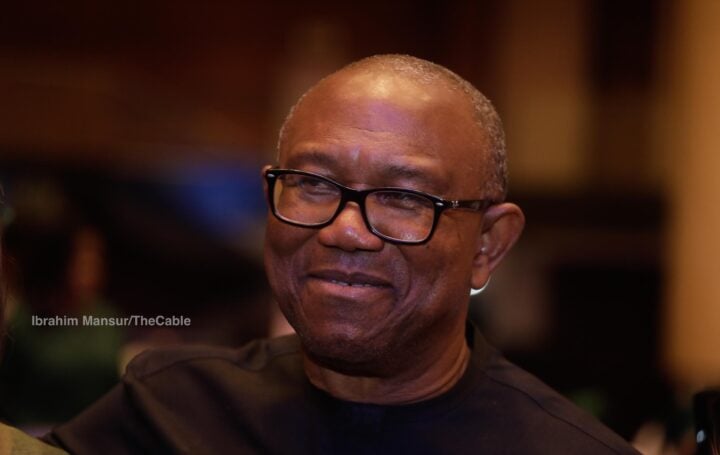

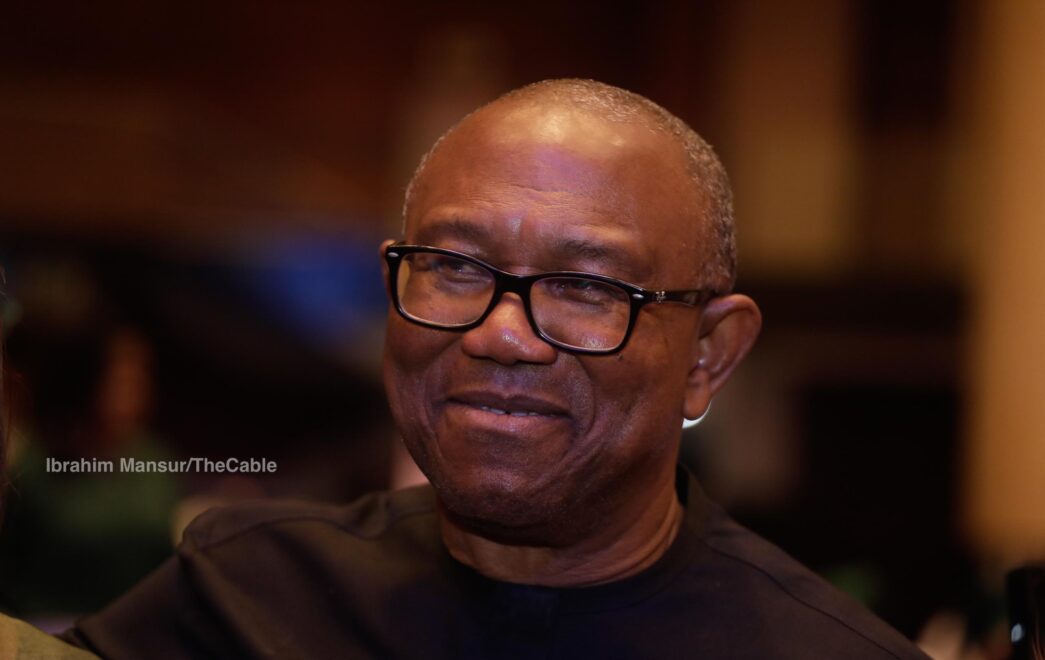

Peter Obi

BY BAYO OLUPOHUNDA

The decision of Peter Obi to initiate legal proceedings against the intrepid activist and lawyer Deji Adeyanju over a series of tweets targeted at the former 2023 Labour Party presidential candidate is brewing a storm about the thin line between criticism and defamation.

At the centre of this seething controversy are tweets in which Adeyanju accused Obi of being a mob leader, corrupt, bigoted, manipulative, dishonest, and in one particularly striking phrase, “a fraud parading himself as a messiah.” Obi’s legal team has since demanded that Adeyanju, in seven days, walk back his statements and tender a public apology in both national dailies and on social media, failing which they would seek damages for defamation. Adeyanju, however, has doubled down on his claims, insisting that he cannot wait to meet Obi in court.

