In the early hours of April 15, 2025, armed men wielding firearms and cutlasses attacked Natasha Akpoti-Uduaghan’s residence in her Kogi hometown. They shattered windows, vandalised property, and tore through the compound searching for the senator representing Kogi central. But the suspects had received false intelligence about her location.

The attack marked the peak of a campaign that had begun online: a rising tide of digital slander, coordinated smears, and personal attacks triggered by Akpoti-Uduaghan’s political fallout with Senate President Godswill Akpabio, Nigeria’s third most powerful public official.

The tension between Akpoti-Uduaghan and Akpabio had been brewing long before the attack. On March 24, 2024, both lawmakers attended the 148th Inter-Parliamentary Union in Geneva, alongside other Nigerian senators. A selfie Akpoti-Uduaghan posted on Instagram would later be plucked from context and weaponised online.

Social media users fixated on her proximity to Akpabio, spinning it into supposed “evidence” of a romantic entanglement with the senate president — a rumoured affair that quickly curdled into an ugly mess.

Advertisement

Some four months later, the duo had a public clash. During a senate sitting, Akpabio shut Akpoti-Uduaghan’s speech down, asking her not to speak like she was in a “night club”. His comments drew ire from the public, especially as weeks prior, Ireti Kingibe, a senator representing the federal capital territory (FCT), was silenced when she protested that she was being excluded from the affairs of the nation’s capital.

Akpabio apologised only after blogs made numerous posts linking him to several women in a string of alleged extramarital affairs. Things quieted down for about a year until February 20, sparking a targeted abuse that spilled beyond social media timelines into her real life.

POLITICS, POWER, AND RETALIATION

Advertisement

Senate seating arrangements have been a topic of dispute in the past. Lawmakers positioned in front-row seats near principal officers, elevated sections, or aisle spots are more likely to catch the presiding officer’s eye during plenary sessions, increasing their chances of being called to speak.

After a wave of defections to the ruling party, some seats were reassigned, and Akpoti-Uduaghan was among those affected. But during the February 20 plenary, she ignored her new placement and returned to her original seat, citing a refusal to be “bullied”.

At the height of the disagreement, Akpabio called for security officers to remove her from the chamber. The senate later condemned Akpoti-Uduaghan’s seat reassignment protest, accusing her of using the red chamber for “content creation”.

In a media interview the following day, Akpoti-Uduaghan claimed she had been subjected to intimidation, exclusion, and a denial of official travel privileges since joining the senate. Then, on February 28, the senator publicly accused Akpabio of sexual harassment in an explosive interview. The reactions were swift, sharp, and biting.

Advertisement

The first consequence was Akpoti-Uduaghan’s referral to the senate committee on ethics, privileges, and public petitions for disciplinary review for sparring with the senate president. The Kogi senator later tendered a sexual harassment petition against Akpabio to the upper legislative chamber, but the senate panel rejected the petition, citing due process breaches and legal limitations.

On March 6, Akpoti-Uduaghan was suspended for six months as a lawmaker, with her office locked and her allowances and security details withdrawn for the time being.

Refusing to stay silent, Akpoti-Uduaghan has since granted multiple media interviews locally and internationally and has taken her case to the IPU, a global organisation of national parliaments.

THE WAVE OF ONLINE ATTACKS

Advertisement

Born to a Ukrainian mother and a Nigerian father, Akpoti-Uduaghan’s appearance has often been used to draw parallels with her perceived competence — a subtle yet persistent form of bias.

In a defamation suit, Akpoti-Uduaghan frowned at Akpabio’s comments over her visage when he said, “she thinks being a lawmaker is all about pancaking her face and wearing transparent outfits to the chambers”. Pancake is a local parlance for makeup. Akpoti-Uduaghan said the senate president’s comments were defamatory, provocative, disparaging, and lowered her dignity in the eyes of her colleagues and the right-thinking public.

Advertisement

The senate president’s words reverberated beyond that moment; soon, other lawmakers began parroting the same language, embedding ridicule into their description of Akpoti-Uduaghan.

“And I don’t know what is wrong with this lady. Does she think that she’s the most beautiful woman on earth? Or is it because she’s that chocolate colour. In my own assessment, she’s not among the beautiful women in Nigeria, and it is high time we come hard on her,” Senator Peter Nwaebonyi, deputy chief whip, said in an interview.

Advertisement

On X, the video was viewed more than 440,000 times, reposted 1,000 times, with another 1,000+ comments, and over 300 bookmarks.

Soon, the rhetoric leapt from the senate floor to the minds of social media users, where it took on a life of its own.

Advertisement

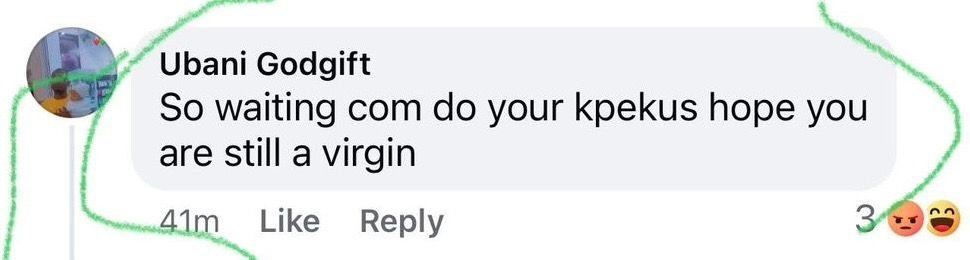

Chigozirim Emeakayi, a Facebook user, took on the task of spreading this content.

