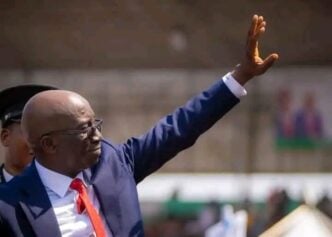

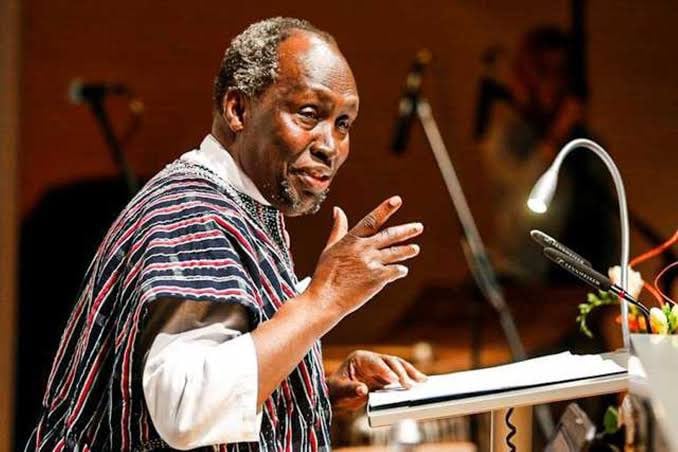

If there ever were a Mount Rushmore of African literature, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, who died on Wednesday at 87, would be one of the heads chiselled on it for eternal reverence.

Alongside names like Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Ayi Kwei Armah, and Flora Nwapa, Ngugi was a radical member of the continent’s first wave of writers who challenged colonialism and its unbridled racism. They were the first set of lions who learnt to write stories that countered the tales glorifying the hunters.

But Ngugi’s radicalism went a step further than that of his contemporaries. He believed true decolonisation can only be attained when writers write in their native languages. A notion he preached and practised for almost half a century. He published over 30 works, spanning novels, plays, and memoirs, and more than half of them were originally written in Gikuyu, his mother’s native language.

His disdain for English — the language of the colonisers, as he described it — strained his relationship with other African writers, particularly Achebe. It was also said that his language politics consistently cost him the Nobel Prize for Literature later in his life.

Advertisement

Colonialists and their language were not the only antagonists Ngugi incurred in his lifetime: he also wrote scathingly about the Kenyan ruling class. He was once arrested and detained for almost a year without trial for a play he co-wrote.

Ngugi’s irrepressible anti-colonial and social justice activism was deeply incited by his bloody childhood during the Mau Mau Rebellion in Kenya.

