Illustration: Akila Jibrin/HumAngle

Across Nigeria’s conflict zones, death, displacement, and despair are everywhere. Despite claims that Christians face extermination, data reveal a far more complex and urgent reality.

Nigeria’s security crisis gained ascendancy about two decades ago when Boko Haram terrorism emerged in the northeastern region. The crisis, which has spiralled across the country, also reveals contradictions between reality and perception that often undermine the issues and hinder efforts to resolve them.

Over the past five years, HumAngle, with reporters on the ground, has mostly covered all kinds of armed conflicts and their effects across the country: south-south, south-east, south-west, north-east, north-central, and north-west. Violence has had a greater impact on Nigeria’s northern states, which are mostly Muslim but also have large Christian communities and many different minority groups.

While southern states have not been spared the acts of violence by militant and terrorist groups, their populations have been less affected in terms of displacement and the aftermath, such as refugee management.

Advertisement

In the northern region, the ongoing insecurity continues to disproportionately affect civilians of all faiths, ethnicities, and income levels. The prolonged crisis has caused entire communities to become unstable, with people losing their homes, lives, and livelihoods and retiring to displacement camps or taking shelter with host communities.

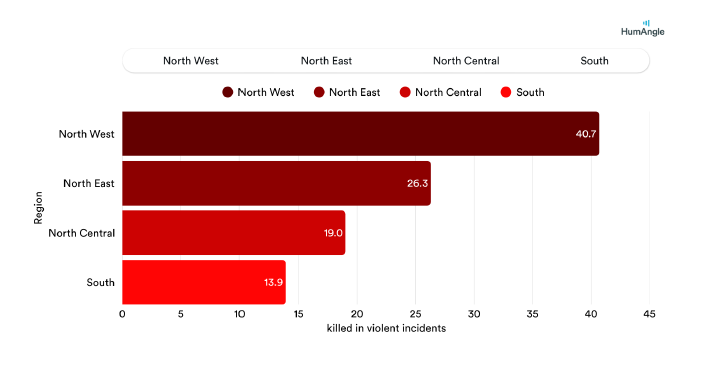

In 2024, according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), about 9,662 people were killed in violent incidents nationwide. Of these, about 86 per cent died in the northern part of the country, which is divided into regions with the following percentages: North West, 41.0 per cent; North East, 25.9 per cent; North Central, 19.3 per cent; and southern states, 13.8 per cent.

This persistent, geographic, and actor-driven pattern makes it difficult to reduce Nigeria’s crisis to just a religious frame.

Advertisement

What ‘genocide’ actually means

Genocide, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, means “the deliberate killing of a large number of people from a particular nation or ethnic group with the aim of destroying that nation or group.”

The 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide provides a more specific and legal definition: “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group”.

These acts, according to the convention, include: killing members of the group, causing serious bodily or mental harm, deliberately inflicting conditions of life calculated to bring about physical destruction, imposing measures to prevent births, and forcibly transferring children of the group to another group. One of the most recognised examples is the 1994 Rwandan genocide, during which extremist Hutu militias killed several Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

Advertisement

By these legal and linguistic standards, genocide requires both the intentional and systematic targeting of a group as such. These criteria provide a framework for examining claims about Nigeria’s complex violence.

Arguments for and against Christian genocide

In Nigeria’s north, particularly in the middle belt (north-central), communities that are predominantly Christian have faced repeated attacks by armed herders and militias, resulting in several killings and the forced displacement of many who are now in government-run and makeshift camps.

Similar attacks have been carried out in the north-east, where people died and religious centres, including churches, were destroyed. Boko Haram has equally released dozens of videos showing the beheading of Christians, including that of Lawan Andimi, the then chairperson of the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) in Adamawa state, on Jan. 20, 2020.

Advertisement

Furthermore, attacks in Southern Kaduna, Benue, and Plateau often pit herders believed to be associated with the Muslim faith against farming communities, which are largely Christian. The CAN and the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) have labelled these killings genocidal due to their large scale, selective nature, and the lack of punishment for the perpetrators.

