The judgement of the federal high court in Lagos last week ordering the government to fix prices of some goods and services in seven days has triggered speculations that the government might be considering a reintroduction of price control. Justice Ambrose Lewis-Allagoa specifically asked the federal government to determine the prices of milk, flour, salt, sugar, bicycles and their spare parts, motor vehicles and their spare parts and petroleum products such as petrol, diesel and kerosene.

The order was contained in the judgement in a suit filed by Femi Falana against the Price Control Board and the Attorney General of the Federation according to Section 4 of the Price Control Act of 2004. Falana had sued the Board and the AGF to fix prices of the items but the respondents did not file any defence. The court order has set off speculations that the government might undo its deregulation policy. However it should be noted that the court order was for the government to fix the prices of the mentioned items; it did not specify whether the fixed prices should be above or below market rates.

Price control, first used by the military regime of Gen. Obasanjo in the 1970s, is a government order that stipulates a maximum or minimum price to be charged for specified goods and services, especially during periods of war or high inflation, as we have today. The minimum price is called price floors while the maximums are price ceilings. But with the continued expansion and liberalization of the economy over the years, price control has become largely otiose, although the government is still fixing price floor for wages and salaries (minimum wage). In 2004, the Obasanjo administration reenacted the Price Control Act and set up Price Control Board.

The law remained largely unknown and unheard of until Justice Lewis-Allogoa’s pronouncement last Wednesday. If the federal government had been diligent enough to enter a defence and argue against price fixing, the judge might have given a different order. I await the government’s next move, but for now, I caution that reintroducing price control would be counterproductive and difficult to enforce and, in addition, create unintended consequences.

Advertisement

Price control could lead to shortages of goods and services as producers become less incentivized to produce them at lower prices, and this may result in the emergence of black markets where the goods are sold at higher prices than the regulated prices. A good example is the foreign exchange market where black market has become a major determinant of reference prices.

Another challenge is that price regulation could also result in reduced investments and innovation in some sectors as producers may be less motivated to make huge investments if they cannot raise prices to recoup their investments. This is one of the reasons that foreign investors shied away from investing in refineries in Nigeria.

Regulated prices of refined products were considered major disincentives. Proliferation of fake products as genuine producers cannot produce at regulated prices is another problem of price control, and as I said earlier, price control could be very difficult and costly to enforce. Government will have to deploy regulators or ‘’mystery shoppers’’ to go from shop to shop to catch violators. Trust Nigerians, another set of extortionists and bribe takers would emerge. Every unemployed youth and motor park ‘agberos’ would want to enlist in the Price Brigade! I urge the government to abandon any idea of a return to price regulation.

Advertisement

The leading cause of inflation in the country is food inflation, and to address this problem, it is important to note that Nigeria is not suffering from shortages of food and basic commodities. In fact, our markets are still full of food items in large quantities.

Rather, the problem is that people do not have money to buy the food they want in the required amount and quality. This is known as food insecurity. Our problem is not food shortage, but food insecurity. I should note that this is not developing countries’ problem alone. There are many cases of food-insecure households even in the US and some European countries, and they have devised many programs to check it. We should. First, there’s a strong need for employers to increase salaries of low-income earners in their organizations. It’s heartening that the federal government has started minimum wage discussions with the NLC. Second, state governments should establish some kind of food stamp programs in which governments buy basic items in large quantities and resell at reduced prices to the vulnerable members of the public.

It was common in the 1970s and ‘80s in the old Cross River State and I am not surprised that Akwa Ibom State government is already planning to bring back the scheme. But the government should guard against possible abuse by light-fingered officials. Third, every household should be encouraged to grow own food crops, especially annuals (those crops that are grown and harvested under one year), and raise poultry. Every civil servant should be mandated to own a farm and Fridays should be declared work-free to enable them go their farms. This is an emergency.

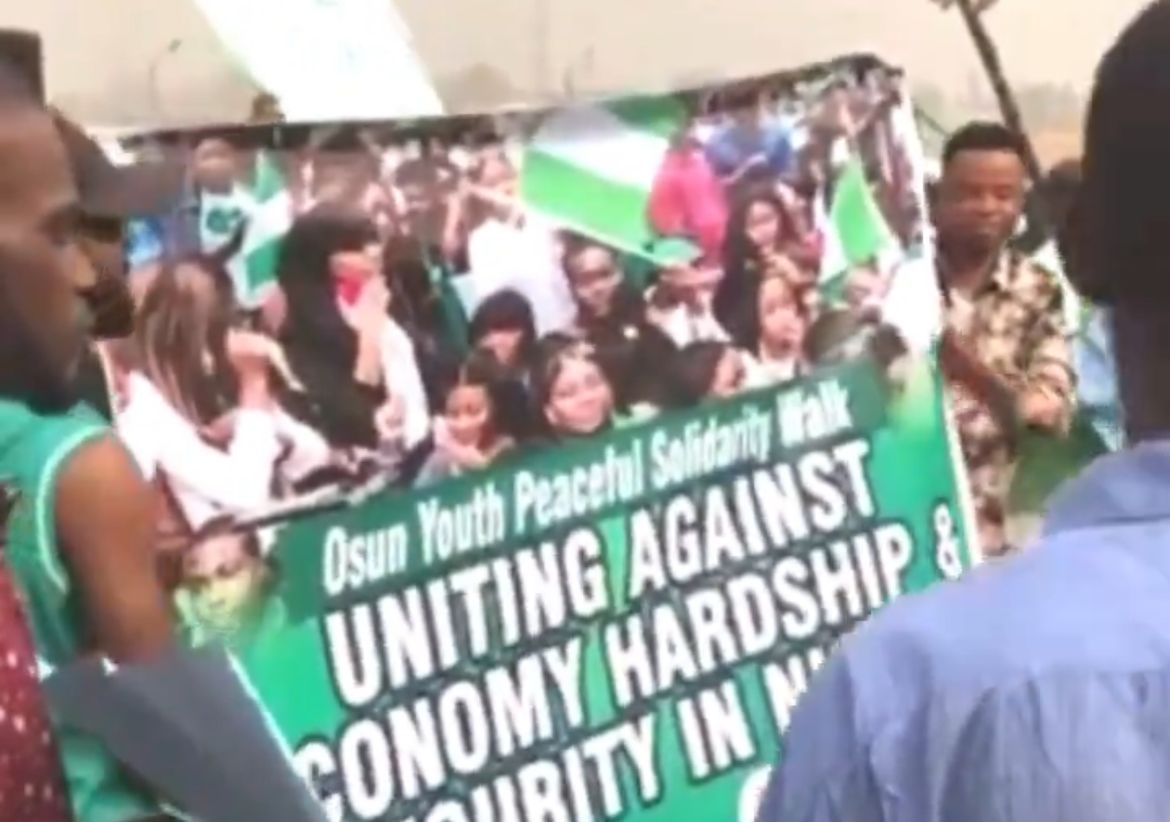

Food insecurity and large-scale hunger in a large population such as ours pose serious national security challenges. The outbreak of protests in some northern states last week where, incidentally, poverty is very pervasive should be early warning signs that things may go out of hand.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment