Prof Ismail Ibraheem

Three decades on, what else can a two-star—or, if you like, a two-scar—champion of Nigeria’s renowned June 12 presidential election do as a patriot who has chosen to remain in Nigeria, other than to uphold the cause infinitely? Yours sincerely, lost a thriving journalism career to June 12, following the proscription of Concord Press; and therefore, on Abacha hangs my unpaid gratuity to this day.

Short of jumping from frying pan to fire, I subsequently joined the nation’s premier civil rights group, the Civil Liberties Organisation (CLO), which kept me almost permanently on the precipice of jail. But for the courage of the judicial officer who presided over my sedition (?) case and stood for justice, what would my story have been?

As I therefore engage virtually, together with fellow Nigerian scholars, in a discourse focusing on the all-pervading nature of corruption in Nigeria today, commemorating the June 12 anniversary, I suddenly feel a sense of resuming an unfinished business. In any case, every research effort—my current turf—is often open-ended, such that a concluded work may even suggest a future direction.

Back in 2018, the Kano-based, Dr. Y. Z. Yau-led Centre for Information Technology and Development (CITAD), supported by the MacArthur Foundation, needed a scholar-activist as a consulting technical advisor for a two-year anti-corruption consortium project. The lot fell on me. Prior to this, together with Dr. Yau, I served as a consultant to a similar anti-corruption initiative of DFID, called Coalitions for Change (C4C).

Advertisement

After the initial two years on the CITAD–MacArthur project, I was encouraged to conceptualise a project within that same thematic frame of anti-corruption. I came up with the Campaign Against Corruption on Campus (CACOCA), the very first of its kind, focusing exclusively on campus corruption.

As a form of service to my primary professional community, I ran the project with utmost passion, assisted by three colleagues: Mutair Wahab Akinbayo, Dr. Monsurat Ayegusi, and Badirat Hassan. The project, through research, uncovered a dense rot of corruption, tragically encountered on nearly every campus. We established that this rot was only a reflection of the larger Nigerian society.

Nigerian politicians, in and out of government, have thrown caution to the wind and have infected campuses with their conduct. Undaunted, CACOCA bought airtime on LASU Radio for its dedicated programme called Towards Transparency. The programme featured anti-corruption news bulletins and brought together diverse campus opinion leaders to dissect prevailing corruption issues with a solutionist approach.

Advertisement

To ensure the campaign’s longevity, we uploaded our broadcast editions to Spotify. CACOCA broadcasts became so impactful that I received speaking invitations on anti-corruption as far away as Jamaica! It is, however, deeply saddening that corruption remains so terribly intractable. Yet it is fulfilling that the “never give up” spirit is catching on among scholars, evident in the Democracy Day Discourse organised by the Committee on National Issues, Development and Advocacy (C-NIDA) of the Muslim Lecturers Association (MLA).

Like the hawks they truly are, the same set of politicians who had shared beds with soldiers in plundering our commonwealth during the military era (till 1999) have since regrouped with renewed energy. Not only do they now dominate all three tiers of government in Nigeria, but they have also masterfully seized control of most major channels of information. They are the ones with ample resources to publish voluminous accounts shaped by their biases. The worst of such, most recently, was the one conjured by Babangida, the man who annulled June 12.

The surviving foot soldiers of the struggle, obviously weary, have receded to the background, thankful they have lived to witness what appears to be the emerging light at the end of the tunnel. With no facilitator to properly memorialise the struggle, each has retreated to their corner, left to re-strategise individually.

But old soldier no dey die.

Advertisement

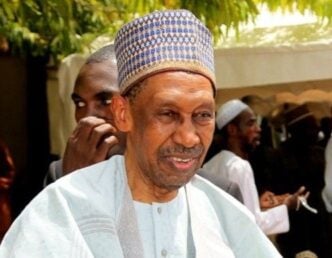

Like me, more young foot soldiers of the struggle era have not only grown but matured, ready again to raise questions about the conduct of the polity, with a view to scientifically charting a way forward. Former editor of CLO’s Liberty Magazine and coordinator of the Journalists Outreach for Human Rights (JOHR), Ismail Ibraheem, has found his voice again—and now, interestingly, as a towering scholar and professor.