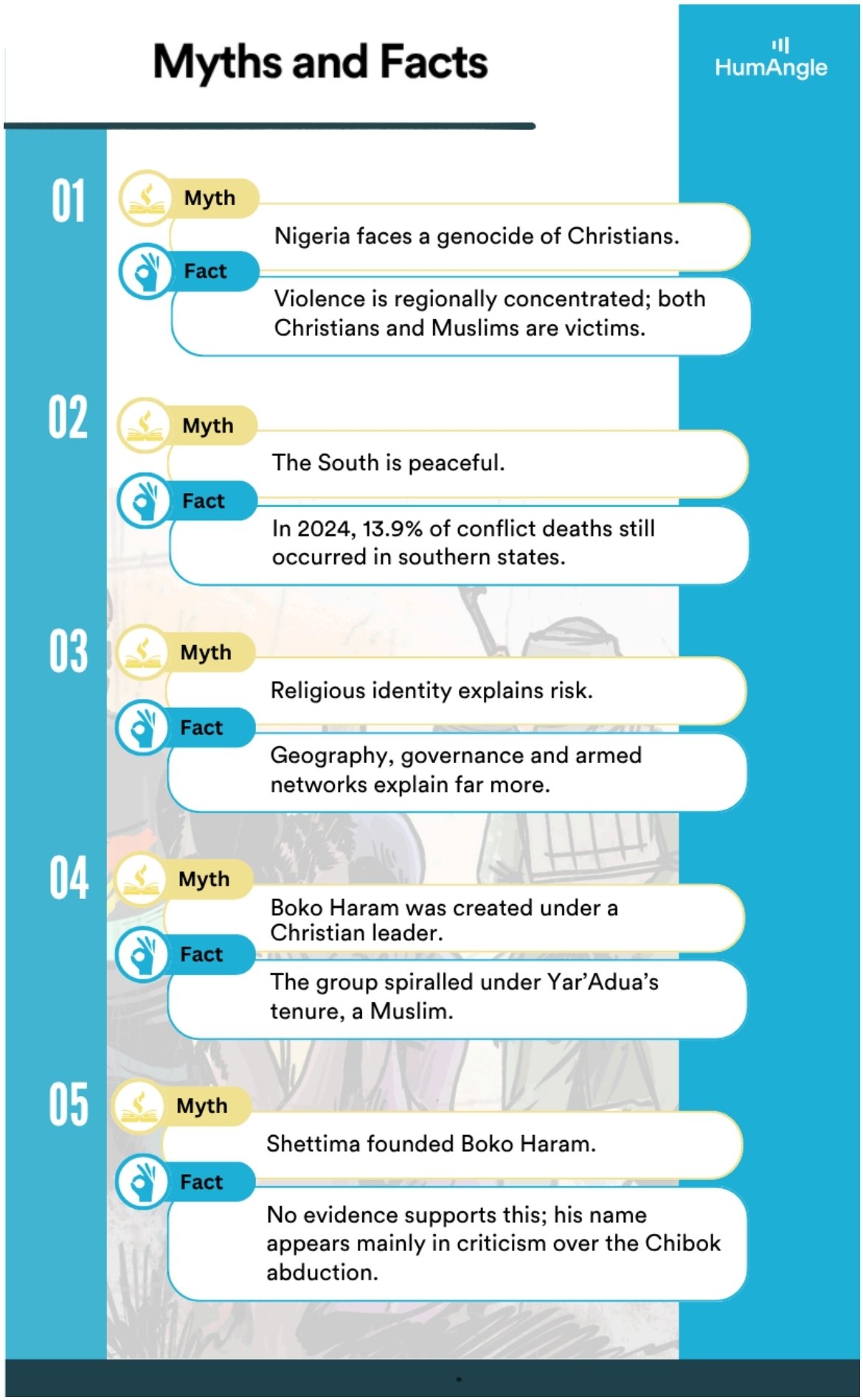

It helps to look at some of the particular myths or misconceptions people who believe in a Christian genocide tend to accept: the idea that Boko Haram emerged because Nigeria had a Christian leader is false. The Boko Haram insurgency actually began during the tenure of the late President Umaru Yar’Adua, a Muslim.

Advertisement

Also, there is no evidence to support the claim that Kashim Shettima, Nigeria’s Vice-President and former governor of Borno state, is one of the founders of Boko Haram. The burden he continues to bear stems from his alleged poor handling of the Chibok schoolgirls abduction and his inclination to a non-kinetic approach over a kinetic one during his time as governor.

Conflicts over politics, ethnicity, and resources often precede religion as a cause of violence in Nigeria. Communities assumed to profess one faith have experienced internal crises among their members over resource control, as have others with multi-faith and ethnicities across the country.