Between the time of Akpoti-Uduaghan’s clash with Akpabio till May 2, Emeakayi made over 20 posts hurling abusive words at the Kogi senator.

“Natasha Akpoti is a good example of beauty without brain. If this nuisance of a woman is not recalled and replaced before six months, we have failed as a nation,” one of his Facebook posts reads.

It gathered over 144 comments with some 100 “mocking” reactions.

“Meet Natasha Akpoti, the most beautiful liar on earth!” another post with over 200 comments and reactions said.

The smears spread into her marital life with Emmanuel Uduaghan.

Uduaghan had accompanied his wife to the upper legislative chamber when she went to submit the sexual harassment petition against Akpabio. Before she made her way to the plenary, the couple shared a brief kiss.

Yemi Adaramodu, senate spokesperson, said his stomach churned when he watched clips of the kiss. He said the couple’s display of affection, in the full glare of television cameras and a battery of reporters, was “unthinkable and unspeakable” and morally wrong.

Nwaebonyi was very vocal in his criticism of not only Akpoti-Uduaghan’s appearance but of her marital life.

The senate deputy chief whip accused Uduaghan, a monarch, of marrying her out of pity, labelled Akpoti-Uduaghan a “gold digger, habitual liar, and habitual blackmailer”, and claimed she had six children from different men.

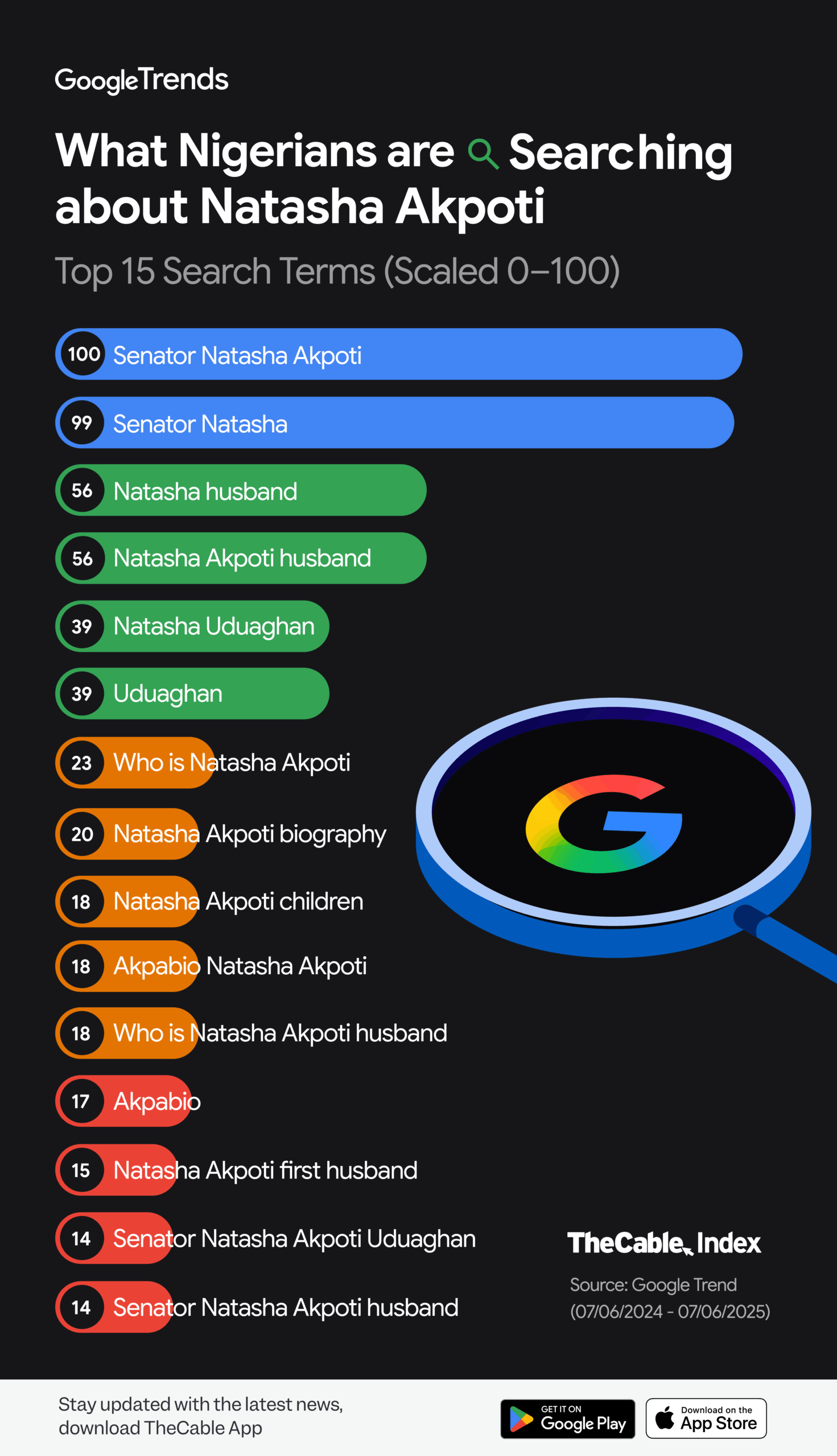

Opinions about Akpoti-Uduaghan’s private status have often taken centre stage. A Google Trends analysis showed that searches around the topic during the height of the controversy superseded insights into her career.