In his recent inaugural lecture titled Casino Journalism and the End of History, Professor Ibraheem—now a respected journalism scholar at the University of Lagos—spoke before a distinguished audience at the J. F. Ade-Ajayi Auditorium, including academics from various disciplines. He chose the provocative title to critique the contemporary Nigerian media landscape, now largely overtaken by conscienceless politicians.

He coined the term casino journalism to describe a system where sensationalism, entertainment, and profit drive reporting, prioritising clicks and ratings over accuracy and depth. Its defining traits include randomness and spectacle over robust investigation, and the pervasive influence of the “brown envelope”—accepting gratuities from elites and advertisers. According to Professor Ibraheem, this amounts to a gambling-like attitude: short-term wins replacing long-term credibility.

He argues this model treats journalism as a dice roll, where one never knows which sensational bait might yield the next burst of clicks. Rationalising the “End of History” consequence, he explains that journalistic narratives are losing historical continuity and context. Rather than shaping civic memory, the media now perpetuates media amnesia, moving hastily from one sensational headline to the next.

Advertisement

He cited several Nigerian scandals that lacked historical or contextual depth and recalled how the CLO, ironically, deployed sensational tactics in covering the Abacha 2 Million Man March. These examples underscore how critical media watchdog functions are being undermined by infotainment practices, steered by corrupt governance.

Overall, Professor Ibraheem emphasises the need to curb sensationalism and preserve context, lest Nigerian journalism gamble away its role, and along with it, our collective understanding of history and democracy.

Advertisement

Being based in the United States for over two decades has not distracted Omolade Adunbi either. “Lade,” as we used to call him, was the project officer in charge of the human rights education project at CLO. Unlike Professor Ibraheem, who was British-trained, Lade studied at the prestigious Yale University and is now a professor of anthropology at the University of Michigan.

A relentless researcher, Professor Adunbi has published two major, award-winning books that critically reappraise governance and resource management in Nigeria. The first, published by Indiana University in 2015, is titled Oil Wealth and Insurgency in Nigeria. Drawing from Omolade’s activist background, the book illustrates how NGOs, militant groups, and local social movements deploy ancestral land and resource rights to challenge both state authority and multinational oil corporations. These actors marshal powerful symbols to justify disruptive actions, from protests to armed rebellion. Adunbi emphasises how oil wealth reshapes people–environment relations, as communities pivot toward oil rents, triggering new governance forms, solidarities, and exclusions.

Advertisement

In Enclaves of Exception, Adunbi builds on his earlier work by investigating newly expanding domains of extraction—free trade zones and artisanal oil refineries. Comparing SEZs and artisanal refineries, he identifies both overlaps and divergences. Though SEZs are hailed as engines of growth and modernisation, Adunbi shows they mirror the environmental degradation caused by illegal refineries. Both systems result in pollution, damaged water systems, public health threats, and the displacement of traditional livelihoods.

The book interrogates the relationship between global capital and local resource claims. It reveals how communities—whether operating within formal SEZs or informal outfits—participate in and are shaped by extractive regimes. These “enclaves of exception” are zones where legal, environmental, and social norms are deliberately suspended in pursuit of economic gain.

Advertisement

Most significantly, these works highlight the paradox of oil: a source of wealth that also dispossesses; that brings jobs, but also conflict, reconfirming the long-held thesis of the resource curse.

The CLO was a fertile nursery for many of the leading lights of the June 12 struggle, then mere project officers. It is deeply gratifying to see that a few intellectual oaks have since sprouted and continue, voluntarily, to sustain the campaign for progressivism—whether or not the so-called “Renewed Hope” government believes in the need for proper memorialisation of June 12.

Tunde Akanni, professor of journalism and development communication at LASU, Nigeria, was head of campaigns at the CLO between 1994 and 1998. You can reach him on X: @AkintundeAkanni

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.