Advertisement

The most compelling argument against labelling the crisis as ‘Christian genocide’ is that it impacts both Muslims and Christians. Conflicts over land, power, and resources often take on a religious dimension based on the parties involved.

Previously, HumAngle debunked other claims suggesting Boko Haram planned to attack and take over the South East – stories that date back to the MASSOB (Movement for the Actualisation of the Sovereign State of Biafra) era.

Advertisement

MASSOB had used the idea to validate its cause and rally sectarian support.

Allegations of mass conversions of Christians to Islam or the burning of Christian bus passengers are among the falsehoods promoted.

Past HumAngle reports in August and November 2020 address these narratives in detail.

In the North East, Boko Haram has beheaded hundreds of Muslims for allegedly spying and collaborating with security forces. Several prominent Muslim clerics, including Sheikh Jafar Mahmud, Sheikh Ibrahim Gomari, and Sheikh Muhammad Auwal Albani, were targeted. In one incident, Sheikh Albani’s vehicle was riddled with bullets, resulting in his death as well as his wife and son. Several other Muslim clerics were assassinated across the region by suspected Boko Haram assailants for opposing their corrosive doctrine that promotes violence against anyone who opposes their brand of Islam, whether Christian or Muslim.

Mosque bombings, including the one condemned by the World Council of Churches in 2014, and massacres across northern Nigeria are too numerous to count.

HumAngle’s investigation (part one and part two) into the nuances of conflict in Nigeria’s Middle Belt, where both Muslims and Christians often frame violence through religious lenses, is particularly instructive.

In the north-west and south-east, violence is mischaracterised as mere banditry or actions of unknown gunmen. Terrorists and armed separatists kill, rape, abduct, and restrict access to farms and markets, often targeting people of their ethnicity and faith, revealing deep moral decay and distorted narratives of victimhood and resistance.

Where the violence hits hardest

States such as Borno (2,143 deaths), Zamfara (1,347), Katsina (1,306), and Kaduna (813) top ACLED’s 2024 fatality table, with Benue, Niger, Sokoto, and Plateau following closely. The epicentres correspond to zones dominated by jihadist insurgency, banditry, and communal conflict — three overlapping crises that leave little room for sectarian simplification.

The Nigerian Security Tracker, before it was discontinued, maintained data comparing attacks on churches and mosques. The figures did not support any one-sided persecution narrative. A revisit of those numbers could again help demonstrate that victims cut across faiths.

The evidence suggests that, because most victims live in majority-Muslim states, many are likely Muslim themselves, even as both faith communities face lethal attacks.

As of early 2025, the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) reported that over 3.5 million Nigerians remain internally displaced. Around 2.3 to 2.38 million are in the north-east, while between 1.19 to 1.32 million are displaced across the north-west and north-central.

The displacement pattern is similar to the death map, with many people concentrated in the north, especially in places where Islamist terrorists or criminal terror groups are active. Displacement blurs the lines of faith in both regions, affecting both Christians and Muslims.

Nigeria’s decision not to include religion or ethnicity in recent censuses, probably to avoid inflaming tensions, also made it harder to determine the religious composition of the most affected communities. This gap complicates efforts to claim or disprove religious targeting at scale.

When religion is the target — and when it isn’t

Religious targeting exists, but it is far smaller in scope than rhetoric often implies. ACLED’s analysis, between January and June 2022, found that only about 5 per cent of civilian-targeting events explicitly cited religious identity, mostly anti-Christian incidents.

Meanwhile, Muslims are not spared. In August 2025, for instance, armed assailants attacked a mosque in Katsina state during morning prayers, killing worshippers — a reminder that no faith community holds a monopoly on victimhood.

When Governor Charles Soludo of Anambra state recently rejected claims that “Fulani herders” were behind killings in south-east Nigeria, his statement challenged a deeply entrenched and dangerous stereotype. “Those who did the killings are criminals, not Fulani herdsmen,” he said, warning against the perils of false accusations that inflame divisions.

This narrative has at times spurred violent reprisals, such as in 2023 when residents of Anka, an entirely Muslim population in Zamfara state, north-west Nigeria, blocked a highway to protest insecurity and torched displacement camps populated mainly by Fulani people. “We host and accommodate the innocent Fulanis in Anka town, but their relatives did not stop killing and kidnapping us,” one of the protesters told HumAngle, encapsulating the tragic cycle of collective blame and retaliation.