Akpoti-Uduaghan said Nwaebonyi’s comments were false, malicious, and defamatory, and had caused her emotional distress and reputational damage during a turbulent time. She sued the senator for N5 billion, but the damage had been done. Sentiments spread like wildfire on social media, and sensationalist reports began to seep into mainstream media.

One X user urged Akpabio to spin the table on Akpoti-Uduaghan and accuse her of sexual advances without evidence.

The tweet was viewed 181.8k times, had 1.1k likes, 560 comments, and 259 reposts.

EZEKWESILI CAUGHT IN THE CROSSFIRE

Very few people publicly sided with Akpoti-Uduaghan in her standoff with Akpabio. One of the few who did was Oby Ezekwesili — a former vice president of the World Bank and two-time minister under former President Olusegun Obasanjo.

But Ezekwesili was no stranger to the vitriol. During her time in government, she endured her share of gendered attacks — from whispers about her closeness to Obasanjo, to outright attempts to question her legitimacy and authority in male-dominated spaces.

In March, Akpoti-Uduaghan submitted a fresh petition to the senate committee on ethics, privileges, and public petitions.

Ezekwesili joined Abiola Akiode, counsel to Akpoti-Uduaghan, and the petitioner, Zubairu Yakubu, at the senate committee hearing.

Yakubu had made efforts to speak while Neda Imaseun, the senate committee chairman, was speaking, but he was asked to turn off his mic.

When Ezekwesili tried to intervene, Nwaebonyi — who appeared as Akpabio’s witness — interrupted her. She then told him to “shut up”, “compose himself and stop making noise”, which immediately sparked an outburst from the senator.

“You’re a fool. What do you mean? Why are you talking to me like that? I will not take it. You’re an insult to womanhood. People like you cannot be here,” Nwaebonyi replied Ezekwesili.

The shouting match degenerated into vulgar name-calling and gender-based humiliation. Nwaebony said he did not regret insulting the former minister.

Ezekwesili said her dispute with the senator brought to light the challenges women face in society, particularly in spaces of power and accountability. She insisted that Akpoti-Uduaghan deserved justice and said she would not stop seeking accountability.

But amid her public show of support for Akpoti-Uduaghan, Ezekwesili got caught in the crossfire of gendered attacks, again.

“Former national side chick,” an X user replied to a post lauding Ezekwesili’s achievements. The post made 2.8k impressions and was accompanied by a picture of the former World Bank official with Obasanjo.

As with Akpoti-Uduaghan, the criticism Ezekwesili faced followed a familiar script, eventually zeroing in on her appearance.

“Being ugly on the outside is not the Problem. The main problem is being ugly both on the outside and inside. Oby Ezekwesili is a perfect definition the above definition. A woman who eats and drinks from the plate of hate and vile,” an X user tweeted.

The tweet was viewed 59.3k times, had 584 likes, and was reposted 161 times. Most of the 246 comments were in mockery.

The barrage of insults to Ezekwesili’s appearance was triggered by a comment from Reno Omokri, a social media influencer, who openly criticised the former minister’s exchange with Nwaebonyi.

“Oby Ezekwesili’s manners are in equal proportion to her beauty!” Omokri tweeted.

Most of the 1.2k comments of the tweet, which was viewed 334k times, were scornful and offensive.

NO WOMAN LEFT BEHIND

In Nigeria’s hyper-online culture, fame is rarely a shield, especially for women. Whether in politics, literature, or music, even the most celebrated figures are not immune to the gendered crossfire.

While Akpoti-Uduaghan and Ezekwesili found themselves dodging digital spears, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the internationally acclaimed author and feminist, and Ayra Starr, the music sensation, were embroiled in accusations disguised as moral outrage and disinformation attacks.

In an interview on May 1, Adichie admitted that she regretted publicising having her twins through surrogacy.

Attacks on the author’s personality were not unfamiliar. During the 2023 elections, she faced heavy criticism for her political views. Later, a string of anonymous accounts claimed that her deceased father was arrested.

On February 15, the author revealed that she had twin boys through a surrogate.

From the moment the revelation was made public to the May 1 interview, where she addressed the feedback, thinkpieces, mostly critical of her decision, flooded the internet.

“Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie using a surrogate to get twin boys is ridiculously disappointing,” an X user said.

The tweet gathered 2.6m views, 4.7k likes, 1.8k reposts, and over 800 bookmarks.

