It sounded exactly like her, but it was not. Adeola Fayehun was thousands of miles away in the United States when the calls began. First, a friend phoned in a panic, his voice laced with fear: “Adeola, are you really stranded in Lagos? How much do you need?”

The voice on the other end had been hers, eerily precise. Every word mimicked her tone. Even the subtle Yoruba inflection was a replica of Adeola’s speech.

Her friend, guided by suspicion, played along. But when he did not fall for the ruse, the impersonators, still speaking in Adeola’s cloned voice, launched into curses.

Then came the WhatsApp attack. This time, it was a cloned voice identical to her uncle’s, demanding urgent verification codes.

Advertisement

Adeola almost fell for it. The voice was so familiar and had her on the brink of complying. However, her uncle’s tone grew harsh, and that subtle shift was the red flag. She suddenly realised that her uncle would never speak to her that way.

Adeola’s story, though harrowing, barely scratches the surface of Nigeria’s burgeoning digital vulnerability.

She escaped the trap. Many others have not been so lucky.

Advertisement

According to a 2023 McAfee global survey, one in ten people have been targeted by AI voice cloning scams, and 77 percent of them have lost money.

In Nigeria, scammers are already capitalising on this trend. One familiar case involved a French broadcaster who lost her life savings to a Nigerian impersonator pretending to be actor Brad Pitt. She transferred €830,000 to the scammers, who sent her fake photos and videos.

The Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) indicated it could act on the matter, but only if the victim stepped forward. This was a promise dressed in procedure, one that sounded official yet hollow.

Behind the assurance was an uncomfortable truth: even if a case were filed, the law offers no firm footing for AI-powered impersonations.

Advertisement

There is no explicit mention of AI-generated likenesses. No specific clause for deepfakes. No legal teeth for impersonations manufactured or enhanced by machine. The specific tools and definitions to prosecute crimes orchestrated by AI simply do not exist.

THE LEGAL VACUUM

The Cybercrime Act, passed in 2015, was meant to safeguard Nigeria’s digital ecosystem. But its focus remained on conventional threats like hacking, online fraud, data breaches, and defamatory online content.

A supposed leap forward came in 2024 with an amendment meant to modernise the law. However, what emerged was a cosmetic patch to an ageing legal framework.

Advertisement

The updates failed to address the known AI threats the world is now grappling with, not even a mention of how global AI platforms, trained on user data, might exploit Nigerian citizens or what consequences such misuse would carry.

Rebecca Etusi, a Nigerian tech lawyer, told TheCable that the 2024 amendment did little to close the regulatory gaps.

Advertisement

She said that while Section 24(1)(b) targets harmful falsehoods, it was not designed with AI-generated content in mind.

“The 2024 amendment to Nigeria’s Cybercrime Act makes only limited progress in addressing today’s fast-changing online threats, especially the growing use of AI deepfakes,” she said.

Advertisement

“A key amendment is Section 24 (1) (b), which amends the definition of cyberstalking. It criminalises the sending of messages or information known to be false, for the purpose of causing a breakdown of law and order and posing a threat to life.

“I say this amendment is key because, although not labelled as AI-powered, this definition accommodates the content generated through AI and activities perpetuated with the use of AI systems.”

Advertisement

Etusi added that Section 13, which addresses computer-related forgery, still speaks mostly to outdated forms of digital fraud. She said the law lacks the precision for emerging threats, and applying it to AI content would demand legal acrobatics unlikely to stand in court.

WEAPONISATION OF THE LAW

Her concerns echo those of Solomon Okedara, a digital rights lawyer who once challenged Section 24’s constitutionality in Okedara v. Attorney General of the Federation.

“Even after the amendment, Section 24 still threatens dissent and press freedom,” Okedara said.

The law, in theory, was built to shield the digital space from predators. In practice, it has become a weapon to muzzle critics and “cyberstalking” serves as the government’s catch-all phrase.

