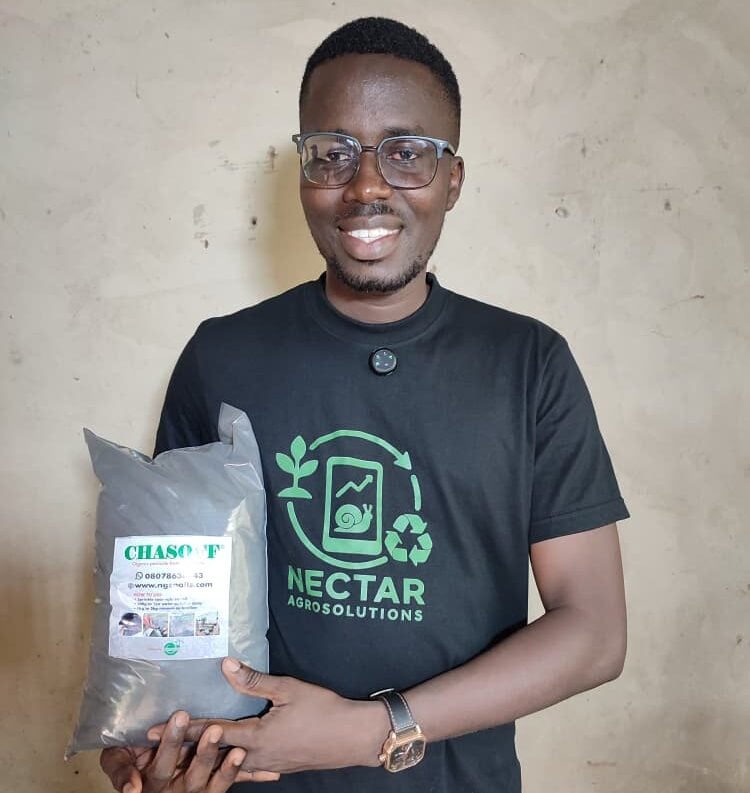

Olajumoke holds a snail shell about to be processed

Ezekiel Olajumoke did not plan to become a snail farmer, let alone an agri-innovator. But a deeply personal event would change his path and, perhaps, the trajectory of Nigeria’s agribusiness scene.

The most remarkable breakthrough for the 35-year-old founder of NGsnails came out of a near disaster, when a swarm of fire ants invaded his farm, attacking from beneath the soil and leaving his pens littered with empty snail shells.

Faced with the possibility of losing everything, he began researching how to protect his snails without harming them, and the answer was unexpectedly hidden in the very shells the ants had left behind.

With months of experiments and a few failed trials, he developed CHASOFF — an eco-friendly, shell-based biopesticide that repels ants without toxic residue.

Advertisement

“What made the situation critical was that these ants were coming from underground. You can’t just spray them on sight. They had to be removed completely,” Olajumoke told TheCable.

“I started researching and came up with a product made by recycling snail shell waste into a bio-pesticide. This product can even be used while the snails are still on the farm.”

According to Olajumoke, CHASOFF is a bio-pesticide that drives ants away from snail farms without harming the animals. It is applied before the ants attack and works more as a preventive measure than a curative one.

Advertisement

To produce CHASOFF, the agriprenure feeds the snail shells into a machine and further refines it to either produce bio-pesticides, bio-fertilizers, or briquettes (biological charcoal).

This trio of products ensure that the snails are protected from ants, the farms yield enough crops to feed them, and the briquettes provide a clean source of heat for drying the meat before export.

According to him, the briquettes do not leave any smoky taste on the processed snail meat, making his products unique and healthier for consumption.

HEALING THAT SPARKED THE CALLING

Advertisement

Olajumoke’s journey into snail farming began far from the farm. While studying molecular biology and genetics at the University of Lagos, his grandmother suffered a partial stroke.

At the hospital, a dietician gave the family a choice — conventional medication or food therapy that included snail meat and snail fluid.