GROWING UP DURING THE MAU MAU REBELLION IN KENYA

Advertisement

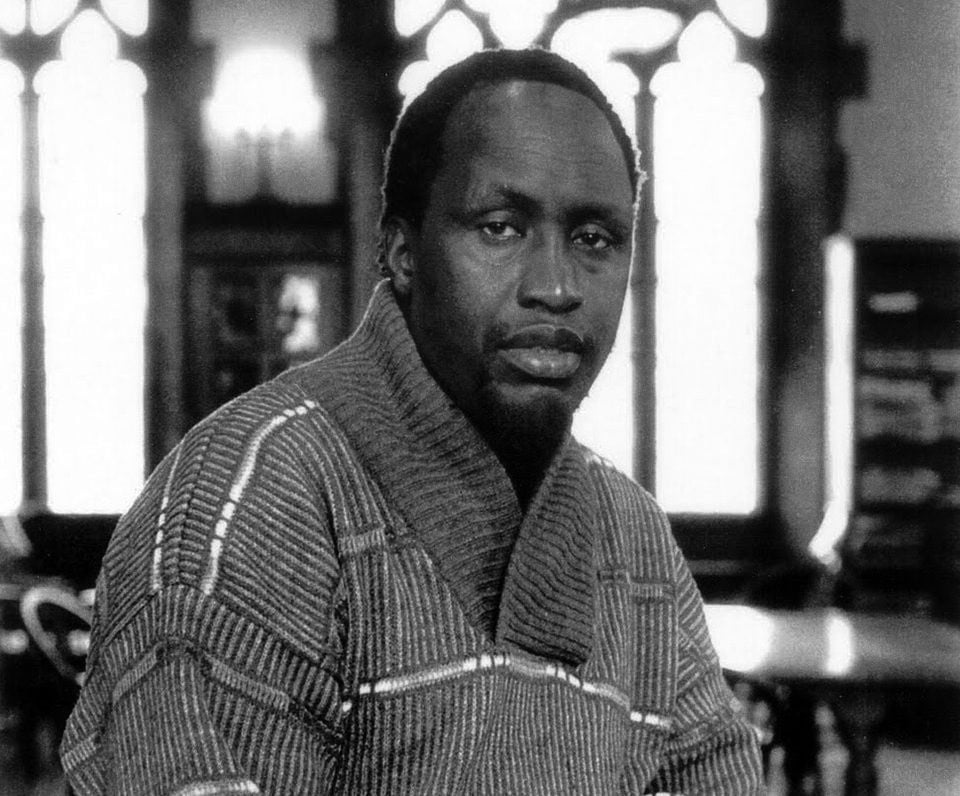

He was named James Thiong’o Ngũgĩ when he was born in 1938. He was raised in Limuru, in Kenya, which was under British colonial rule.

Ngugi’s father was an alcoholic who had multiple wives and 24 children. Ngugi’s mother, however, was determined to send her children to school.

“I have always wondered how a woman who could not read or write came to dream of school for me. She passed the dream of education on to me,” he told the New Statesman in an interview in 2021.

The family scraped Shillings together to send Ngugi to Alliance High School, a reputable boarding school in Kenya.

Advertisement

In the background, the escalating war between the British Army and the local rebels, known as the Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA), was underway. The bloodshed would culminate in the Mau Mau revolt, which lasted until 1960.

Ngugi’s family and those around them were affected by the unrest. Ngugi had brothers who fought on either side of the divide. One of his brothers was gunned down by a British soldier for not obeying his order. The brother, who was deaf and mute, had not heard the order.

One day, Ngugi returned from his school and saw that the colonial forces had ravaged his village. Houses demolished, farms burnt and everybody he knew displaced.

“I stop, put down the box, and look around me,” Ngugi wrote in the opening page of ‘In the House of the Interpreter’, a memoir published in 2012.

Advertisement

“The hedge of ashy leaves that we planted looks the same, but beyond it our homestead is a rubble of burnt dry mud, splinters of wood and grass.

“My mother’s hut and my brother’s house on stilts have been razed to the ground. My home, from where I set out for Alliance three months ago, is no more.”

Advertisement

These ordeals were the formative bedrock of Ngugi’s staunch anti-colonial views and writings. He had to escape to Uganda to complete his education at Makerere University.

CHINUA ACHEBE HELPED TO PUBLISH HIS FIRST MAJOR BOOK

Advertisement

It was at Makerere University that Ngugi met Achebe during the 1962 Conference of Writers of English Expression. The encounter would change Ngugi’s writing career and life forever.

Achebe was Africa’s most popular writer following the release of ‘Things Fall Apart’ in 1958. The Nigerian had achieved global success, a feat previously believed to elude African writers, and Ngugi needed Achebe’s input on the manuscript he was working on.