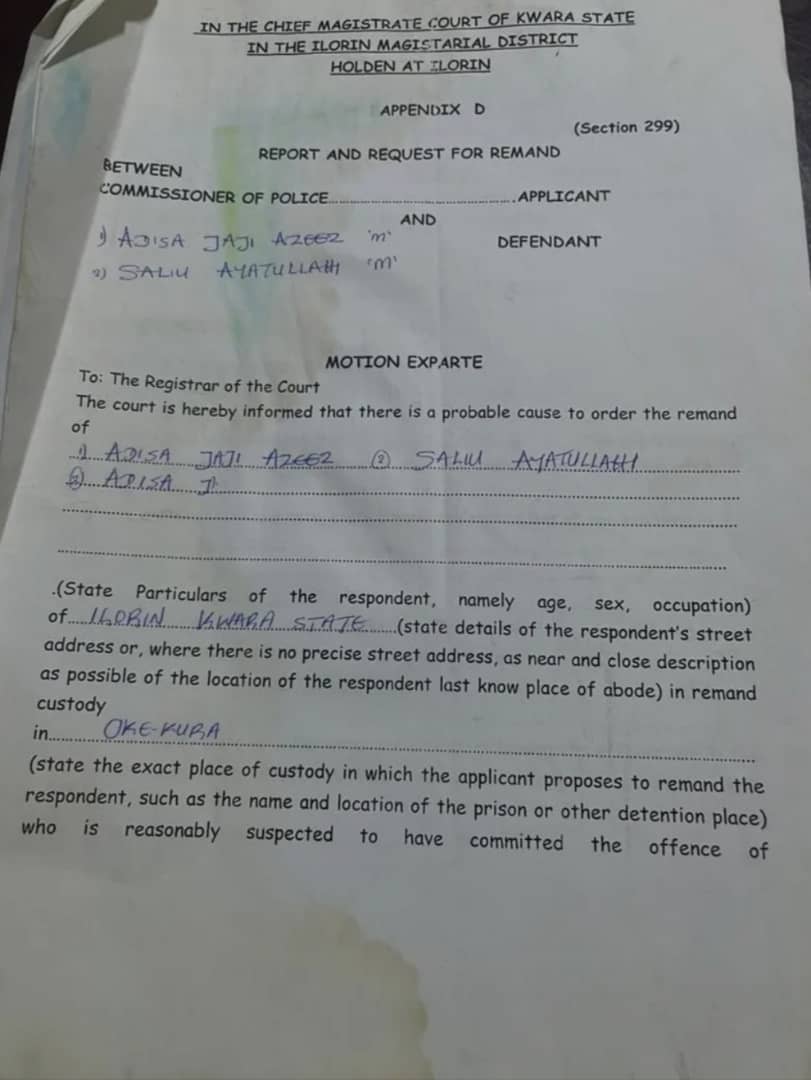

In 2024, Salihu Ayatullahi, a journalist, was arrested for cyberstalking after reporting alleged corruption at Kwara State Polytechnic. The charges were dropped, but only after days in detention, financial loss, and reputational harm.

He is not alone. Since the Act came into force, at least 29 journalists have been prosecuted under broad provisions like “cyberstalking” or “knowingly false messages”.

In most cases, no hacking occurred, nor was data breached.

Naro Omo-Osagie, who leads Africa policy and advocacy at Access Now, a global watchdog for digital rights and tech regulation, highlights Section 24’s vague definition of “cyberstalking” as a major concern, noting that it “falls well short of international standards, which demand precision and clarity in criminal law to prevent abuse”.

She said the ECOWAS court in 2022 ruled that Section 24 violates human rights, yet the 2024 amendments failed to rectify this flaw.

Omo-Osagie stressed that the priority in regulating technologies like AI must be the implementation of “robust human rights safeguards”. She also warned that expanding the Cybercrime Act without fixing its foundational issues, especially concerning privacy, free expression, and due process, would be “very dangerous”.

NIGERIA’S UNFINISHED FIGHT AGAINST CYBERCRIME

The urgency for legislative reform is underscored by Nigeria’s unenviable position in the global cybercrime landscape.

In 2023, Nigeria ranked among the world’s top five countries for reported cybercrime complaints. The International Criminal Police Organisation (INTERPOL) recorded a 23 percent year-on-year increase in cyberattacks across Africa, with AI playing a leading role in phishing, identity theft, and impersonation.

Nigeria also ranked third in Africa for ransomware detections in 2024, with 3,459 incidents.

INTERPOL’s 2025 Cyberthreat Report flagged Nigeria as a major origin point for AI-powered scams, including romance fraud, business email compromise (BEC), and sextortion using AI-generated images. Groups like Black Axe have turned these into multimillion-dollar operations across West Africa.