The public spat between Obi and Adeyanju has created tension between his supporters and those sympathetic to Adeyanju. Particularly, it raises questions about the tension between free speech and a politician’s reputation, and also about the tolerance expected of public figures in the face of criticism and about how Nigeria’s political culture should handle the increasing online toxicity, which has increased since the 2023 elections

Advertisement

For Obi’s supporters, referred to as the Obidients, the matter between Adeyanju and their principal is simple. They argue that Adeyanju’s tweets crossed the line of legitimate political criticism into outright defamation. To them, calling a political figure like Obi corrupt, dishonest, or manipulative without offering concrete evidence is reputational sabotage. Obi, they argue, has every right to protect his name and to seek legal redress where his integrity is deliberately maligned.

Obidients also argue that failing to act against Adeyanju would amount to accepting falsehoods that may stick in the minds of Nigerians, especially at a time when political narratives and perceptions are shaped less by detailed policy arguments and more by soundbites, allegations, and trending hashtags.

On the other hand, Obi’s critics see things very differently. They argue that being a politician, especially one who aspires to be the president of Nigeria, necessarily means submitting to a torrent of criticism, mockery, and even insult. To sue over tweets, they argue, risks portraying Obi as thin-skinned, intolerant, and ill-suited to the rigours of leadership in a chaotic and divisive political landscape like Nigeria.

Advertisement

They point out that President Bola Tinubu, who was the target of countless insults, memes, and even conspiracy theories during and after the 2023 elections, has largely refrained from suing critics. They note that the Obidient movement itself has often been accused of hurling abuses at opponents, including the president, and that it would be inconsistent for Obi to demand immunity from harsh criticism while the horde of his online supporters engage in similar practices. Critics of Obi insist the lawsuit is frivolous. Adeyanju, in a television appearance on Channels TV on Friday, August 29, said Obi or any other politician should be open to criticism.

Comparatively, this blurred line between criticism and defamation is not unique to Nigeria. Globally, public figures are caught in a dilemma on how to respond to allegations and insults. A case that came to mind was the United States Supreme Court decision in New York Times v. Sullivan, which established that public figures must prove “actual malice” – that is, that false statements were made knowingly or with reckless disregard for the truth – before they can win a defamation case.

This very high bar for defamatory lawsuits reflects the principle that democratic discourse must be “uninhibited, robust, and wide-open,” even if it includes sharp attacks on those in power. For example, American politicians are routinely lampooned, ridiculed, and accused of incompetence or dishonesty, but lawsuits are rare, precisely because the law gives wide latitude to critics and places the burden on politicians to prove malicious intent.

In the United Kingdom and France, by contrast, defamation laws are somewhat more favourable to claimants, and public figures have occasionally pursued legal redress against what they perceive as damaging allegations. Yet even in both countries, lawsuits are fraught with risk. When former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson faced relentless media criticism and allegations of dishonesty during the Brexit debates, he refrained from suing, understanding that such actions might appear authoritarian.

Advertisement

French President Emmanuel Macron, likewise, has faced severe public insults – including graffiti and public demonstrations likening him to monarchs or tyrants – but his strategy has largely been to ignore or outlast the criticism rather than to sue. The calculation is usually that suing critics, unless the allegations are both very serious, like the Candice Owen-Macron case, and demonstrably false, only amplifies the original insult and paints the politician as intolerant of dissent.

In Nigeria, politicians have sometimes gone to court to defend their reputations. Peter Obi himself previously threatened legal action against Bayo Onanuga, a senior aide to President Tinubu, over remarks suggesting that Obi’s supporters were plotting to sponsor nationwide protests. He demanded a multi-billion-naira apology.

Similarly, governors and other senior officials have, in recent years, pursued defamation suits against journalists, bloggers, and activists. The legal terrain in Nigeria is such that defamation remains a recognised tort, and courts have on occasion awarded damages. Yet the pattern has also raised concerns that litigation is increasingly being used by influential individuals to silence critics. Lagos lawyer and human rights activist Femi Falana has also argued that defamation suits hinder free speech and discourage scrutiny of those in power.