Evidently, faith offers no shield from bullets or hunger, and geography grants no mercy from grief. Nigeria’s violence spares no one — Christians, Muslims, and nonreligious groups. The protracted violence demands better policy, deeper empathy, and accurate data.

School abductions: Terror without distinction

From Kankara in 2020 to Kuriga in 2024, mass kidnappings have scarred classrooms across the North. In Kuriga, 287 pupils were abducted and later freed after a harrowing ordeal. These crimes are primarily economic enterprises, not faith-based campaigns.

In July 2021, when 121 students were abducted from Bethel Baptist High School, located in Maraban Rido, Chikun Local Government Area of Kaduna state, in the country’s North West, aggrieved parents reportedly chased away government officials who had come to express sympathy, angered by what they saw as the government’s poor handling of the situation.

Gender violence: The silent epidemic

While the abductions often appear indiscriminate, their consequences expose deeper patterns of vulnerability, especially for girls, whose education and safety are frequently the first casualties of conflict.

Conflict zones in the North East and North West record a steady rise in gender-based violence (GBV): rape, early marriage, and domestic abuse. The kidnappings of schoolgirls in Nigeria, like the Chibok in 2014 and Jangebe in 2021, show that this violence stems from the state’s failure to protect citizens and not religion.

In Chibok, Boko Haram abducted 276 girls, most of whom were Christian, but some were Muslim. They said the attack was a rejection of “Western” education, which resulted in forced conversions, rape, and marriages. If the Chibok girls were targeted because they were mostly Christians, a terrorist group in the North West abducted 279 Muslim schoolgirls in Jangebe, showing how criminals use the same tactics as insurgents to stop girls from going to school.

ISWAP’s abduction of Dapchi schoolgirls in 2018 and its decision to hold back a lone Christian student, Leah Sharibu, for refusing to renounce her faith, laid bare the extremist ideology driving the group and the weakness of Nigeria’s state response.

In that moment, it was not the government but the terrorists who determined the fate of citizens, a terrible example of how fragile state authority can become when confronted with ideological violence and impunity.

These abductions reveal a pattern where harmful beliefs and extremism use girls’ bodies as battlegrounds. This is not the norm, but it is common, and their gender and religious identities make them more vulnerable.

The state’s weak and inconsistent response, the inadequate rescue efforts, limited rehabilitation, and lack of punishment for those who committed the violence have normalised such acts, eroding trust and making people less likely to attend school.

These cases show how insecurity, patriarchy, and sectarian manipulation work together to make girls unsafe and take away their future.

Beyond the ‘genocide’ frame

The friction reflects more than semantics — it underscores how simplified religious narratives risk misreading the crisis. The data simply do not align with claims of a one-sided genocide. Instead, they point to a complex landscape of armed actors, weak governance, and overlapping conflicts.

Policies should emphasise protecting civilians where they are most at risk, particularly in northern Nigeria. Invest in local mediation across the Middle Belt, where land, herding, and identity disputes ignite easily. Expand survivor services for GBV survivors, abducted pupils, and displaced families. Avoid sectarian shortcuts that obscure the geography and logic of violence.

Why this matters

Accurate framing is not academic nitpicking; it shapes how aid is distributed, how diplomacy is pursued, and how Nigerians understand one another.

Faith does not protect anyone from bullets or hunger. Geography does not spare anyone from grief. Nigeria’s violence is no exception, and that truth demands better policy, better empathy, and better data.

Years of reporting by HumAngle, which includes fact-checks, investigations, and data analysis, consistently demonstrate that we cannot neatly box Nigeria’s insecurity as a religious war. Instead, the evidence, ranging from myth-busting features to conflict data analysis, underscores governance failures, economic desperation, and historical grievances.

Analysis of ‘targeting’ in Nigerian conflict data

Analysis of disaggregated data spanning from 2020 to 2024 presents more insights into the crisis. The data shows geography and communal ethnic crises determine violence more than most factors, and a systematic, nationwide religious genocide is not evident despite specific targeting incidents.

The ACLED conflict reporting data does not support the view of a clear, systematic, national genocide targeting Christians or any single religious group for the following reasons.

