On December 5, 2017, the Swiss government announced that it would return $321 million stolen by Sani Abacha, Nigeria’s late military dictator who ruled from 1993 to 1998. The money was part of the billions of dollars allegedly looted during his rule. The repatriation was big news for many who have been following the development since the return to civilian rule in 1999.

But there seemed to be more about this particular $321 million that would now be handled by Abubakar Malami, Nigeria’s minister of justice and attorney-general under the President Muhammadu Buhari administration.

Just a few days after the announcement by the Swiss government, the Cable Newspaper Journalism Foundation (CNJF) started to track things.

CNJF, a partner of TheCable newspaper, is a not-for-profit organisation using the vehicle of journalism to advance transparency and accountability in government.

Advertisement

For context, the federal government had, between 2013 and 2014, used the services of Swiss lawyers, Enrico Monfrini and Christian Luscher, to recover the stolen funds from Liechtenstein and Luxembourg and domiciled the monies with the attorney-general of Switzerland since then. It is important to note that Nigeria also undertook to pay 4% of the recovered Luxembourg assets as professional fees and expenses to the lawyers, in addition to roughly $6.8 million in fees to be paid to Monfrini for the Liechtenstein recoveries. Enrico had been hired since 1999 by the then-President Olusegun Obasanjo administration to help track these stolen monies.

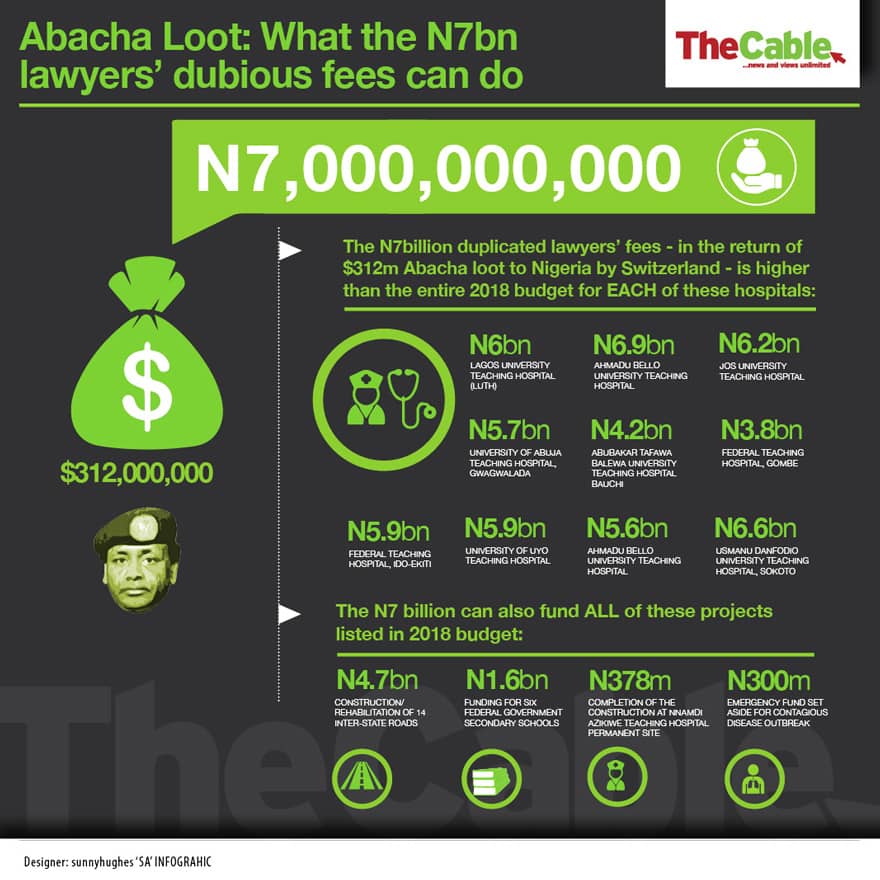

Curiously, Malami again hired two Nigerian lawyers to recover the $321 million Enrico had already recovered. Meanwhile, with the fees settled for the Swiss lawyers, all that was left for the money to be returned to Nigeria was for Malami to sign an MoU with the Swiss authorities and commit to an undertaking that the funds would be properly utilised. That’s simple, right?

Advertisement

On December 22, 2017, TheCable published the first part of the story, which was followed up on for the next five years. This part detailed how Malami simply “created jobs” for the newly hired Nigerian lawyers. The interesting part is that these lawyers, acting on Malami’s behalf, would also take at least another 4% as commission and professional fees from the recovered funds. Nigerian lawyers Oladipo Okpeseyi, a senior advocate, and Temitope Isaac Adebayo were engaged in 2016. It’s also important to note that Okpeseyi and Adebayo were lawyers to the Congress for Progressive Change (CPC), the legacy party of former President Buhari. Also, Malami was the legal adviser to the CPC.

A senior official of the ministry of justice then told TheCable that “this is a case of re-looting Abacha loot”. “A simple letter from the office of our attorney-general of the federation to the Swiss attorney-general requesting the repatriation of the funds to Nigeria consequent upon the signing of an MoU was all that was required to consummate the deal,” the official had said.

Before TheCable went to the press, the newspaper requested — under freedom of information (FoI) — from the office of the attorney-general information on: the agreements between the federal government of Nigeria and the Abachas, which led to the eventual withdrawal of the prosecution of Mohammed Abacha; and why another lawyer was appointed after Monfrini had completed the recovery job.

