In September 1887, Harry Johnston, acting consul of the Oil Rivers Protectorate (Niger Delta), procured the arrest in the wharfs of the Niger Delta of King Jaja of Opobo on the rather dubious charge of “obstruction of trade”. It accused King Jaja of violating a trade treaty with the British, which did not, however, have any penal provisions. The previous year, a Royal Charter granted in the name of Queen Victoria had placed the territory under the rule of the Royal Niger Company (RNC), which empowered it to “undertake and carry on the government or administration of any territories, districts, or places in Africa….” Essentially, the company was the government.

After arresting him, the RNC shipped King Jaja for trial over one thousand kilometres away to Accra, the capital of what is today known as Ghana. The day before the beginning of his trial in November 1887, the company notified King Jaja that he would stand trial in what was effectively a court-martial. Rear-Admiral Walter Hunt Grubbe of the Royal Navy presided. The notice was so short, King Jaja could not call any witnesses in his defence. Historian Elvar Ingimundarsson, who researched the history of the RNC, called it “a Kangaroo court.” It found King Jaja guilty and sentenced him to exile, from which he did not return alive.

Thirteen years later, the RNC lost its Royal Charter and Her Majesty’s Government took over direct administration of the territory that would later become Nigeria. It comprised a colony in Lagos and two protectorates, one to the north and the other in the south of the country.

On the 108th anniversary of the show trial of King Jaja in a Kangaroo court, the regime of General Sani Abacha re-enacted a similar script, leading to the execution on November 10, 1995, of Ken Saro-Wiwa, Saturday Dorbee, Nordu Eawo, Daniel Gbooko, Paul Levura, Felix Nuate, Baribor Bera, Barinem Kiobel, and John Kpuinene, together known today as the “Ogoni Nine”. Their crime was advocacy for the responsible exploitation of the hydrocarbons in their communities in Ogoni-land. Unable to call witnesses in their defence, their fate was pre-determined before a tribunal headed by Ibrahim Auta, a kinsman of Alhaji Abacha Maiduguri, who was the father of General Abacha. Like King Jaja, they were not allowed any right of appeal.

Advertisement

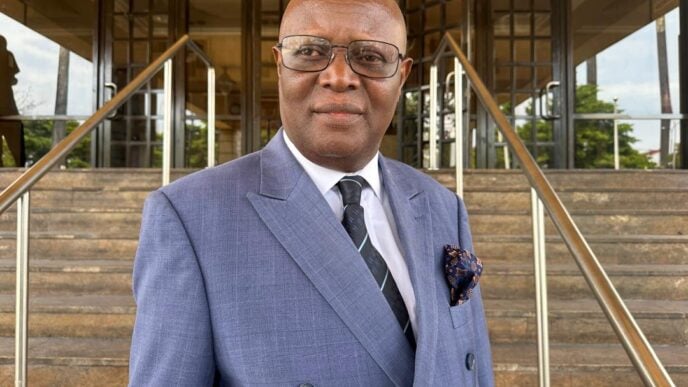

On October 12, 2025, the presidency announced that the Ogoni Nine were among 175 persons “who (had) received President Tinubu’s mercy.” The announcement followed a meeting of the National Council of State at which the honourable attorney-general of the federation (HAGF), Lateef Fagbemi, a Prince of the Offa Kingdom in Kwara state, who chairs the committee on the prerogative of mercy, reportedly presented the proposal to grant them pardon.

While the Ogoni Nine were included among the beneficiaries of the president’s mercy, King Jaja was excluded. Some would think that it is because the injustice he suffered happened so long ago that the reach of the president’s forgiving memory could not be expected to travel that far back in time. However, the list included Herbert Macaulay, the pioneer surveyor and nationalist, whose unfair conviction for theft occurred in 1913, a mere 26 years after the trial and exile of King Jaja. He was also a beneficiary of a posthumous pardon.

The pardon to Herbert Macaulay raises at least three significant issues. One is the scope and reach of the pardon powers of the president. Section 175(1) of Nigeria’s Constitution empowers the president to “grant any person concerned with or convicted of any offence created by an Act of the National Assembly a pardon, either free or subject to lawful conditions.”

Advertisement

The trial and conviction of Herbert Macaulay occurred in the Colony of Lagos in 1913. The Amalgamation of the Colony of Lagos with the Protectorates of Southern and Northern Nigeria, which created the territory now known as Nigeria, occurred the following year. Nigeria became a federation in 1951, 38 years after the trial of Herbert Macaulay. (How) was he convicted of a crime created by the national assembly?