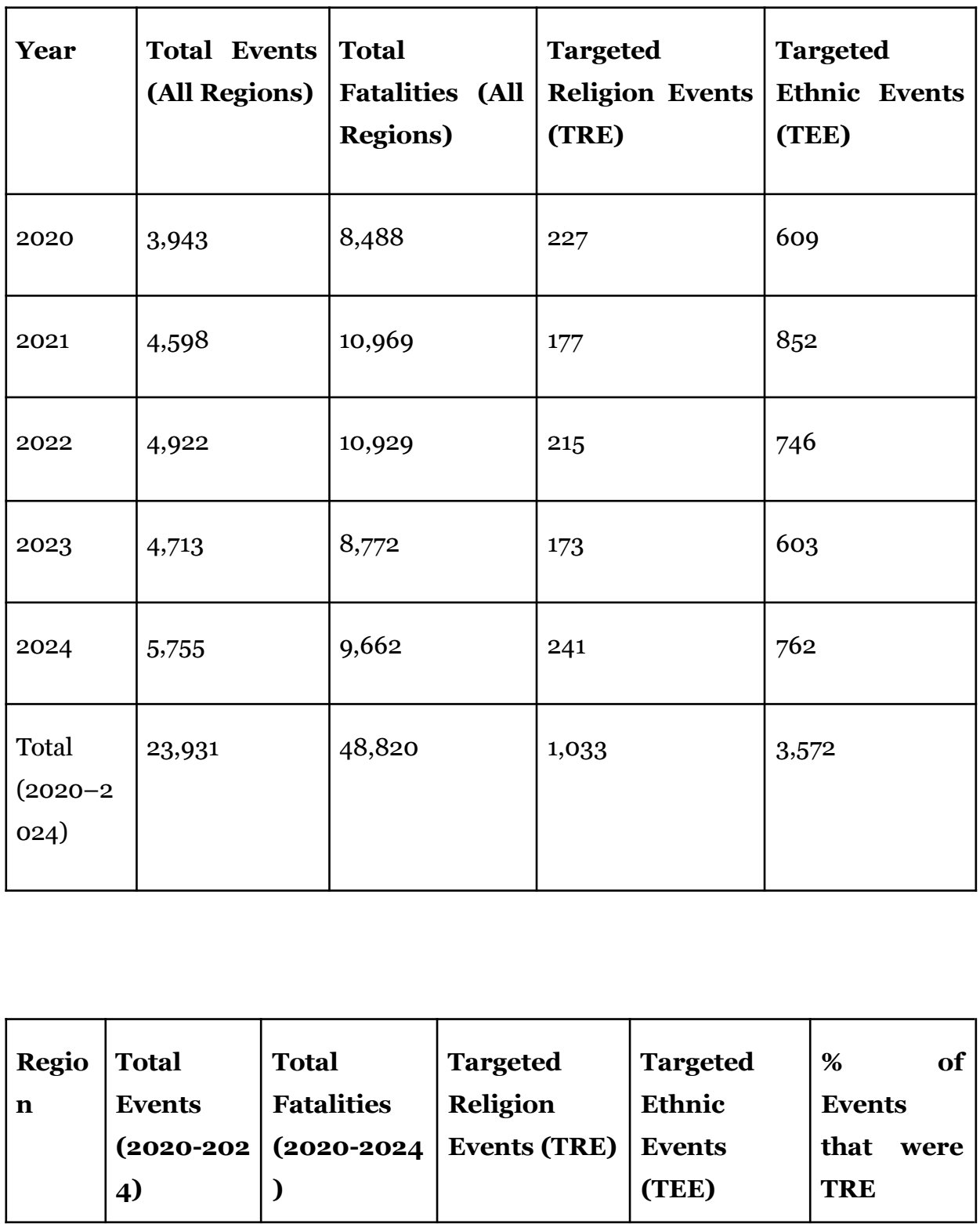

Analysis of five-year ACLED data indicates Nigeria faces a varied national crisis, with 23,931 recorded conflict events resulting in 48,820 fatalities between 2020 and 2024.

The majority of conflict-related deaths are concentrated in the north-east and north-west regions.

While incidents targeting religious groups occur, the data indicate these incidents are a small fraction of the overall conflict, accounting for approximately 4.3 per cent of all recorded events, and are far less frequent than ethnic targeting incidents. Factors such as the infrequency of religious targeting events, the dominance of ethnic/communal targeting in Nigerian conflict, and the lack of national concentration of target groups in the Nigerian conflict landscape are all evident in the data.

Across the five years (2020–2024), 1,033 total events were flagged as targeting a religious group. This is in contrast to the total of 23,931 conflict events.