Some of the backlash drew sharp parallels between her decision and her feminist ideals.

In her May 1 interview, Adichie said she hated that anything about her decision would become politicised. Her concerns fell on deaf ears.

“But you should be ashamed to use a surrogate, especially to call yourself a feminist and use your class position to exploit a poor woman in the same way men have always done,” an X user replied to the video where the author spoke.

The reply had 8k views and over 100 likes.

The same sentiment echoed across Facebook users.

Ayra Starr found herself in a similar position. However, unlike the others whose backlash stemmed from a specific decision or action, the attacks against the 22-year-old seemed to emerge without clear provocation.

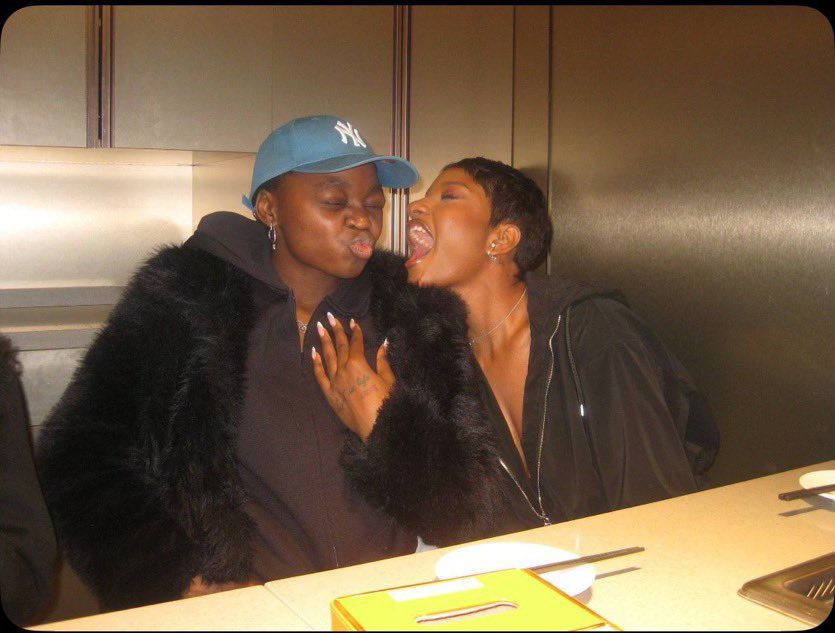

In early May, as online attacks against the other women reached a fever pitch, a narrative about Ayra Starr having bad breath suddenly began circulating on social media.

Multiple screenshots pulled from videos of the artiste interacting with other celebrities, including Rihanna, Tems, and Rema, her co-label star, were posted across multiple accounts to “prove” the narrative true.

But the screenshots were taken out of context.

For example, in a 27-second video clip, Tems and Ayra Starr are seen miming to Commas, Ayra’s hit song. At the 14-second mark — the moment that later went viral — Tems briefly holds her nose while Ayra makes a playful gesture, as if waving off a smell. The lyrics at that point say, “I’m allergic to…”.

It was one of several screenshots, captured at suggestive angles, that amplified the smear campaign against her.

Much of the conversation also migrated to TikTok, driven largely by the platform’s younger user base, which actively engages with pop culture and entertainment narratives.