As the lead reporter on this story, I was disappointed that the office of the attorney general of the federation, being the custodian of the FOI Act, received TheCable’s request on December 8, 2017, and never responded to date. As requested by the law, TheCable sent a follow-up request, still been no response. I also sent a couple of messages to the then minister on his phone, and he never responded. This was after an official in the information department at the ministry advised TheCable to request an interview with the attorney-general, as they do not have the needed details. We just wanted Nigerians to know why new lawyers were being engaged for a job already done.

Advertisement

We reached out to Enrico with what we found. The Swiss lawyer was also shocked by the development. “I don’t know why the federal government of Nigeria decided to appoint other lawyers,” Monfrini said in an interview. He explained that since September 1999, there had been no breach in the agreement he signed with the Nigerian government.

“Upon the election of President Buhari, the newly appointed minister of justice and attorney-general, Malami, appeared to prefer using the services of other lawyers in Nigeria and elsewhere,” he had said.

In April 2018, Kemi Adeosun, then minister of finance, refused to approve the payment of $16.9 million in fees to the two lawyers for the “recovery”. A request had been made to the former finance minister by the justice ministry for the payment to the Nigerian lawyers, but the request was sent back. Adeosun later came under pressure to deny blocking the payment. An ad-hoc committee set up by the house of representatives to probe the dubious fee had described Malami’s engagement of the lawyers as “the height of injustice.”

“Somebody wants to create $16 million in free money for no job done, in this era? Why is the AGF engaging another lawyer? What kind of change are we talking about?’ one of the lawmakers had said. Malami would later resort to delay tactics to frustrate the house of representatives’ investigation. Apart from refusing to provide the documents requested by the ad-hoc committee set up by the house, Malami also decided to use the courts to stall the probe.

Advertisement

MALAMI BLOCKED ALL MEANS OF TRANSPARENCY

After about a year of Malami refusing to answer these questions, I met Adebayo, one of the newly hired lawyers. I was surprised to hear Adebayo argue that Monfrini did not complete the work. He accused Monfrini of advancing his personal interest more than that of Nigeria, his client. We reminded Adebayo that, as far back as 2014, Mohammed Adoke, the then AGF, had written Oliver Jornot, the attorney-general of Geneva, for the money to be paid into the special recovery account of the Nigerian government with the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) — after a 4% deduction had been made as Monfrini’s fees. After which, the money had been available to the Nigerian government as early as December 2014. But why can’t Malami write a simple letter instead of appointing new lawyers? Well, Adebayo said it was not in his place to answer this question.

Advertisement

We continued to stay on the matter. In January 2018, CNJF sued Malami over his failure to respond to a freedom of information (FoI) request on the engagement of lawyers for the recovery of stolen funds. The foundation sought an order of mandamus compelling the AGF to make available the information and documents requested from its office pursuant to the FoI Act, 2011.

“Till the date of bringing this application, the respondent (AGF) has refused to comply with the provisions of the FoIA by his refusal and failure to make available to the applicant (CNJF) the information and documents requested, and/or denial of access to the request for records and information within a time limit allowed by the law,” Kusamotu & Kusamotu, CNJF’s counsel, had stated in the court papers. The counsel added that there is no justification for the refusal and failure to make available to CNJF the information and documents requested as required by section 7 of the act.

Advertisement

For almost two years, the foundation was in and out of the court, just asking for Malami to provide information on this deal. At one point, one of my colleagues emailed Malami on the matter, and he responded that he does not treat such matters with his personal email. This was many months after we had first submitted the FoI to his office. I began to wonder what could be more of an official channel than that.

On September 25, 2019, we got a shocker. The court dismissed CNJF’s suit against the AGF, saying the foundation did not produce certified true copies (CTCs) of its registration documents. The court, with Inyang Ekwo, the presiding judge, said we provided a photocopy of our certificate of incorporation “in contravention of the rules of evidence, which stipulate that such evidence ought to be a certified true copy and not a mere photocopy. Therefore, the court found that the photocopy tendered in evidence was inadmissible”. In clear terms, without looking into the merits of CNJF’s application, the court ruled that the foundation has not been able to prove that it is a duly incorporated organisation that is capable of bringing the action. Throughout this period, not once did the office of the AGF raise any of these issues in its defence.

Advertisement

Our lawyers said the application was decided on affidavit evidence, and that “the law is that any document attached to an affidavit forms part of the affidavit, and does not need to be certified for it to be admissible”. They added that there is no mandatory requirement that the certificate of incorporation should be attached in order to establish a legal right to bring the action, as the FoI Act grants an unqualified right to any person, artificial or natural, to make applications under it. As a journalist, nothing got me this discouraged.

Earlier in June 2019, a coalition of civil society organisations led by the Say No Campaign had also written an FoI request, asking for records of payment for the lawyers. The justice ministry said it won’t provide the information so it does not interfere with pending litigation, hanging this on how we’ve taken the matter to court.

In July 2023, two months after he left office, TheCable reported how the former minister was facing a probe over five suspicious mega deals under his watch, including the duplicated legal fees in the transfer of $321 million of Abacha loot from Switzerland to Nigeria.

Malami later alleged that “Monfrini had demanded a $5 million upfront payment and a 40 per cent success fee, later reduced to 20 per cent, terms the government rejected because they violated official policy”. Why make this revelation eight years later? Of course, this was after the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) had, on November 28, invited him for questioning.

Femi Owolabi, a former head of investigations at TheCable, is the senior special assistant to Governor Biodun Oyebanji on policy research & documentation