They turned to food therapy, but sourcing snails during the dry season was a rude awakening as prices soared, supply dwindled, and sellers grew increasingly impatient.

“Instead of drugs, the doctor placed my grandmother on snail meat and snail fluid. In nine months, she was walking again without her crutches,” he said.

Advertisement

“During the time my grandmother was sick, the biggest challenge was the high cost of snails in the dry season. I realised snails had this healing power that nobody was really exploring. That was what motivated me to look deeper into snails.”

In 2013, he began collecting snails after rainfall and experimenting with breeding. Losses came quickly and often, and he discovered that not all species reach market size and that environment and soil also matter.

Advertisement

By 2017, he made his first sale of N13,000 to a restaurant, and that was how the idea of scaling his snail business kicked off.

“It was strange for people to see a young guy breeding snails, especially in a Yoruba background where dreaming about snails is seen as a bad omen. But with my research background, I knew there was something bigger here,” he added.

Advertisement

Most snail farmers confine their livestock to cages or concrete pens, but Olajumoke took a different approach — developing a system that allows the snails to graze freely in open farm spaces with trees, herbs, and medicinal plants.

It was within this expanded system that the ant problem struck hardest. The red fire ants were nearly impossible to track and could wipe out hundreds of snails overnight.

Advertisement

Rather than being deterred, he turned the challenge into an opportunity, repurposing snail shells into an eco-friendly farm solution.

“On our farm, we grow trees, herbs, and medicinal plants. For example, we have bitter leaf, and when snails feed on it, they retain some of its properties in their meat,” he added.

“So, when you eat our snails, you’re not just eating protein; you’re also consuming natural nutrients from the plants they’ve fed on. In a way, your food becomes medicine.”

FROM LOCAL PENS TO GLOBAL MARKETS

Before introducing CHASOFF to the market, Olajumoke tested the product for a full year on his farms, and the results proved consistent, giving him the confidence to supply it directly to farmers.

Today, CHASOFF is trademarked and already in use by more than 1,500 outgrower farmers.

“The product has been in existence since 2023. We gave it to our outgrower farmers to test just last year, and the result has been awesome. That was why we decided to launch this year,” he said.

Olajumoke‘s ambitions stretch beyond his own snail pens, as he envisions franchising NGsnails across the country, integrating snail farms into crop-farming communities, and deploying on-site machines that recycle shells into CHASOFF.

He said a central collection system would help in managing both national supply and export distribution.

According to him, a European company now uses refined snail shells from his company as edible-grade calcium for toothpaste — one that proves his ideas have international relevance.

Still, he admitted the journey has been far from smooth. At one point, his snails began dying from the fruits he was feeding them. This setback pushed him to start cultivating his own crops to ensure safer feed.

“There was a time my staff forgot to close the pen, and the snails crawled away. We had to start picking them back at night,” he said.

“In 2019, my snails were dying in hundreds. There were days we would record mortalities as high as 800. I tried to troubleshoot and asked for the farm records to check what the snails were feeding on.

“My mind instantly went to the fruits. We used to give them fruits like watermelon. One day, I went to buy watermelon, and the seller told me that most people inject substances to make their fruits red. That was how I discovered what was killing the snails. We stopped buying fruits and decided to plant our own instead.”

The agripreneur noted that he also faces hurdles when exporting his processed snails, as the policies of some countries often cause delays that leave his products spoiled before reaching their destinations.

He noted that his company would require more funding and manpower development to effectively tackle these challenges.

He explained that the farm is launching a programme to train young agriculture graduates in snail farming so that after six months, the trainees will be certified as experts and referred to farms for management roles.

According to him, funding will not only help build infrastructure but also create a conducive learning environment and scale up operations.

“Funding and human resources are our major challenges,” he added.

For Olajumoke, CHASOFF is more than just another farm product; it is proof that Nigerian agriculture can be innovative and sustainable.