Second, there is an implicit procedural requirement in the process of the prerogative of mercy: prior to making a recommendation, the committee should have had access to and reviewed the transcripts and records of the proceedings leading to the conviction in respect of which it chooses to recommend the exercise of the presidential prerogative. In the case of Herbert Macaulay, it appears that the committee did not even bother to have access to the records. This is not difficult to understand, given that the trial occurred so long ago. But it is a requirement.

Third, the purported pardon to Herbert Macaulay raises deeper issues about how best to immortalise and honour the heroes and sheroes of Nigeria’s colonial struggles. The presidency chose to pardon Herbert Macaulay in a list which, by its own admission, comprised almost exclusively of “Illegal miners, white-collar convicts, ….drug offenders, foreigners,….capital offenders.”

Ninety-three percent of the 175 beneficiaries of the prerogative of mercy announced by the president involved the most serious crimes known to law anywhere: 29.2% were traffickers in serious drugs, such as Cocaine. Another 1.8% were convicted for human trafficking; 24% were convicted for unlawful mining (itself the cause of insecurity in places like Zamfara State); 13.5% were murderers; 12:3% were convicted of looting the country and another 5.8% were convicted for the crime of hijacking. 4.6% were convicted for firearms and robbery respectively; and another 1.8% were convicted for kidnapping.

Advertisement

It is impossible to dream up a more squalid register of beneficiaries of the prerogative of mercy or a more criminally cynical exercise of presidential pardon. It is unthinkable that the government could persuade itself that the “labours of our heroes past” – among whose pantheon Herbert Macaulay is deservedly a doyen – are best honoured by festooning them with the company of drug-lords, murderers, kidnappers, gun-runners and human traffickers. It is entirely understandable that Herbert Macaulay’s descendants should feel scandalised by this.

It is no surprise that the publication of the list has been attended by credible allegations that certain insertions were oiled by generous inducements in the form of a quid pro quo. The list of beneficiaries is so seedy, it reads like a bazaar for mostly people in a position to purchase the pardon. Those who do not fit this description, such as Herbert Macaulay or Ogoni Nine appear to have been inserted to lend credibility to a seedy assemblage. It is a dreadful commentary on the Committee on the Prerogative of Mercy, the Presidency, and indeed the participants in the last meeting of the Council of State that they could reduce the institution of presidential pardon to this level of abuse.

In addition to the requirement that a presidential pardon is only available for crimes created by the national assembly, the constitution also imposes a procedural constraint on the presidential power of pardon. It is to be exercised after consultation with the National Council of State. The list was, therefore, only published after the Council of State meeting.

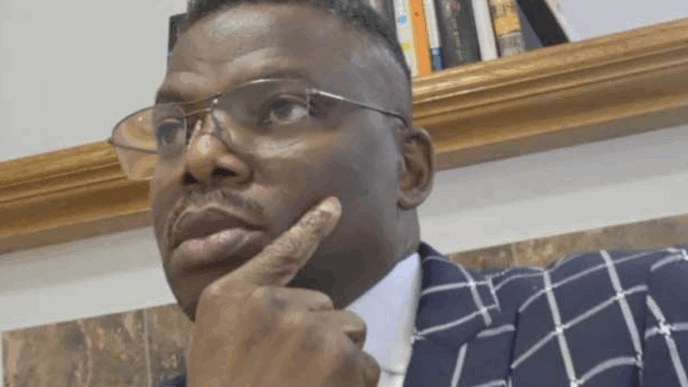

More than one week thereafter, the HAGF now claims, because of the scandal and stink unleashed by what they have done, that the list of beneficiaries is “still under review and has not been finalised.” The only reaction to this line is: pardon me?! The HAGF did not cite any law as empowering him to do this because there is none. Important and powerful as the office of HAGF is, he lacks any lawful powers to make these things up as he goes along in this way.

Advertisement

There is no way to diminish the damage that Lateef Fagbemi’s Committee on the Prerogative of Mercy has done to the presidential pardon. There are clear elements of illegality in what it has done and in what it proposes to do. It is seedy, and the immorality of it all plainly stinks.

Above all, the damage to national security cannot be quantified. Law enforcement and security agents will be reluctant to break a sweat in pursuit of serious offenders when they know that a president will cynically let the convicts loose to make prey of them. That is the ultimate crime in these presidential pardons. The biggest job a president does is to guarantee public safety and national security. In these pardons, President Tinubu retrenches and casualises both.

Advertisement

A lawyer and a teacher, Odinkalu can be reached at [email protected]

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.