid intraparty rancour.

THE NEW NUMBERS

As of today, the senate’s composition stands as follows: APC – 75 seats | PDP – 26 | LP – 4 | APGA – 2 | NNPP – 1 | SDP – 1.

Advertisement

This numerical dominance now gives the ruling party the leverage to push through constitutional amendments, appointments, and emergency proclamations with minimal resistance.

THE RIVERS STATE EMERGENCY RULE CONTROVERSY

Advertisement

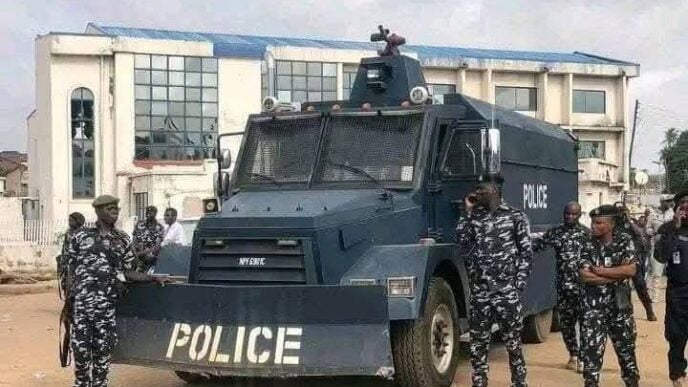

The senate’s power dynamics were laid bare during the recent debate on President Bola Tinubu’s request for emergency rule in Rivers state.

Constitutionally, a two-thirds majority of all senators is required to approve such a proclamation under Section 305(6b) of the 1999 Constitution.

Advertisement

When it seemed the ruling party could not get the numbers, the senate leadership adopted a voice vote instead of a recorded division, sparking outrage from opposition senators who claimed the process lacked transparency.

Ireti Kingibe, senator representing the federal capital territory, described the method as “unconstitutional and opaque”, arguing that “a voice vote cannot replace the numerical verification required by the constitution”.

Advertisement

Seriake Dickson, senator representing Bayelsa west, also alleged that dissenting voices were “silenced”, claiming that “the leadership was determined to give the president what he wanted.”

The episode revived concerns that the upper chamber was becoming a pliant tool of the executive.

With the ruling APC now having more than a two-thirds majority in the upper chamber, such questionable declaration from the president can easily pass through the senate without any resistance — a rubber-stamp chamber, some would reiterate.

CHECKS AND BALANCES UNDER STRAIN

Political analysts further confirmed that the senate’s current configuration hands the presidency unprecedented control over legislative outcomes.

With 75 loyal senators from the ruling APC, the executive now commands the two-thirds majority required to approve constitutional amendments, state of emergency declarations, or major policy reforms — a situation critics fear could erode democratic accountability.

“The implication of this is that you get an imbalanced house,” Samuel Folorunsho, executive director of Legis360 AI, told TheCable.

“Now, bills can be passed without the minority. Because once you get two-thirds, the minority cannot oppose anything. If they decide to stage a walkout on any issue now, it is meaningless.

“Also, the narrative around a one-party system is now solidified. It also shows political instability and how politicians are willing to leave a position of power to guarantee themselves a seat in the next election.

“It also shows that governance only exists for a year out of the four years we have, because all the political moves we are beginning to see is towards 2027, which may now mean governance will begin to suffer.”

Even without a two-thirds majority, observers said the 10th national assembly has failed to meet public expectations.

“What’s the point of having an opposition in the senate when every bill from the executive passes without resistance?” asked Kelechi Uche, an economist, in a post on X.

He added that the 10th national assembly “will go down in history as the most ineffective”.

BEYOND THE NUMBERS

While party defections are not new to Nigeria’s democracy, the scale of realignment in the 10th senate is unprecedented.

The APC’s legislative supermajority may guarantee smoother relations with the executive, but it also raises profound questions about oversight and pluralism.

Unless new rules — such as mandatory roll-call votes for constitutional matters — are enforced, the senate risks being remembered not for its debates but for its deference.

From the hotly contested 2023 elections to the recent wave of defections, Nigeria’s upper chamber has undergone a quiet metamorphosis.

Once a forum for rigorous debate, it now stands at risk of becoming an echo chamber — one where the voice of the executive is the loudest and, increasingly, the only one that counts.