[OBSERVER] From poor boy to accidental president

Nigeria’s leader has ridden out storms over corruption and a terrorist war. But as he stands for re-election, even with 2,000 feared dead from Boko Haram attacks, he remains a clear favourite

If the rise of Goodluck Jonathan from unknown zoology professor to president of Africa’s most populous nation was improbable, his bid for re-election may seem even more so.

Three multibillion-dollar government oil-corruption scandals, staggering PR gaffes and a wave of cold-blooded killings by Boko Haram Islamist militants still holding almost 300 schoolgirls after nine months would have toppled most presidents. That Nigeria’s accidental one is likely to live up to his name and sail through February’s poll is a testament to the complex mix of ethnic rivalry, patronage and intense competition for centralised oil wealth that underpins the country’s elections.

One week into the new year, Jonathan launched his campaign in the economic capital, Lagos, with the support of tens of thousands of cheering supporters decked in the red, white and green colours of his People’s Democratic party (PDP). As he addressed the crowd, a bloody rampage by Boko Haram was entering its fourth day in the remote north-eastern village of Baga. (The number feared dead from the attacks is now reported to be 2,000.) Some officials later put the toll at 2,000 dead. Yet the words “Boko Haram” were never mentioned in his speech.

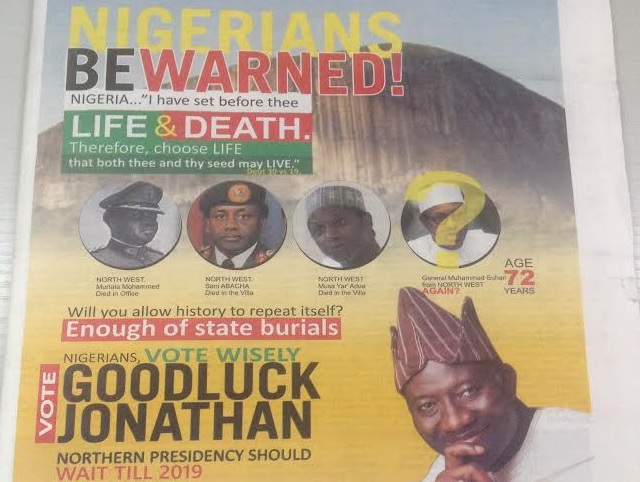

Advertisement

Such selectivity would be baffling almost anywhere else. But in many ways, it was in keeping with the national mood whereby most Nigerians see Boko Haram as a problem confined to the north-east and one jostling among many others that blight everyday life.

“I feel bad for our brothers and sisters in the north [where Boko Haram operates], but there are so many problems in Nigeria, and the system is so broken, that we can’t expect one man to work miracles,” said Vincent Ujuaga, a supporter waving a homemade party flag at the rally. “It’s not easy to be president and we must continue supporting him.”

Jonathan’s seeming indecision in the face of a major security crisis has thrown him into sharp contrast with his main rival Muhammadu Buhari, a military strongman whose 18 month regime was defined by its tough stance on corruption and insecurity. It took a surprise visit to Borno, the heartland of Boko Haram’s insurgency, almost two weeks after the Baga massacre before the president spoke on the issue. In response, a group of youth leaders headed by Hafsat Abiola, a prominent Nigerian human rights campaigner, wrote: “It’s not the first time you’ve met calamity with insouciance. Even you will remember the abduction of the schoolgirls in Chibok in April last year. It was 40 days before you addressed the country on that occasion. Break the silence, president.”

Advertisement

But Nigeria’s “our turn next” syndrome, an entrenched optimism that its day is coming, fuelled by handouts and Jonathan’s rags-to-riches story, means the incumbent is far from out of the race. Meanwhile, access to state coffers stuffed with petrodollars means he has the upper hand in a system of patronage. Around 70% of Nigeria’s 180 million citizens live on less than $1.25 a day.

To millions, Jonathan’s rise above the poverty that cripples Africa’s giant is the Nigerian Dream incarnate. Soft-spoken and often seemingly ill at ease with publicity, Goodluck Ebele Azikiwe was born to an impoverished family of canoe-makers in the remote district of Otuoke who scrimped to put him through school. A year later, oil was discovered in the mangrove creeks around hundreds of fishing villages such as Otuoke. The find would later devastate communities, fuelling corruption, wrecking the environment and breeding armed militancy and gangsterism on Nigeria’s southern shores.

“In my early days in school, I had no shoes, no school bags. There were days I had only one meal… I walked miles and crossed rivers to school every day. Didn’t have power, didn’t have generators, studied with lanterns, but I never despaired. Fellow Nigerians, if I could make it, you, too, can make it!” he said when he was elected in 2011 on a wave of optimism.

Yet Jonathan almost didn’t make it.

Advertisement

“Usually success is driven by fierce ambition, but I don’t think Jonathan particularly set out to be a deputy state governor, then governor, then vice-president and eventually president,” said Antony Goldman, head of Nigeria-focused PM Consulting. “His career is pretty remarkable, especially given how very greasy Nigeria’s political pole can be.”