Advertisement

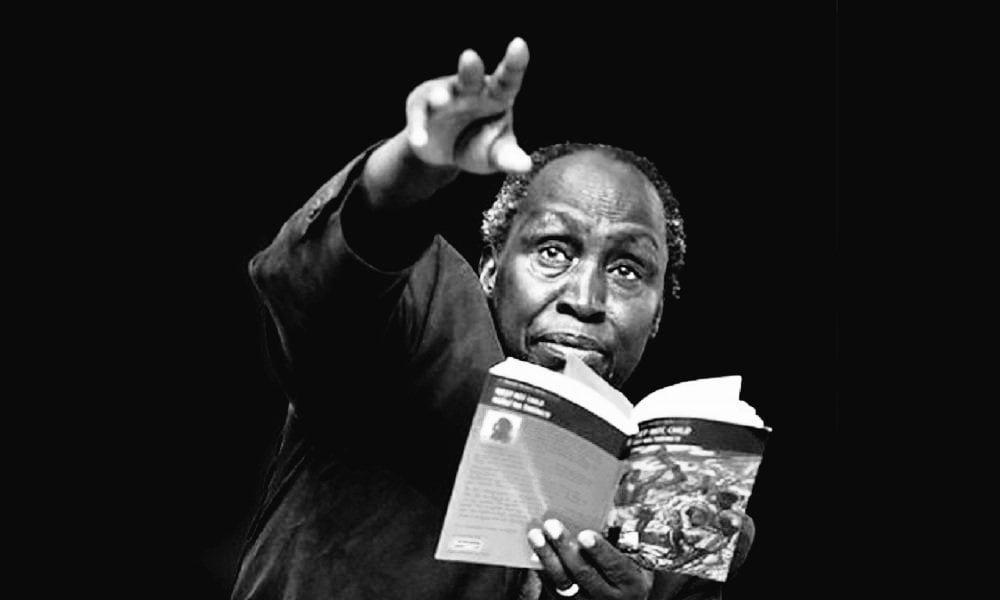

Ngugi shared the draft with Achebe, who not only graciously offered suggestions but also forwarded it to his publisher in the UK. The manuscript became ‘Weep Not, Child’, Ngugi’s major book, published in 1964.

The book was the first modern novel in English by an East African writer. A year later, Ngugi won a scholarship to the University of Leeds, where he earned an MA in literature.

FOUGHT COLONIALISM THROUGH BOOKS

‘Weep Not, Child’ set the tone for Ngugi’s attack on colonial rule and its residue on Kenya and other African countries at length. The book draws on Ngugi’s childhood experiences during the Mau Mau revolt and the damage inflicted on Kenyan families.

In ‘The River Between’, published in 1965, Ngugi resumes his interrogation of the Mau Mau rebellion and how Christianity, the religion of the colonialists, drove a wedge between two neighbouring Kenyan villages.

‘A Grain of Wheat’, published in 1967, is a deep psychological dissection into the mind of a Kenyan who betrayed his village’s Mau Mau hero to the British forces.

Ngugi then shifted his searing attention to the post-colonial ruling class in Kenya. ‘Petal of Blood’, published in 1977, is an interwoven tale of how the corruption in Kenya’s early independent days was a byproduct of the colonial structure.

Ngugi then co-authored Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), a stage play. The work was published in Gikuyu and served as a biting condemnation of Kenya’s post-independence leaders.

The use of the local language ensured that the people understood the play’s message well. The play’s popularity drew the government’s attention, and Ngugi was subsequently arrested.

The writer was detained for a year without trial.

WROTE A WHOLE BOOK ON TOILET PAPER IN PRISON

While in prison, Ngugi had no access to real writing material. Yet Ngugi chose to continue his writing, but with no papers to write on, he began scribbling on tissue paper.

When Ngugi left that prison in December 1978, he had the first draft of the manuscript that would become ‘Devil on the Cross’.

‘DECOLONISING THE MIND’ AND FEUD WITH ACHEBE

Around 1977, Ngugi, in an attempt to eschew all colonial influence, dropped his English birth name “James”.

He also discarded English as the primary language for his literature and pledged to write only in Gikuyu, his native tongue.

Ngugi’s pedagogy led to the publication of ‘Decolonising The Mind’. The work was a collection of essays on African language, culture and linguistic decolonisation.

Ngugi posited that only literary works written in an indigenous language can be classified as African literature. He added that Africans who write in English or French are just as guilty of propagating colonialism as those who colonised the continent with their language.

Achebe was against Ngugi’s argument. He pointed out the flawed logic in Ngugi’s position and argued that colonial language can be “Africanized” till they read more like an indigenous tongue than a borrowed one.

The intellectual face-off strained the relationship between the two acquaintances.

“Achebe said English was a gift. I disagreed,” Ngugi told The Guardian in 2023.

“But I wasn’t attacking him in a personal way, because I admired him as a person and as a writer, and what he was doing with his novels.

“I realised he was angry at me, because in the first edition of one of his books, he had quoted me at length, but in the second he removed me completely.”

Ngugi became a professor of comparative literature and English at the University of California, Irvine (UCI), in 2002 and taught there until his death.

He was married and divorced twice. He had nine children. Four of them are published authors.