THE OSINT TRAIL

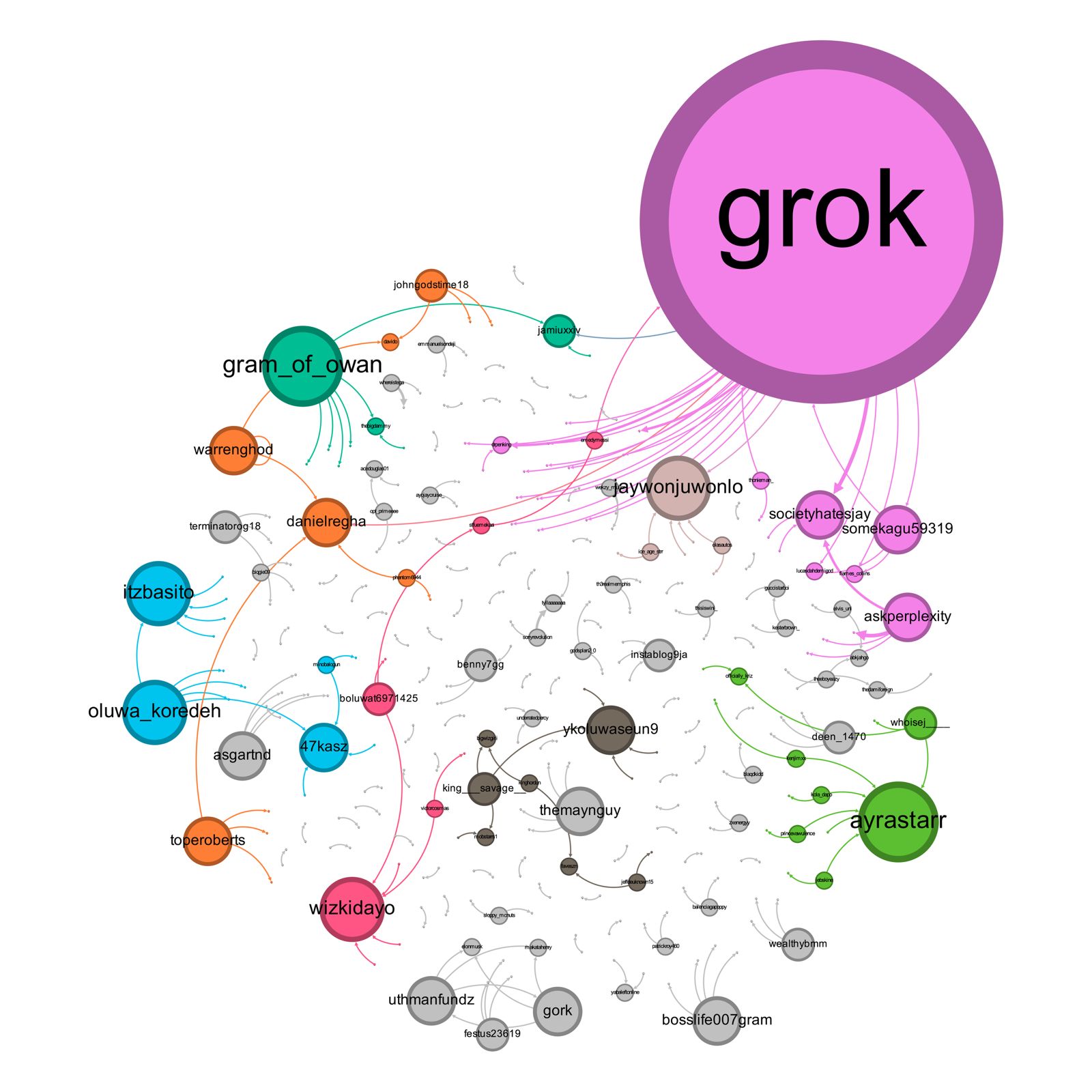

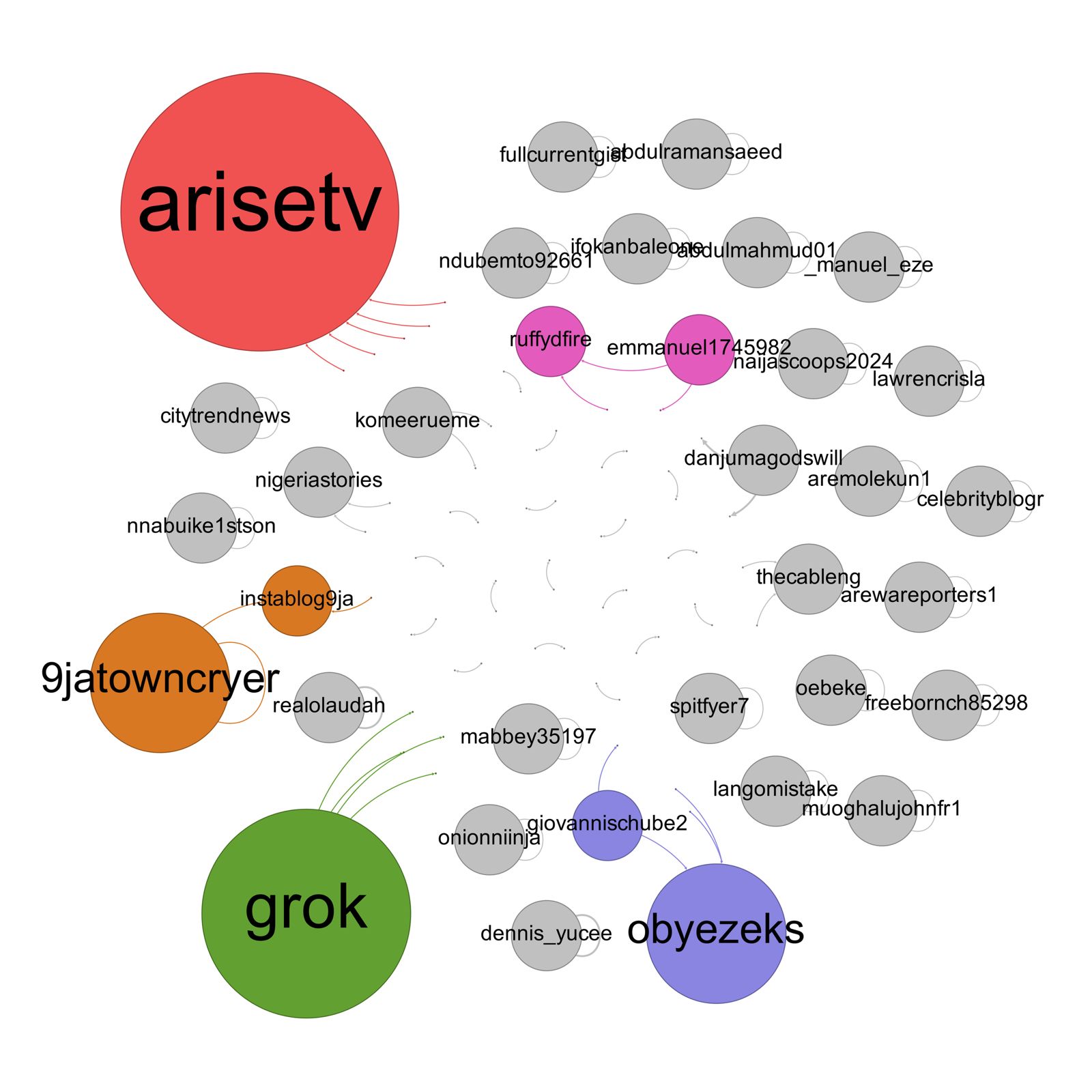

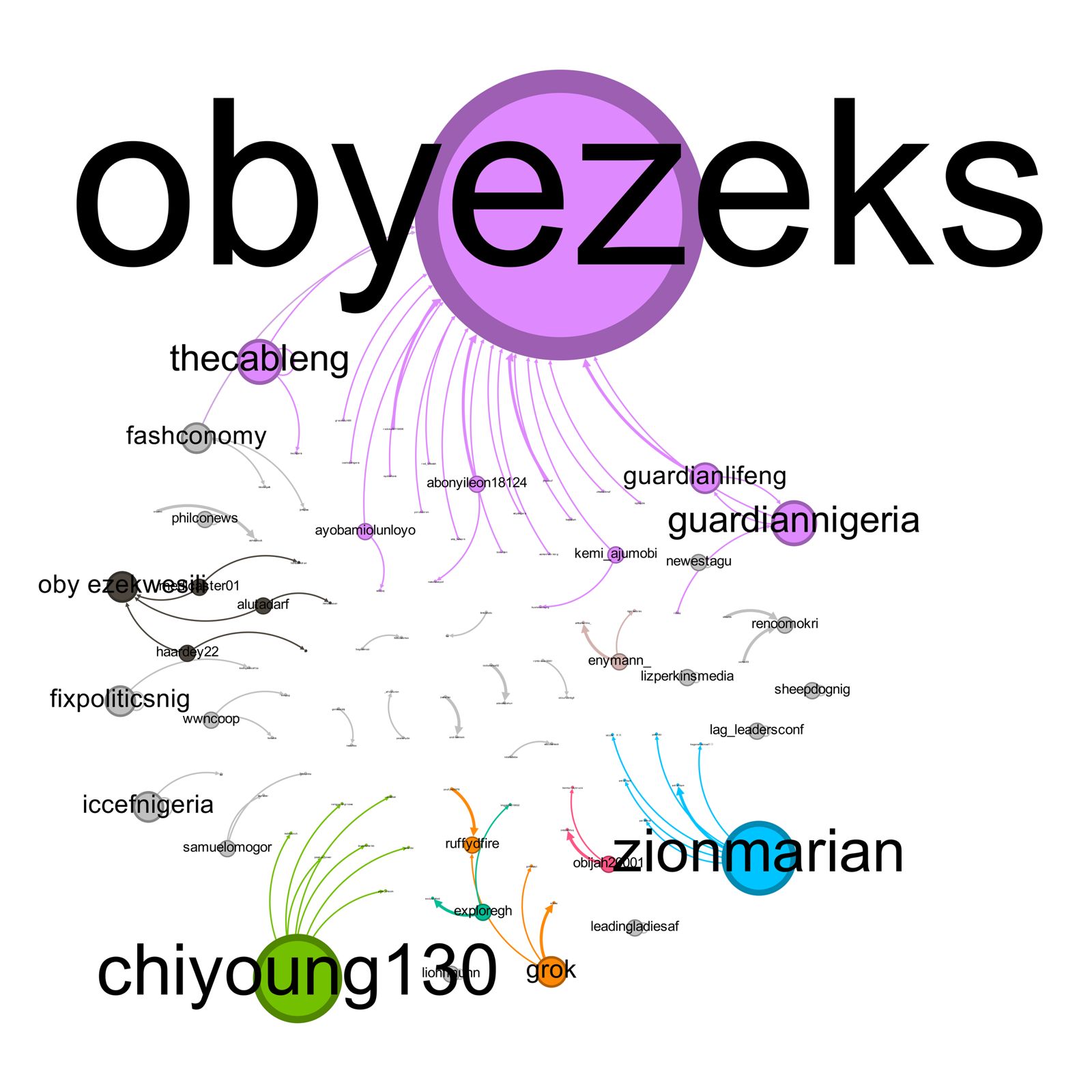

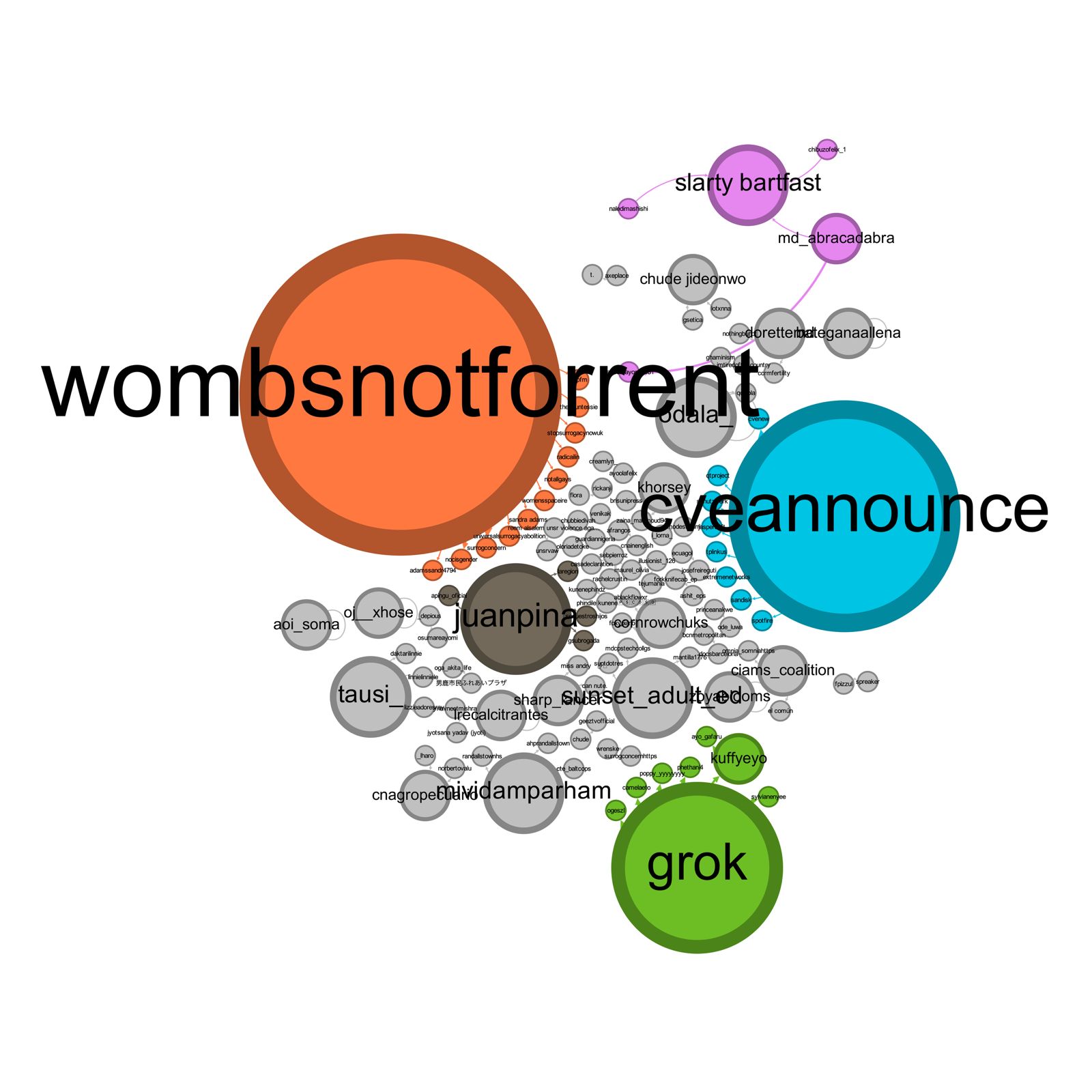

Using X’s advanced search function, multiple tweets were scraped from the platform using Boolean search queries containing keywords and hashtags to assess whether the hostility stemmed from random users or was part of a coordinated campaign.

After preprocessing, the cleaned tweets were loaded in Gephi, an open-source network analysis and visualisation software, where the Louvain modularity algorithm and ForceAtlas2 layout algorithm were used to cluster users and generate interaction network graphs. The Louvain modularity algorithm is a method for identifying groups, or “communities,” within large