BY LEKAN OLAYIWOLA

Nigeria still carries the world’s largest load of out-of-school children (about 10–12 million) with the north-west and north-central states accounting for a disproportionate share. Insecurity, climate change and politicisation are central drivers.

In a village on the Katsina–Niger border, the school year now runs on the weather. When rains fail and grazing thins, boys migrate with herds and men drift south for casual work; girls stay home to stretch food and care for younger siblings. The bell rings, but half the seats are empty.

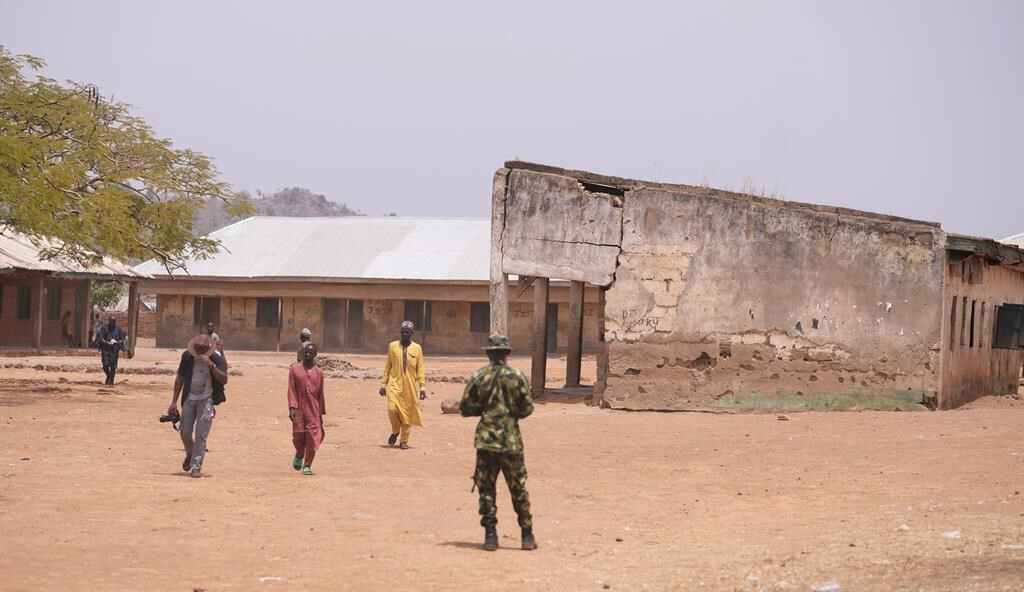

In Zamfara, a head teacher keeps two registers: one for students, one for kidnappings. Parents send children to school only if the road feels safe that morning.

Advertisement

In Jigawa, last year’s flood washed away a block of classrooms; the temporary tent has no blackboard. This is a system failure where governance gaps and climate shocks compound each other, and basic education becomes the first casualty.

The school system still expects yesterday’s climate.

In Katsina, Zamfara, and Jigawa, Sahelian climate stress has become a timetable rather than a forecast. Drought, desertification, and extreme weather are altering planting cycles and pushing seasonal migration. When households move, children’s attendance collapses. Yet education calendars, school feeding delivery, and assessment windows still assume stable residence.

Advertisement

National and global climate assessments have flagged northern Nigeria’s rising exposure to heat and water stress, pulling adolescents out of class for work, caregiving, or migration. But basic-education policy has not been re-timed for this new mobility. In plain terms,

Layered on climate change, banditry and abductions shut schools or make routes perilous; parents weigh risks and opt out; months become years. Post-attack withdrawals and long-term trauma keep children, especially girls, from returning. This creates a direct pipeline into early marriage, child labour, or recruitment by armed groups.

Three Institutional Chokepoints Where The System Breaks:

Politicised SUBEBs and weak last-mile execution: In conflict-impacted LGAs, school construction, rehabilitation, and teacher deployment are routinely delayed by counterpart-fund bottlenecks, contractor politics, or procurement disputes. UBEC can budget and announce; only SUBEBs and LGAs can site, build, staff, and secure.

Advertisement

Too often, projects chase photo-ops, not risk maps. The long trail of abandoned “almajiri schools” provides a cautionary tale in designing without local buy-in.

