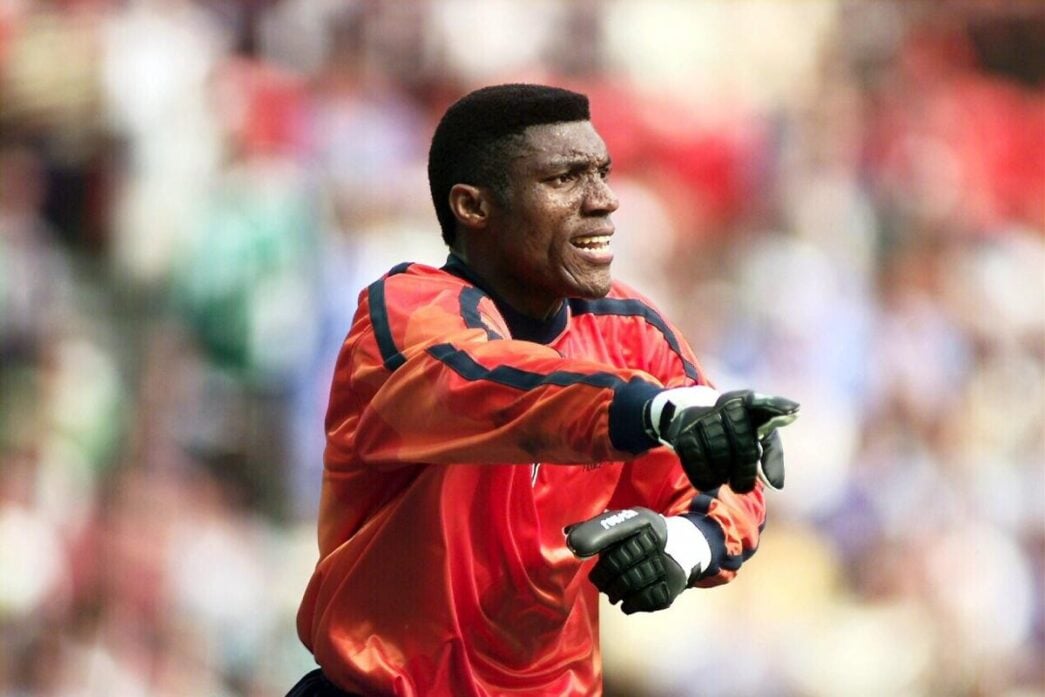

Peter Rufai was more than a goalkeeper. He was a myth, an inspirational picture on the wall for misty-eyed children. He was a tale by moonlight, and the retelling of his brilliance was almost a legendary fable. He was “Dodo Mayana”, a sight so pleasurable that one craves to see it again tomorrow and the next day.

He died on Thursday at 61, and to immortalise him, superlatives have poured unstintingly onto the pages of Nigerian newspapers.

The kids who watched Peter Rufai at his awe-inspiring best never wanted to be a goalkeeper; they wanted to be Peter Rufai. He brought beauty, eccentricity and colour to what was often considered the least interesting football position.

He would leap like a deranged cat to claw out shots travelling at an impossible pace. He danced, juggled and laughed in the face of danger while everyone was soiling themselves. With his signature punk hairstyle and freckled face, Rufai was fashion, flair, and fiery passion in one.

Advertisement

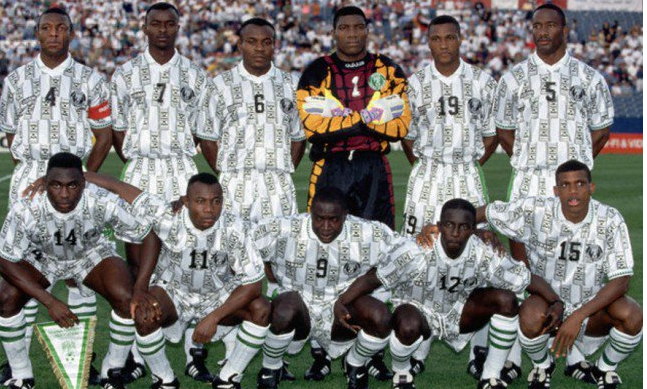

Rufai was the safe hands behind Nigeria’s golden football generation. He was the spine. He was the foundation upon which all the successes were built. His presence calmed Stephen Keshi into being the “Big Boss”. Rashidi Yekini’s goals would be mere consolations without his brilliant saves. Rufai’s acrobatics to deny Kenneth Malitoli and Kalusha Bwalya of Zambia in the 1994 AFCON final won Nigeria the trophy as much as Emmanuel Amuneke’s brace.

In turn, Nigerians were deeply enamoured of Rufai: fans once took to the streets to protest his exclusion from the national team squad. He was respected for his service: he captained Nigeria in the country’s first-ever World Cup appearance. Rufai was also a trailblazer: he was said to be the first Eagles goalkeeper to play professionally abroad.

Yet, all this greatness was a product of a decision made in haste, under duress and fear.