networks. It looks for areas where nodes (or users) are more connected to each other than to the rest of the network, and checks how strong these groupings are compared to what might happen by chance. The ForceAtlas2 algorithm, on the other hand, is handy for network visualisation.

CableCheck could establish that several networks of accounts spun conversations around these women. It is important to note that an account’s presence in the network graph does not automatically mean it was spreading disinformation or involved in a coordinated activity. The graph only shows participation in the broader conversation, not the specific content or intent, which would be difficult to determine. For instance, the appearance of credible media outlets simply reflects that the topic was prominently featured in their coverage.

Conversely, CableCheck found accounts in the clusters that actively posted about these attacks. For example, in Ayra Starr’s interaction graph, tweets from users linked to @societyhatesjay (in the purple cluster) and @WarrenGhod (in orange) were mostly negative conversations about the topic.

On May 2, @societyhatesjay tweeted in Pidgin English, asking his 46.9k followers if Ayra Starr smells. The post was accompanied by two screenshots from suggestive angles. The tweet gathered 2.4m views, 22k likes, 1.9k reposts, 1.7k bookmarks, and over 800 comments.

Jay’s campaign against Ayra started as early as February. In a tweet, he mocked Ayra and @lotoscuffs_, a video vixen, who also recently suffered attacks to her appearance, for “smelling”.