Incidents involving ethnic targeting resulted in significantly higher fatalities than religious targeting incidents, with targeted ethnic events causing 4,990 fatalities between 2020 and 2024 compared to 779 fatalities from targeted religious events. This suggests that communal/ethnic friction, often related to land disputes or banditry, is a far more pervasive factor in explicit targeting than sectarian religious identity.

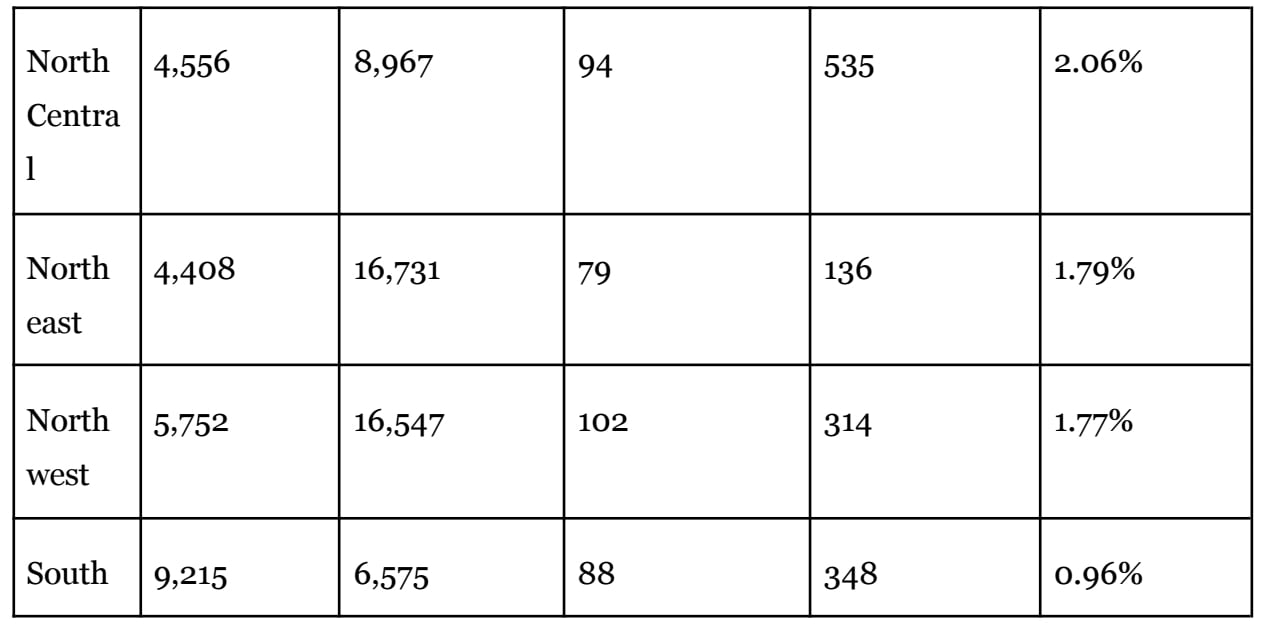

All four major regions (north-central, north-east, north-west, and south) host events targeting religious groups. Although specific regional attacks take place, no single region dominates the targeting metric as the north-east does in terms of overall fatalities.

For example, in 2022, the north-central region saw 16 targeted religious incidents, the North East experienced 16, the north-west saw 23, and the south saw 27, demonstrating a decentralised pattern.

Finally, the percentage of events in the data attributed to religious targeting puts things in perspective. In the north-central, only 2.06 per cent of events had religious motivation, and these include minute references like when an incident involves a church or mosque, even when they are not the direct targets. For the north-east, 1.79 per cent; for the north-west, 1.77 per cent; the southern region is 0.96 per cent, and so when compared to the national total, incidents targeting religion make up 4.3 per cent of all events.

North-east: Fatalities are primarily driven by insurgency, with top actors consistently including the Military Forces of Nigeria, Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), and Boko Haram.

North-west: High fatalities are linked to armed violence (banditry) and communal conflict, with top non-state actors being Communal Militias (Zamfara, Katsina, Kaduna), civilians, and Unidentified Armed Groups (UAG).

South: This region records the highest number of events but lower fatalities overall compared to northern regions, with primary actors being protesters, civilians, UAG, and police forces, indicating a dynamic often related to criminality, civil unrest, and law enforcement operations.

Additional data contribution by Mansir Mohammed