Advertisement

RENAMED DURING THE NIGERIAN CIVIL WAR TO CONCEAL HIS YORUBA HERITAGE

Peter Rufai was born on August 24, 1963, in Lagos. His father was the king of a community in the Idimu area of the state, while his mother hailed from Port Harcourt.

After a few years in Lagos, Rufai relocated to Kaduna in the northern part of Nigeria with his mother. It was at Community Primary School in Sabon-Gari, Kaduna, that Rufai discovered he loved football more than food.

“I used to join other kids to play football during break, and each time I would even forget that my mother gave me money for food. Different children will buy food and all, but my money will just be there in my pocket,” he said in an interview with The Popular Side.

Advertisement

“Not until my mother wanted to wash my uniform and she would see the money and asked why I didn’t buy food. I would tell her I forgot because I was playing football.”

Then the Nigerian civil war broke out in 1967, and Rufai’s mother was among the millions who thought it would be safer to return to their places of origin. They moved to Port Harcourt.

The war was between the Nigerian army and the Biafran separatist forces. The Nigerian military was predominantly composed of soldiers from northern or south-western Nigeria. The major ethnic group in Nigeria’s south-west is Yoruba, which is also the ethnicity of Rufai’s father.

Port Harcourt, where the mother relocated with the young Rufai, was under the control of Biafran soldiers. To protect her child from retaliatory attacks, Rufai’s mother dropped her son’s Yoruba name and gave him his famous first name, “Peter”.

Advertisement

In his new city, Rufai started at Municipal Primary School, where another hasty decision led him to become a goalkeeper.

The scoreline was 4-4 during an inter-school match, and Rufai’s teammates were frustrated at the team’s goalkeeper for conceding cheap goals. Rufai was a midfielder in the team.

Advertisement

The goalkeeper got angry and stormed out of the goalpost.

“He left the post, pulled off his shirt and threw it away. I caught the shirt, and I stepped into the goalpost,” Rufai recounted.

Advertisement

“I became the goalkeeper, and I was stopping the shots as the shots were coming. I was stopping with my head, legs and my whole body. So, we eventually won the match 5-4.

“At the next school match, everyone said I must be the goalkeeper. From there, I started playing as a goalkeeper.”

Advertisement

He became a household name in the community, and at just 11, he was selected for Rivers State’s U13 team to participate in a competition in Lagos.

At the competition, Rufai’s team was walloped in the semi-final by Bendel state. Rufai conceded nine goals.

Demoralised by the heavy defeat, a young Rufai nearly quit until he was spotted by a coach identified as “Tiger”.

The coach taught him the basics of positioning, anticipation, legwork, and other technical aspects that refined his raw talent.

Shortly after, Rufai moved to the Government Vocational School in Port Harcourt, where he trained to become an electrician.

At his new school’s playing ground, he was scouted by Sharks FC, formerly Rivers’ flagship football club, and was brought into their youth ranks.

At Sharks, he trained with Monday Sinclair, the legendary Nigerian football coach.

BEGAN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL AT 17

In the late 60s and early 70s, Stationery Stores FC of Lagos was one of the powerhouses of Nigerian football. The club had won consecutive Challenge Cups, now known as the Federation Cup, in 1967 and 1968. They had musicians like Sunny Ade and Salawa Abeni composing albums about their triumphs. The club also hosted a prestigious friendly match against Santos FC of Brazil in 1969 at the Onikan stadium, with the great Pele present.

Stationery Stores had a thrall around Nigeria’s exciting talents, and Rufai was not immune to the appeal.

Despite his association with Sharks FC, Rufai sneaked to Lagos for screening. He had finished his final school exam on that same day, and he journeyed to Lagos in a night bus. His mother was unaware of the travel plans. Rufai was only 17.

“I dropped my pen after doing my final exam, and I came to Lagos for screening with Stationery Stores, and I was selected,” in a chat with TV360 in 2014.

“I came to the screening with my Christmas shoes. No football boots. My parents never knew I was coming to Lagos for football, so I had only brought my dress shoes with me. I went into the goalpost with my shoes. Then captain of the team, Yomi Peters, told me ‘you’re selected’.”

A year later, he was the Stationery Stores goalkeeper in the 1980 FA Cup final against Bendel Insurance. The team lost by a lone goal.

Despite losing the final, the team represented Nigeria at the 1981 CAF Winners’ Cup after the continental football body banned Bendel Insurance.

At 18, Rufai was the wall behind players like Godwin Obiyan, Wakilu Oyenuga, Tarila Okorowanta, as Stationery Stores reached the continental cup’s final.

Rufai saved a penalty in the first match of the two-legged final against Union Douala of Cameroon that finished 0-0. The teenage goalkeeper suffered an injury in the return leg and had to be stretchered off. The team lost the match 2-1 and also lost the trophy.

