Five years ago today, a generation of Nigerians, weary of brutal governance and endemic corruption, gathered in peaceful defiance. Their simple request for better treatment and an end to security force brutality was met with live ammunition. The shooting at the Lekki Toll Gate on 20 October 2020 remains a jagged, unhealed wound on the country’s collective psyche.

Today, as we mark this grim anniversary, a recurring pattern of state defiance confirms a tragic truth: the system’s DNA of impunity remains fundamentally unchanged. As I type this, the echoes of 2020 are being heard in the streets of Abuja, where activists led by Omoyele Sowore are challenging the prolonged detention of Nnamdi Kanu and demanding due process for him. One may disagree with their cause (for the record, I do not, even though I find the subject of their cause distasteful), but the resistance, the heavy presence of state security, and the palpable tension are hauntingly familiar. This continuity of state repression against calls for justice is what truly corrodes the foundation of the Nigerian state.

This systemic failure to seek truth and administer justice casts a long, devastating shadow over Nigeria’s economic landscape. For businesses, the violence and subsequent denial were not merely a political tremor; they were an announcement of systemic risk. The unaddressed trauma shattered investor confidence, revealing a jurisdiction where life, property, and the rule of law are precarious. How can Nigeria hope to attract sustainable foreign capital when the immediate aftermath of civil dissent is military engagement, and the primary lesson learned by those in power is that they can act with zero accountability? The economic scars are deep and enduring, manifested in capital flight, a higher risk premium for doing business, and a crippling erosion of institutional trust.

The events of 2020 were not an aberration. Instead, they set a terrifying precedent for the years that followed, creating a grim chronology of contempt for the rule of law.

Advertisement

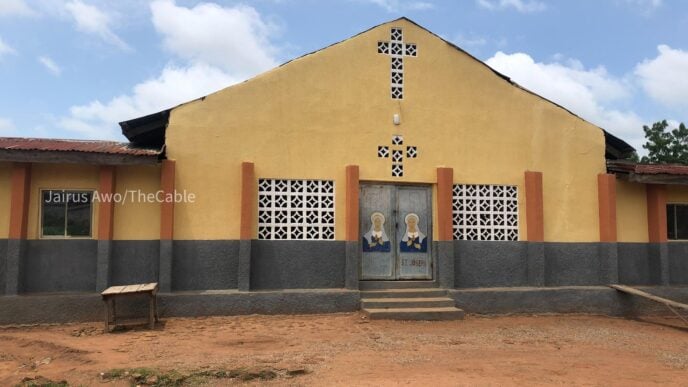

In 2021, a fresh wave of violence engulfed the Southeast in the aftermath of the EndSARS protests. The rise of so-called “unknown gunmen” coincided with alleged extrajudicial actions by state-backed security outfits, notably in Oyigbo, an Igbo-dominated area of Rivers State. A climate of fear took root as hundreds were killed, often with little to no meaningful investigation or prosecution. This solidified the impression that human life was cheap and that certain actors were operating with official immunity. The failure to protect citizens and hold perpetrators accountable in this region marked a dangerous expansion of impunity.

The year 2022 exposed state impunity at its most heinous. Reports surfaced of a widespread, years-long secret military programme of forced abortions carried out against women and girls rescued from insurgency captivity in the Northeast. This alleged systemic violation of fundamental human rights underscored that the impunity was not merely about a few rogue elements, but was woven into the institutional fabric, targeting the most vulnerable victims of conflict.

In 2023, the state’s primary duty to protect life faced its most terrifying test. The horrific massacres in Plateau State during late 2023, where hundreds of innocent lives were lost in organised, protracted attacks across numerous communities, proved that government rhetoric about security reforms was paper-thin. The sheer scale of the violence, coupled with the seeming inability of security forces to prevent or decisively respond to the killings, sent a clear message that certain lives were expendable and the perpetrators were untouchable.

Advertisement

By 2024, the kidnapping for ransom crisis reached a disturbing maturity, becoming a lucrative, quasi-accepted industry across the country. Despite laws outlawing the payment of ransoms, mass abductions continued with brazen regularity, targeting schoolchildren and entire communities. The fact that criminal gangs could operate so freely, turning human beings into commodities for negotiation, demonstrated a catastrophic surrender of state authority and a deep-seated impunity that allowed brigandage to flourish unchecked.

This year, 2025, has brought the absurdity of selective justice into sharp focus with the highly publicised Kwam 1 incident. When the celebrated Fuji musician engaged in unruly conduct, obstructed a commercial aircraft, and doused airline staff with liquid, the state’s response was shockingly lenient. While an ordinary traveller was punished severely for a relatively minor infraction, the celebrity was eventually pardoned and even rewarded with talk of a brand ambassadorship. This double standard screams a simple, corrosive truth: in Nigeria, the rule of law bends for the powerful, cementing the belief that status is the ultimate shield against accountability.

The continued reign of impunity is the single greatest threat to Nigeria’s economic recovery. When elites are seen to operate above the law, it poisons the legal and regulatory environment for everyone. It raises the political risk profile, deters ethical investors, and encourages a culture of corruption and corner-cutting.

Until a genuine culture of accountability is forged, all of the government’s grand investment roadshows and international charm offensives are doomed to underperform. This culture must be one where a politician who steals a billion naira is treated the same as a citizen who violates airport regulations, and where the security services that kill their own people are brought to justice. No amount of marketing can offset the toxic liability of a state that refuses to prosecute its own powerful offenders. The unhealed wound will fester, and until justice is pursued without fear or favour, the economic promise of Nigeria will remain tragically shackled by the past.

Advertisement

Nwanze is a partner at SBM Intelligence

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.