CableCheck also observed that many social media users actively engaged Grok, the generative AI chatbot developed by xAI, either to seek clarification or to make mischievous and provocative requests.

For example, under a post showing a woman who “disgraced her life time generation”, an X user asked Grok who Akpoti-Uduaghan was.

CRAFTED TACTICS SETTING BACK PROGRESS

The smear campaigns targeting Akpoti-Uduaghan, Ezekwesili, Adichie, and Ayra Starr do not exist in isolation; they are part of a broader pattern of gendered disinformation engineered to discredit, distract, and ultimately silence women in high positions, especially those who do not conform to gender-based expectations.

Nigeria’s persistently low female representation in politics has long been a point of concern — a striking contradiction in a country where women make up half of the population.

In the lead-up to the 2023 elections, there was cautious optimism among stakeholders that the tide would turn and that more women would secure seats in the national assembly.

But the outcome was grimmer than in previous cycles.

Out of the 423 national assembly seats declared by the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), only 15 were occupied by women. This means women represent just 3.5 percent of the elected legislators, while men take up the remaining 96.5 percent.

Out of the 35 state assemblies in the country, only 21 have at least one woman as a member, while 14 of the states have no women at all as lawmakers.

The poor outlook has drawn concern from multiple stakeholders.

According to the IPU, Nigeria ranks 179 out of 183 in terms of women’s representation in national parliaments globally, despite being Africa’s most populous democracy.

Akpabio said Akpoti-Uduaghan’s escalation of the sexual harassment claim was “unnecessary” and warned that her actions may block women from getting political appointments.

A state of online harms survey from Gatefield shows that 58 percent of Nigerian women experience the highest rates of online harms. Gatefield, alongside partners that include big tech platforms and regional institutions, advocates and creates campaigns that bring about positive social change.

In the survey, X was noted as the platform where most Nigerians experience online harms (34 percent), followed by Facebook (29 percent) and WhatsApp (12 percent). The report has yet to be made public, but its preliminary findings were shared with CableCheck.

Hannatu Asheolge, spokesperson for the national online safety coalition, told CableCheck that gendered attacks are “very strategic”.

“We’ve seen it again and again where powerful women are targeted with disinformation to tear them down,” Asheolge said.

“We saw what happened with Senator Natasha…people talking about how many sons she has from how many fathers as if that is important, trying to cast doubt on her character and credibility,” she said, also adding Aisha Yesufu, an activist, and Kadaria Ahmed, veteran journalist to the list of other women who have suffered targeted attacks to their character.

She noted that it is used as a tool to shrink women and scare others from also being as bold or as unapologetic.

“This means that women are actively pushed out of politics, economics, governance, or business. And we all lose because women’s full participation is essential to progress,” Asheolge added.

“When disinformation sidelines women, it doesn’t just affect them; it holds back the entire country. It blocks talent and reinforces the very systems that we’re trying to dismantle.”

WHEN PROTECTION FALLS THROUGH THE CRACKS

Despite the clear escalation of gendered disinformation targeting women in public life — from senators to cultural icons — institutional responses have been alarmingly absent or muted.

In Akpoti-Uduaghan’s case, the Nigerian senate failed to follow global best practices for handling sexual harassment allegations, especially those involving individuals in positions of power.

In many other democracies, officials facing such serious accusations temporarily step aside, allowing for an independent and transparent investigation to take place.

In 2022, Chris Pincher, a UK Conservative MP and former deputy chief whip, resigned from his position after allegations of sexual assault surfaced. Following a parliamentary standards commission report recommending an 8-week suspension, Pincher lost his appeal and resigned his seat in parliament in September 2023.

David Van, an Australian senator, faced multiple sexual harassment allegations and resigned from the Liberal Party in June 2023 amid the scandal.

In many cases, the accused steps down while the accuser is given a fair hearing. In Nigeria, the reverse played out, revealing a troubling institutional tolerance for retaliation against women who speak out.

Beyond the legislative arm, the wider machinery of the Nigerian state — including regulatory bodies and the justice system — has often been accused of weaponising laws intended to curb online abuse to instead suppress free speech.

Meanwhile, social media platforms, where much of the vitriol thrives, face little pressure to strengthen content moderation in ways that reflect Nigeria’s diverse linguistic and cultural landscape.

Even within civil society, where advocacy and protection are typically expected, responses have been uneven. While some organisations issue statements of solidarity, others mobilise protests or calls that oppose the women involved, muddying the waters around what is constitutionally required and morally consistent.

MDAs like the information ministry and the National Orientation Agency (NOA) have often made broad statements against the dangers of false information, but have shown little urgency in addressing its gendered dimensions.

Ironically, the agency recently responded swiftly to an auto dealer who mocked civil servants’ purchasing power, saying the remarks cast public workers in a bad light— yet it has lagged in its response to the targeted disinformation and abuse faced by women in public life.

In mid May, the federal government instituted a defamation suit against Akpoti-Uduaghan, with Akpabio as one of the complainants.

On June 19, she stood before the court—not as the defamed, but as the alleged defamer.