FIRST EAGLES’ GOALKEEPER TO PLAY OVERSEAS

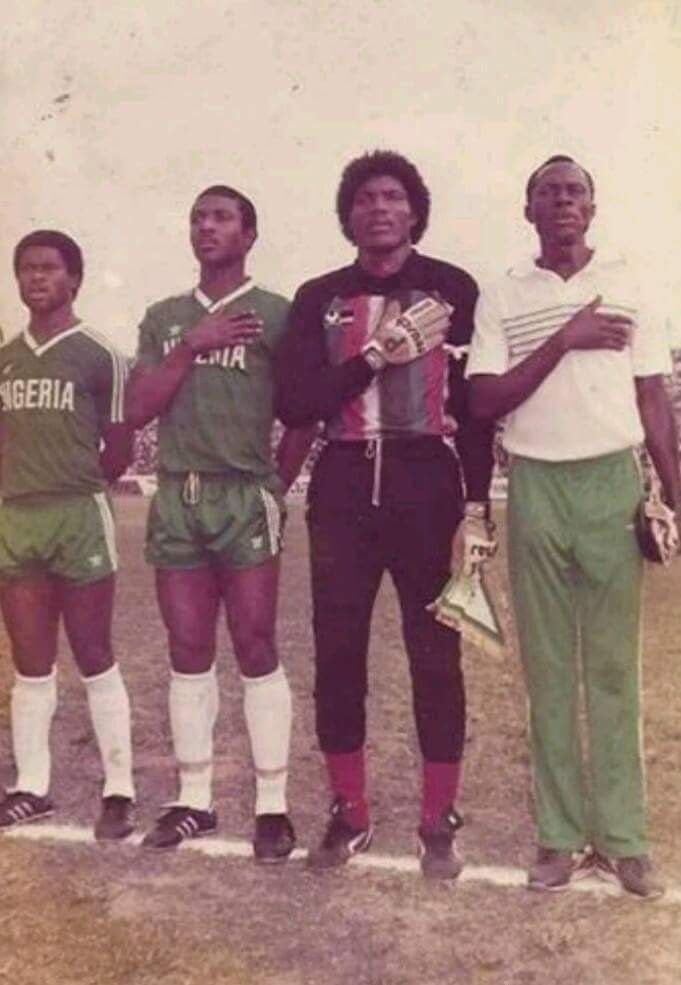

Rufai made his debut for the Green Eagles in a friendly match in December 1981. He featured for the national team at the 1984 African Cup of Nations.

In 1985, Rufai became the first-ever Nigerian goalkeeper to play abroad. He signed for Dragon FC of the Republic of Benin.

In a country that has produced legendary goalkeepers like Best Ogedengbe, Joseph Okala, Joseph Eriko, Peter Fregene, Rufai was the first of the lot to ply his trade professionally outside the country.

Rufai then moved to Belgium, where he spent six years with K.S.C. Lokeren Oost-Vlaanderen and K.S.K. Beveren.

SAFE HANDS BEHIND EAGLES’ GOLDEN GENERATION

The Super Eagles’ 1994-AFCON winning squad has often been hailed as the golden generation of Nigerian football. Rufai was the steady pair of hands behind the fritz of glitters.

At the competition in Tunisia, Rufai did not concede a goal until the semi-final against Côte d’Ivoire. In that game, he then saved Armani Yao’s kick during the penalty shootout, allowing Yekini to score the decider and send Nigeria to the final.

After the AFCON victory, Rufai and Clemens Westerhof, a former Super Eagles head coach, had a dispute, and the goalkeeper lost his number one spot in the team.

Six months later, he was reinstated to the top position with the captain band as a gesture of apology.

Rufai then captained Nigeria to the country’s debut at the World Cup in 1994. He was the man between the posts as the team won a group that had Argentina, Bulgaria and Greece.

He was also the team’s goalkeeper at the 1998 World Cup, after which he retired from the national team.

TURNED DOWN THE THRONE BECAUSE OF FOOTBALL CAREER

When Rufai’s father died in 1998, he was one of the candidates for the ancestral stool.

The goalkeeper was with Spain’s Deportivo La Coruna, and the club allowed him to return to Nigeria to discuss the throne succession plans.

However, Rufai turned down the crown and returned to Europe to continue his football career, which ended two years later.

HELPED TO DISCOVER NEW FOOTBALL TALENTS AFTER RETIREMENT

After retirement, Rufai stayed in his European base for years, continued to pursue further education, and worked as a sports administrator in Belgium and the Netherlands.

In 2003, he returned to Spain, settling in the country and opening a goalkeeper’s school.

Upon returning to Nigeria, he established a football development programme to discover and nurture young football talent across the country.

“After everything, I said I will dedicate my life to working with the youth after I have retired. In other words, thanking all Nigerians. And the only way I could thank them was to dedicate myself to the youth,” Rufai said.

Rufai’s oldest son, Senbaty, was a footballer who once played for Sunshine Stars in the Nigerian Premier Football League (NPFL).