The ascent began in 1999, when Jonathan was plucked from a job as an environmental officer for the Niger Delta Development Commission, one of the periodic flawed attempts to appease militants agitating for development by funnelling petrodollars to their leaders, to run as deputy state governor. “He didn’t want to run. He was more interested in consolidating peace, but he felt pressured when the vacancy came,” a former aide said. When a series of anti-corruption campaigns ensnared his boss, he was propelled up the ladder, eventually selected as deputy president by the ruling party.

Aides say kingmaker Olusegun Obasanjo, the former president whose two terms were marred by bitter power struggles with his own deputy, found Jonathan appealing because of his record as a loyal understudy for the state governor. When President Yar’Adua, a Muslim northerner, died in 2009, midway through his term, Jonathan inherited the top job and a growing insurgency in the north. But his standing for election in 2011 left many disgruntled, as it tore up an unwritten rule that the presidency should rotate between the Muslim-majority north and Christian-dominated south.

Still, he won the vote on a platform against corruption and thousands of cheering supporters welcomed “Uncle Jona” into office. “The problem was that the deals he had to make to get into office made it hard to make progress,” a party senator who helped run his campaign said.

Advertisement

A long-simmering insurgency in the south calmed down as one of their own took the helm. But Islamist militants in the Muslim north flared up, in part for reasons beyond Jonathan’s control.

Things soon unravelled further. In July 2012, a parliamentary probe revealed eye-popping corruption: $6.8bn (£4.5bn) petrodollars had been illegally drained from the nation’s coffers in three years. In one case, payments of $6.4m flowed from the state treasury within 24 hours to “unknown entities”. Another government investigation revealed corrupt, cut-price crude sales to oil companies that cost the treasury billions. Then a former central banker reported that up to $20bn had been diverted by the state oil firm over 18 months.

Advertisement

The scandals overshadowed progress elsewhere. Under Jonathan, the boldest reforms have been made to a crumbling power sector that means Nigerians rarely enjoy a full day of electricity. And hopeful steps have been made in restoring Nigeria’s once nationwide railway, abandoned as the elite turned to air travel. Many supporters see Jonathan’s biggest flaw as those around him. “He’s very good at listening and he tends to listen to everybody around him. Unfortunately, in Nigeria that’s a quality that doesn’t translate into good leadership,” a presidential aide said.

The level of sycophancy can be toe-curling: one adviser recently compared the president to Jesus. “People do not understand the burden this president is bearing. He’s like Jesus Christ. He’s bearing the burden of everybody,” Doyin Okupe said on a popular talkshow.

Advertisement

“When you go into government, the people you expect to ground you and advise you are the ones who start asking you to chop [steal] for them,” said Folarin Gbadebo-Smith, a former local government chairman in Lagos and director at the Lagos-based Centre for Public Policy.

“The Nigerian system was designed by colonialists to extract as much as possible and transfer it to a group that isn’t the commonwealth. From time to time, that group changes – first it was colonial masters, then the military, then a select group of citizens. So from that point of view, the government is functioning as it should be.”

Advertisement

There are glimmers that a disenfranchised electorate may be slowly waking up. When Jonathan’s entourage swept into Lagos this month, shutting down traffic for several hours, former card-carrying party member Anne Owoleo refused to visit the rally. “I really don’t have the time to hear what he has to say. If you’re in Lagos anytime he comes, the roads are closed for hours and the traffic is terrible. Someone who already makes our lives very hard, then our business is ruined for the day,” said Owoleo, who earns £10 a day with her mobile pharmacy.

“I feel used. We’re the ones that voted him into power but he’s just allowing those around him to embezzle while us ordinary people are suffering.”

THE JONATHAN FILE

Born 20 November 1957 Goodluck Ebele Azikiwe to an impoverished family of canoe-makers in the oil-rich Niger delta. He and his family scraped together to fund his education and he earned a PhD in zoology at the University of Port Harcourt. He is married to Patience Faka, whose outspokenness periodically lands both her and her husband in hot water.

Best of times Lifeblood of the economy before the 1970s oil boom, agriculture has been given a shot to the arm under Jonathan. A corrupt fertiliser subsidy has been cleaned up, meaning 70% of farmers now receive subsidy vouchers directly via their mobile phones.

Worst of times Under Jonathan, an inherited insurgency in the north has steadily advanced. The kidnapping of more than 300 schoolgirls by Boko Haram threw the international spotlight on the rebels, but also highlighted a bumbling government approach to the public.

He says “Four years is enough for anyone in power to make significant improvement, and if I can’t improve on power [electricity] within this period, it means I cannot do anything, even if I am there for the next four years.” Statement made while campaigning in February 2011. (Electricity remains a huge problem.)

They say: “There has not been any rise that’s been so meteoric in Nigeria.” Analyst Charles Dokubo.

5 comments

Mr President is clearly the right person for the job

@james. Jonathan is indeed the wrong person for the job. He is both physically and mentally incapable of leadership. He cannot comprehend simple situation and relies wholy on other to make judgement for him. Neverthless, he will win because of the sentiments across some parts of the country. The country remains the looser

Hmmm… Jonathan may seem to to TRIED and DONE his very BEST for Nigerians… Now, Nigerians, it seems, are TIRED and want Jonathan to be GONE and have a REST…

true talk, he need to go and take a sound rest.

I can’t understand why Jonathan is putting Nigeria through this. I voted for him the last time based on sentiments but he has performed below par. Am sorry but am not impressed with him as my president.