BY OLUMAYOWA OLANIYI

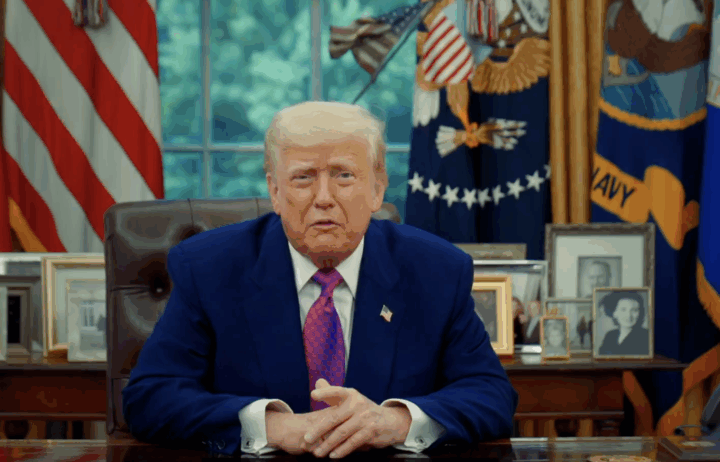

Ever since U.S. President Donald Trump, on the 31st of October 2025, declared Nigeria a Country of Particular Concern (CPC) and suggested that the United States might intervene militarily to “protect persecuted Christians”, the country has witnessed a troubling escalation in violent attacks across several northern states. In the weeks following Trump’s statement, Nigeria has experienced a string of coordinated assaults, like school abductions, church invasions, village raids, and even clashes between insurgent factions, which have deepened public anxiety and raised urgent questions about what exactly is driving this sudden wave of bloodshed.

Almost immediately after the CPC designation, gunmen attacked villages along the Plateau-Kaduna border, killing at least seventeen residents in coordinated nighttime assaults that left scores displaced. What followed was a grim cascade of violence. In Kebbi State, armed men stormed a girls’ secondary school in Maga, killing the vice principal and abducting twenty-five schoolgirls, an incident that reignited memories of past mass gender-targeted kidnappings.

In Kwara state, a church was raided during a livestreamed service, leaving several worshippers dead and the pastor and congregants abducted, prompting authorities to shut down schools in parts of the state. Sokoto has seen a succession of attacks, as fifteen people were abducted in Kurawa, nine kidnapped in Tarah, and two killed in Kabunga, including a former councillor. In the north-east, Boko Haram and ISWAP engaged in a ferocious battle near Dogon Chiku that reportedly left about two hundred fighters dead and the killing of the Brigadier General. And in Taraba’s Amadu community, nearly thirty people were killed in less than two weeks, while in Kaduna’s Kagarko area a Catholic priest was kidnapped and another civilian killed.

This rapid succession of attacks has compelled many Nigerians to ask whether Trump’s CPC designation may have played a role in altering the behaviour of armed groups. Though the statement came from outside Nigeria, its implications reverberate internally and globally as Nigeria also gained some sympathisers against the statement of President Trump. Armed groups, whether ideological insurgents or criminal networks, are acutely sensitive to geopolitical narratives. Trump’s assertion that Nigerian Christians are under siege, and his insinuation that Washington might intervene, may have encouraged certain extremist factions to escalate violence, either to validate the narrative of religious persecution or to embarrass the Nigerian government on the global stage. For groups seeking attention, legitimacy or relevance, a moment of heightened international focus can become an incentive to intensify operations. Equally, the deadly turf war between Boko Haram and ISWAP near Lake Chad suggests that extremist factions may be reacting not just to local dynamics but to shifts in the global spotlight.

Advertisement

But the surge in violence cannot be attributed to Trump’s declaration alone. Nigeria is moving toward the 2027 elections, and the pre-election environment has historically been fertile ground for insecurity. Political actors sometimes mobilise militias and armed youth groups to consolidate territorial influence, while terrorists and bandit groups exploit the state’s divided attention. The recent pattern of assaults targeting rural communities, symbolic institutions like schools and churches, and key localities across the north-west and north-central aligns with previous cycles in which violence becomes a means of shaping negotiations, intimidating populations, or asserting political leverage.

At the same time, Nigeria has recently undergone a shift in the leadership of its Armed Forces, a transition that may have created temporary operational gaps. Changes at the top often lead to reviews of existing strategies, reassignment of field commanders, and restructuring of operational directives. Even short pauses in counterterrorism operations can be exploited by well-organised non-state armed groups. Recent attacks with their speed, coordination and boldness suggest that insurgents and bandits may have acted during a period of military recalibration, taking advantage of reduced coherence or clarity in frontline operations. The announcement for the change of service chiefs was made on the 24th of October, while President Trump’s designation of Nigeria as CPC came on the 31st of October after alleging the Nigerian government and its military of complicity. This timeline raises several questions in the minds of Nigerians and the global audience.

The escalation in violence also forces Nigeria to confront several deeper, systemic questions. One of the most pressing is whether armed groups are gaining access to new sources of financing. The sophistication and frequency of the recent attacks suggest that bandit networks, insurgent factions and local militias may be benefiting from strengthened kidnapping-for-ransom economies, cross-border criminal alliances, or external ideological sponsorship. Another critical question concerns the weakening of local intelligence structures. In many rural communities, early warning depends not on formal security agencies but on local vigilantes, hunters, and CJTF operatives. When these networks are overstretched or disconnected from the security services, communities become exposed to attack.

Advertisement

Socioeconomic pressures also cannot be ignored. Nigeria’s worsening economic situation, rising unemployment, shrinking agricultural income and increasing displacement have created a fertile environment for recruitment into armed groups. Many young men are drawn to these groups because they offer income, identity or a form of power otherwise inaccessible. Adding to this is the persistent proliferation of small arms across northern Nigeria. The ease with which attackers move across borders, arrive on motorcycles and unleash violence before melting into forests or border communities highlights the scale of the arms-trafficking crisis.

There is also the uncomfortable question of whether Nigeria’s security narratives have been oversimplified by both domestic and international actors. Trump’s framing of the violence as primarily religious ignores the fact that in many regions, both Christians and Muslims are victims of the same predatory networks. Some attacks indeed target Christian villages and churches; others strike Muslim farming communities, transport routes and local markets. If Nigeria adopts a singular narrative, it risks addressing only one dimension of a multi-layered conflict.

All these questions point to a crisis that is far more complex than any one trigger. Nigeria’s insecurity today is a convergence of geopolitical tension, domestic political contestation, military transition, economic hardship, institutional weakness and structural fragmentation. But acknowledging this complexity is the first step toward meaningful action.

Trump’s CPC designation may not be the origin of Nigeria’s insecurity, but it has unquestionably shaped the present moment. It has placed Nigeria under a renewed global spotlight, influenced the behaviour of violent groups and sparked domestic debate at a time when the country is already grappling with political transition and structural fragility. As Nigeria approaches a critical election cycle, the stakes are higher than ever. The choices made now by the government, security institutions, political actors, communities and international partners will determine whether the country deepens its descent into violence or charts a path toward greater stability.

Advertisement

Olaniyi writes from Abuja and can be reached via [email protected]

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.