The date was May 29, 2012, when Lagos erupted into sudden student-led protests involving hundreds who blocked major roads, cordoned off the Third Mainland Bridge, and chanted “the name is our pride”.

Nigeria’s then-president Goodluck Jonathan had unilaterally renamed the prestigious University of Lagos after Moshood Abiola in a move widely perceived as political patronage overriding academic identity.

Public outrage was so high that the university, which had then existed for 50 years, was forced to suspend academic activities.

But this antecedent didn’t seem to have hindered successive leaderships from hijacking public-funded tertiary institutions as elements of validation and historical revisionism for transient politicians.

Advertisement

By 2018, Muhammadu Buhari’s administration would rename Ebonyi’s Federal University Ndufu-Alike after Alex Ekwueme, Nigeria’s first elected vice president who served from 1979 to 1983.

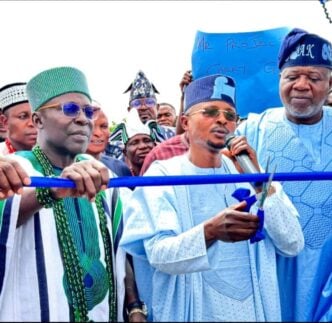

Nigeria’s incumbent president, Bola Tinubu, whose own name has now been painted over many existing public infrastructure, would rename the University of Abuja after the wartime military leader Yakubu Gowon and the University of Maiduguri after his now-deceased predecessor Muhammadu Buhari.

The official justifications for these have often been very contentious, lacking historical grounding, bypassing meritocratic standards, and politicising public academic spaces.

Advertisement

Despite Abiola’s then-growing posthumous recognition as an icon of Nigerian democracy, for instance, the late politician was not intrinsically linked to the University of Lagos.

The education ministry cited Buhari’s “strong commitment” to education, institutional reform, and national development. But the former president, whose records his successor admits will be debated, did not directly shape the University of Maiduguri’s founding in 1975.

Seyi Makinde, in 2025, renamed Polytechnic Ibadan after Victor Omololu Olunloyo, a politician who only served as Oyo state’s governor for three months in 1983.

Protests happened, and petitions often seek intervention and national critique, but these trends subsist.

Advertisement

The name changes, often decreed by executive fiat or legislative rubber-stamping, remain a troubling practice that undermines the identity and autonomy of public tertiary schools where political elites themselves rarely send their wards.

There’s the symbolic damage and selective amnesia that this causes.

A college established in the 1970s to drive agricultural innovation in a rural community carries with it a specific post-war or developmental ethos. To rename it after a political figure with little direct connection to its founding risks overwriting that history with transient politics.

University of Agriculture, Makurdi, was created in 1988 but renamed after late Benue politician Joseph Sarwuan Tarka after 31 years of its existence in 2019.

Advertisement

When leaders rename public institutions after themselves or their allies, it reflects a power structure more interested in legacy politics and self-aggrandisement than public service.

Nigeria is already grappling with an underfunded education sector, with only about 7.07% of public expenditure dedicated to it in 2025 as against the 15 to 20% benchmark for developing nations.

Advertisement

Tertiary education is severely constrained, leading to dilapidated facilities, under-provisioned labs, staff shortages, incessant strikes, and brain drain.

The cosmetic fix of renaming a tertiary school, by seemingly aloof politicians, becomes an easy headline that diverts attention from these pressing issues.

Advertisement

Damage from this renaming craze extends beyond symbolism.

Institutions with decades-long reputations, both locally and internationally, depend on the consistency of their identity. Their names become shorthand for quality, discipline, or regional speciality.

Advertisement

A sudden name change, university administrators explain, muddles research citation trails.

It polarises an institution’s web search reference terms in a way that diminishes its prestige and ranking, without the new name necessarily gaining cultural acceptance.

Google Trends data from 2018 to 2025 shows that public interest in the name “FUNAI” has outpaced interest in “Alex Ekwueme University”, even seven years after the renaming.

An institution can be saddled with an estimated hundreds of millions in financial burden, spending to recreate official document templates and communicate the renaming to international partners in the interest of its staff, students, and alumni members.

The renaming also burdens the institution with the political baggage, if the politician is controversial.

In many cases, like that of the University of Abuja, the public and the institutions themselves are not consulted prior. Decisions are made top-down, sometimes at the tail end of political tenures, as parting gestures to allies. This lack of participatory governance signals a complete disregard for public opinion.

It must stop. Institutions funded by collective wealth must be shielded from being made into items for personal glorification. Their names should reflect national heritage, not individual ego.

A reasonable way to honour a public figure would be to name projects after them, like faculty buildings, libraries, related research centres, think tanks, and scholarships. Not entirely overwrite existing schools.

Also, Nigeria is a country filled with unsung heroes in scientists, teachers, civil rights advocates, and cultural icons, many of whom are overlooked.

Elevating politicians to immortal status while sidelining these contributors suggests that political power, not public service or intellectual contribution, is the highest form of achievement in Nigeria.

Nigeria’s public institutions are paying the price for a few to erode historical truth and inflate political egos. Who will speak up?

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.