The report also noted a 60 percent increase in digital sextortion, many involving AI-generated images, across African member countries.

A wall of silence greets anyone seeking Nigeria’s AI-powered cybercrime data. For this report, repeated requests to the EFCC and the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC) were met with silence.

However, two police officers, including a source at the State Criminal Investigation Department (SCID), Panti, agreed to speak off the record.

One of the officers painted a bleak picture of the practical challenges within the force.

He said: “I won’t lie to you. We do not have the training. We do not have the tools in our divisions. Most officers do not even understand what AI is; all we have is pen and paper.”

When asked if the absence of AI-specific provisions in Nigeria’s Cybercrime Act makes enforcement harder, the SCID source initially said, “the law actually covers these threats, maybe not directly”.

Then, after a telling pause, he added: “But truthfully, we’re still catching up, we have a long way to go.”

He also noted that the problem is not just legal but cultural.

“People call these criminals ‘hustlers’. They do not see cybercrime as a real crime,” he said, recounting raids where crowds protested arrests.

The SCID officer revealed that the department has gone years without proper tools or funding. Investigations are often self-funded, relying on free, open-source tools.

“We are not being funded. Even the tools we do have are self-funded,” he added.

“We make use of open-source intelligence tools. Cellebrite was removed from the market because it was too expensive. These tools are costly, let alone the cost of maintaining them”.

GLOBAL RESPONSES

As Nigeria contends with an outdated legal framework, across the globe, governments are rewriting their rulebooks and crafting specific laws to confront the risks posed by AI.

In 2024, the European Union (EU) passed the world’s first dedicated AI law, classifying systems by risk and mandating clear labels for synthetic content.

South Korea followed in January 2025 with its AI Basic Act, requiring ethical standards, transparency, and oversight across all AI systems.

Brazil’s lawmakers are pushing Bill No. 2,338/2023 to hold developers accountable for AI-related harm, especially from deepfakes and automated scams.

In the United States, Tennessee passed the ELVIS Act in 2024 to criminalise unauthorised AI voice and image cloning.

Even within Africa, tailored AI governance is taking shape.

Rwanda rolled out a full National AI Policy in 2023, focused on ethics, data protection, and digital literacy.

The African Union adopted its first Continental AI Strategy in July 2024, urging member states to embed ethical principles and responsible innovation in AI development.

South Africa unveiled its National AI Policy Framework in August 2024, anchored on 12 pillars—from transparency to national security.

Kenya, in March 2025, launched its AI Strategy for 2025–2030, built around three pillars: digital infrastructure, data, and AI innovation, all backed by agile, ethics-driven regulation.

Nigeria’s 2024 cybercrime law update mentions none of these.

COPY-AND-PASTE PROBLEM

Much of Nigeria’s digital legislation mirrors global frameworks that are now racing ahead with reforms.

Omo-Osagie says this “copy-paste” strategy is part of the problem. “Laws do not exist in theory,” she said. “They operate in real, and often complex systems.”

According to her, Nigeria’s digital laws fail not just because they are outdated, but because they were never locally grounded from inception.

Imported frameworks, she said, rarely reflect everyday life in Nigeria, where many still struggle with internet access, surveillance tools are acquired with little transparency, and big tech companies face almost no consequences for bad behaviour.

“We have seen governments justify abusive laws by claiming they are defending traditional values or national security,” Omo-Osagie said.

“That is dangerous. Context-sensitive regulation means more precision, not more vagueness. It means writing laws that actually protect people, especially the most vulnerable, and not giving officials more unchecked power.”

She warned that without meaningful local engagement, especially from civil society, future AI regulations risk becoming yet another copy of foreign blueprints, ill-suited to Nigeria’s fragmented infrastructure and sociopolitical terrain.

“Good AI governance must be multistakeholder, transparent, and intentionally inclusive, not just designed to look good on paper, but to actually work in practice,” she added.

THE BURDEN OF AWARENESS

In the absence of legal clarity and institutional guardrails, it is now victims who are sounding the alarm.

Adeola, nearly scammed by her own cloned voice, is one of many urging the public to “never read that code out loud”.

“People can now use AI to clone anybody’s voice,” she warned. “Even if it sounds like someone you know, just do not do it.”

It should not have to be this way. But when the law does not speak to modern threats, the burden of awareness shifts to those already burned, instead of the systems meant to protect them.

This report was produced with support from the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID).