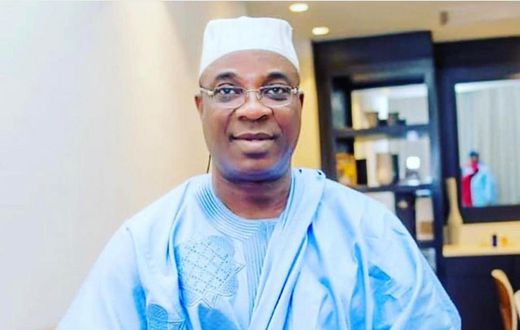

Today marks a month since Muhammadu Buhari left for the great beyond. The events of the last month have highlighted in obvious colours the vanity of life. I have also taken that time to ponder the legacy of one of Nigeria’s most consequential leaders. While revisionist history may never end, here is a brief account of who Buhari was.

In 2011, I was a budding campus journalist in my second year at the University of Ibadan. It was a time when I had just begun to find my own voice in writing. I had some sort of following on campus; when I wrote, people read and respected me for it. University management even made certain decisions based on the flow of my pen.

So, when I said Muhammadu Buhari and Tunde Bakare were my choice candidates for the 2011 elections, a few people took it seriously. I went from hostel to halls, faculty to classrooms, campaigning for the flagship candidates of the Congress for Progressive Change (CPC). What most people felt about Buhari and the hope he could bring to Nigerians in 2015, I felt it in 2010/2011.

On one occasion, it was reported that he was coming to Ibadan alongside Bakare to campaign at the defunct amusement park in Bodija. Guess who was there all afternoon? Yes, me. I campaigned thoroughly for this general, whom I believed was to become a changed democrat. On election day, when I voted for him, I took a picture of the ballot and posted it on Facebook, so proud of what I had done. Buhari won a few polling stations at the University of Ibadan, so when he lost the election to Goodluck Jonathan, I was sad, but proud of the decision I made and the efforts I put into that ballot.

Advertisement

While I would later meet Tunde Bakare on a few occasions in Nigeria and abroad, I never discussed my immense support for him and the general.

My 2015 switch

In 2014, I was on my way out of the university. This time, I had built, alongside my friend Samuel Osho, the most influential column on campus — we called it The Courtroom. I had won the Nigerian Championship of Public Speaking, helped restart the foremost public speaking event in the university to date — Jaw War — and had won the most influential journalism awards on campus. All this to say, my influence had grown, and my pen was now a lot more potent than it was in 2011. But I had switched sides.

I was one of those purists who were disappointed in Buhari for joining the All Progressives Congress (APC) and allegedly spending Bola Tinubu and Rotimi Amaechi’s money to drive one of the most expensive campaigns in Nigerian history. I had also come to a better understanding of the Buhari Acts of 1984, and I did not think he was the right man for Nigeria. So I campaigned against him and stuck with Jonathan. At the time, I wrote an article titled “The Seven Sins of Buhari” or something like that. It went viral in school, but many people thought I was joking, considering how much I rooted for Buhari in 2011.

Advertisement

This time, Buhari won.

He finally made history and did it in style, with a whole lot of goodwill. At this time, I had started working for TheCable. So I reported how the stock market was breaking old records and setting new ones because the new Sheriff was in town.

Budget padding and other sad stories

We all know how Buhari earned the name Baba Go Slow for not naming ministers for half of his first year as president. How, after naming ministers, he went against the advice of his minister of state for petroleum, Ibe Kachikwu, who had said the NNPC-run refineries should be sold. It’s been 10 years since then, and Nigeria is still funnelling funds into refineries that won’t work, only to come to the same conclusions.

In 2016, Buhari presented a budget to the national assembly, and for the first time in our democracy, the budget went “missing.” By the time it was found, it had been bloated with new insertions in what became known as budget padding. As an eagle-eyed journalist, I worked day and night to deliver a story to show the new insertions in the budget.

Advertisement

On the night of May 23, 2014, our newsroom got a call from the presidency that we had reported false news and were in the mischievous business of misleading the nation. Presidential aides sent emails and calls to my bosses asking that we take down the story, which they claimed had no basis.

Sadly, my evidence, which was from the budget office, had been taken down from the budget office website. However, with the use of OSINT tools, we were able to retrieve the evidence and tell the Buhari presidency that we stand by our stories. As we all know in hindsight, budget padding became official and has become a key part of the Nigerian legislative life.

After Buhari won, the economy showed signs of strength, naira stronger, stock exchange saw inflows, our current account became healthier, so you would expect an excellent economy. Not with Buhari, as he admitted, he was always unlucky with oil prices. So bad policies — or no policies– coupled with crashing oil prices, led Nigeria to our worst recession in 29 years. As former president Olusegun Obasanjo famously stated, the economy was not his strong suit.

Many sad stories here, but I can’t help but remember that Buhari appointed dead people. Unprecedented.

Advertisement

Enter Lazy Nigerian Youth

In 2018, at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meetings in Westminster, UK, I was fortunate to be the only Nigerian journalist in the room where Buhari spoke so badly about our youths. His exact words were that alot of us wanted to “sit and do nothing” because of oil money. I reported the story as professionally as I could, and Nigerians took it up, and it became the Lazy Nigerian Youth revolt.

Femi Adesina released a statement where he called me a “mischief maker” — I was already used to that slur. When we released the video of what Buhari said, I was vindicated.

Advertisement

One of the biggest news organisations in the world reached out to me to come speak to a global audience about the meetings and what my president said. I declined, I may have issues with my president, but it’s an internal, home-handled issue.

About five weeks later, the same Buhari signed the Not Too Young To Run Bill into law, opening the gates for many young people to run for office. The irony.

Advertisement

The man Nnamdi Kanu and Sunday Igboho wanted dead

By 2019, Nnamdi Kanu of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) kept driving the narrative that Buhari was dead and had been replaced by Jibril of Sudan. I debunked this and flagged it with Facebook. Kanu was so livid, he came online and asked his minions to find me and deal with me (I’m using less fruity language here). It was a tough couple of months for me.

Fortunately, Facebook listened and took down Kanu’s account for the threats and hate he was spreading.

Advertisement

In 2021, it was Sunday Igboho of the Yoruba Nation. Buhari’s government were seemingly after Sunday Igboho, who wanted the creation of a Yoruba state. Igboho fled Nigeria and was apprehended in Cotonou, Benin Republic. I was in Cotonou to report that too. For some reason, his supporters believed I was against them and attacked me, with the usual threats to kill me. I was saved by a cleric.

Only after Buhari’s death did Tunde Bakare, Buhari’s CPC running mate and friend, inform us that Buhari said he knew nothing about the situation. Another familiar note in Buhari’s music — he lets things happen with his authority, but without his say-so.

What is Buhari’s legacy?

I could go on and on about Buhari and speak of all the times we were in the same room in Westminster, Brussels or New York, but none of that will capture his legacy, which is one of the hardest pictures to paint.

To many, he was the messiah who could never be wrong. When things go south, they blame the people around him, but never St. Muhammadu. When things go right, they scream Sai Baba, Sai Buhari. To others, he is the worst disaster in the history of governance in Nigeria.

Let’s not join the emotional wagons; let’s stick to the facts. Here are some facts for you: Buhari led Nigeria into three recessions as military head of state and democratic president — that’s a record none of Nigeria’s leaders have ever attempted. The man also built the biggest social investment programme in Africa while watching Nigeria become the poverty capital of the world. Let’s not discuss the implications of devaluing the naira from 197 to a dollar, or shaving GDP per capita by about $500 per head.

Buhari holds the record as Nigeria’s longest-serving minister of petroleum, serving for 10 years. He opposed the removal of fuel subsidy for decades, including six of the eight years he was president. But the same man signed the Petroleum Industry Bill into law after more than 20 years of various government attempts to reform the industry.

He was voted on security, so did he secure Nigeria? Same pattern of answers. During his term, Boko Haram-related deaths dropped by as much as 92% and he was also famous for “technically defeating” the violent sect. On the other hand, kidnapping for ransom became a booming industry. School abductions became so popular that they became just another headline.

Buhari’s legacy is like a chameleon’s skin, it’s ever-shifting depending on the eye that beholds it. Search for light, and you’ll find glimmers worth praising; seek the shadows, and they will meet you halfway.

So when next they ask you in a year or 10, what is Buhari’s legacy? Your answer could be as simple as: it is the chameleon’s skin.

You can reach ‘Mayowa on Twitter @OluwamayowaTJ