The Obi–Adeyanju clash also raises a strategic question of provocation. Adeyanju is a seasoned activist and outspoken critic who thrives on public confrontations. By his own words, he “can’t wait to meet Obi in court,” implying that he welcomes the spotlight of a legal battle. For someone like Adeyanju, litigation could provide not just a platform to amplify his criticism but also a chance to frame himself as a political victim. It is possible, then, that Obi has walked into a trap by allowing himself to be goaded into potential litigation, where the drama of the proceedings may serve Adeyanju’s agenda. The activist has nothing to lose in terms of reputation; Obi, on the other hand, risks being seen as intolerant or authoritarian if he is perceived as trying to silence an opponent.

Advertisement

But there is also a case to be made that ignoring such provocations comes at a cost. In the era of viral tweets and algorithm-driven media, falsehoods and allegations can spread rapidly, shaping public opinion even if they are later proven to be untrue.

If a politician consistently allows damaging narratives to go unchallenged, the risk is that they solidify into common knowledge. A recent example is the Jibril of Sudan conspiracy theory, when the late President Buhari was said to be a clone from Sudan while he was alive. It is still surprising that many people believe the conspiracy theory pushed by the IPOB leader, Nnamdi Kanu, to be true.

Advertisement

For someone like Obi, whose political brand is closely tied to a polarising perception of integrity, any form of allegations – even if baseless – can be particularly damaging.

In this light, allowing Adeyanju’s tweets to circulate unchallenged might be seen as reckless, damaging his brand. Legal action, therefore, can be framed as not just self-protection but as a way of signalling seriousness about defending integrity.

Advertisement

However, the balance lies in distinguishing between ordinary political criticism and defamatory falsehoods. Saying that a politician is a bigot, a political prostitute or a leader of the mob or unfit for office may be harsh, but it is generally recognised as opinion – protected under free speech principles. But alleging that a politician profited from an investment scheme, diverted funds, engaged in bribery, or committed fraud without evidence may cross the line into actionable defamation.

Adeyanju’s statements arguably straddle this boundary, and Obi’s legal team may well succeed in court if they can demonstrate that the allegations are false and damaging. At the same time, public perception often matters more than legal verdicts. Even if Obi wins in court, he may lose in the court of public opinion if Nigerians see the lawsuit as an attempt to stifle dissent.

Advertisement

In comparison, politicians who endure criticism without recourse to the courts often emerge stronger, projecting resilience and tolerance. Barack Obama, during his presidency, faced birther conspiracies from President Donald Trump, who questioned his citizenship – a defamatory allegation by any standard. Yet Obama refused to sue, instead ridiculing the claims and eventually producing his birth certificate and shaming his detractors. The restraint reinforced his image as a leader who rose above petty attacks. Similarly, Nelson Mandela endured decades of vilification by his opponents but rarely pursued legal options.

In the end, the Obi–Adeyanju dispute highlights a fundamental tension in democratic politics: the right of public figures to defend their reputations versus the need for societies to protect vigorous, even unruly, debate about those who seek power.

Obi’s supporters are right to insist that no one should be free to spread malicious falsehoods without accountability- an accusation many have also accused Obidients of being guilty of. Adeyanju’s defenders are equally right to argue that politicians must develop thick skins and avoid weaponising defamation law to muzzle dissent. Whether Obi is vindicated or tarnished by this lawsuit may depend less on the technicalities of defamation law and more on public perception. Was he defending integrity, or was he proving intolerant of criticism? Was Adeyanju exposing a thin-skinned politician, or was he irresponsibly weaponising free speech to destroy reputations?

Obi faces a slippery test. If he is to remain a serious candidate for the presidency, he must project both integrity and tolerance. Adeyanju, on his part, as seen in his recent doubling down on national TV, may relish the confrontation, but his credibility will rest on whether he can prove his claims or whether he has merely mastered the art of provocation. In the end, if this case eventually gets to court, it will be a test of free speech and defamation and the mainstreaming of social media and how it is shaping political discourse.

Olupohunda tweets @bayoolupohunda

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.