A security–education disconnect: Education in Emergencies (EiE) protocols which are temporary learning spaces, escorted transit and trauma support are patchily applied outside the north-east.

In the north-west, where banditry rather than insurgency dominates, the funding and coordination architecture is thinner, and school reopening decisions are ad hoc, resulting in long closures, no structured catch-up, and silent dropout.

Policies are designed for a sedentary child in a stable climate: The curriculum, calendar, and assessment assume children stay put. But in climate-stressed belts, seasonal mobility (for herding, dry-season wage work, displacement after attacks or floods) breaks that assumption.

Advertisement

Without re-entry pathways, a one-term gap becomes permanent exit. Global child-climate risk work and Sahel climate briefs have been clear on the education impact pathways; the operational response in basic education is 5–10 years late.

The Political Economy of Basic Education in the North

Advertisement

Patronage contractors benefit when school building is an end in itself — budgets flow, photo-ops happen, regardless of occupancy or learning.

State politicians avoid tough choices like consolidating schools for security, or re-siting to safer hubs which can be spun as “closing schools,” even if it would save lives and learning time.

Advertisement

Security actors face no binding service-level metrics tied to safe school access; no one loses budget when pupils cannot reach class.

SUBEB leadership often rotates with political cycles; institutional memory for EiE or climate adaptation is weak, so each shock is treated as novel.

Advertisement

Until incentives flip from spending to schooling, the status quo pays and children lose.

A Climate-Proof, Conflict-Aware Roadmap in 12–18 Months

Hard-wire “safe learning hours” as the outcome. Tie federal-to-state UBEC disbursements (including SWAp tranches) to a simple, auditable metric: instructional hours delivered per enrolled child in high-risk LGAs — validated by spot attendance audits and EiE compliance checks. States can spend as they choose; money flows only when safe hours are verified. This moves politics from announcements to delivery.

Make school calendars mobile. In Sahel belts, pilot bi-modal calendars (e.g., compressed terms before migration periods; evening or weekend blocks during peak farm/herding), and formal re-entry windows each term so returning pupils can re-enrol without penalty. Couple with continuous assessment rather than high-stakes, fixed-date exams. This is standard in mobile-population programs globally; Nigeria can localise it.

Protect the commute, not only the classroom. Most dropouts happen between home and school. In high-risk corridors, fund escorted walking groups, community watch points, bike grants for girls with safe-route chaperones, and parent-teacher rapid alert lines connected to local security posts. Evaluate by route-specific attendance gains and incident reduction.

Pay families to keep girls in class when classes actually hold. Expand conditional cash transfers indexed to verified attendance, using safe hours as the metric with higher stipends in conflict LGAs. Evidence from past cash-transfer pilots suggests attendance and retention gains when payments are reliable and conditions are feasible. Don’t condition on exam passes; condition on presence in a safe classroom.)

Fix the “last mile” with radical transparency. Publish LGA-level dashboards each month: schools open/closed, teacher presence, incidents on routes, UBEC/SUBEB project status, safe learning hours delivered. Force peer pressure among commissioners and give parents a map. Tie commissioner performance contracts to these indicators.

The North’s Future is Being Decided in JSS-1

The north’s security, fertility choices, labour market, and civic stability in the 2030s will be overwhelmingly shaped by whether today’s JSS-1 cohort stays in school.

Every kidnapping cycle that goes unanswered by EiE routines, every drought that triggers migration without re-entry, every SUBEB delay that leaves a classroom unbuilt or unstaffed compounds into a legitimacy problem the state cannot police away.

The federal centre has moved some levers providing bigger UBEC envelopes, a results-orientation, and coordination frameworks, but the game is now in state capitals and LGAs. If governors want to bend the curve, they must reward SUBEBs for hours, not headlines; publish the risk maps; and design for mobility in a hotter, more insecure north.

The school bell can ring again on time, in season, and for every child but only if politics, finance, and security are finally made to serve the simple, measurable act of safe teaching time.

Lekan Olayiwola is a public-facing peace & conflict researcher/policy analyst focused on leadership, ethics, governance, and political legitimacy in fragile states.

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.