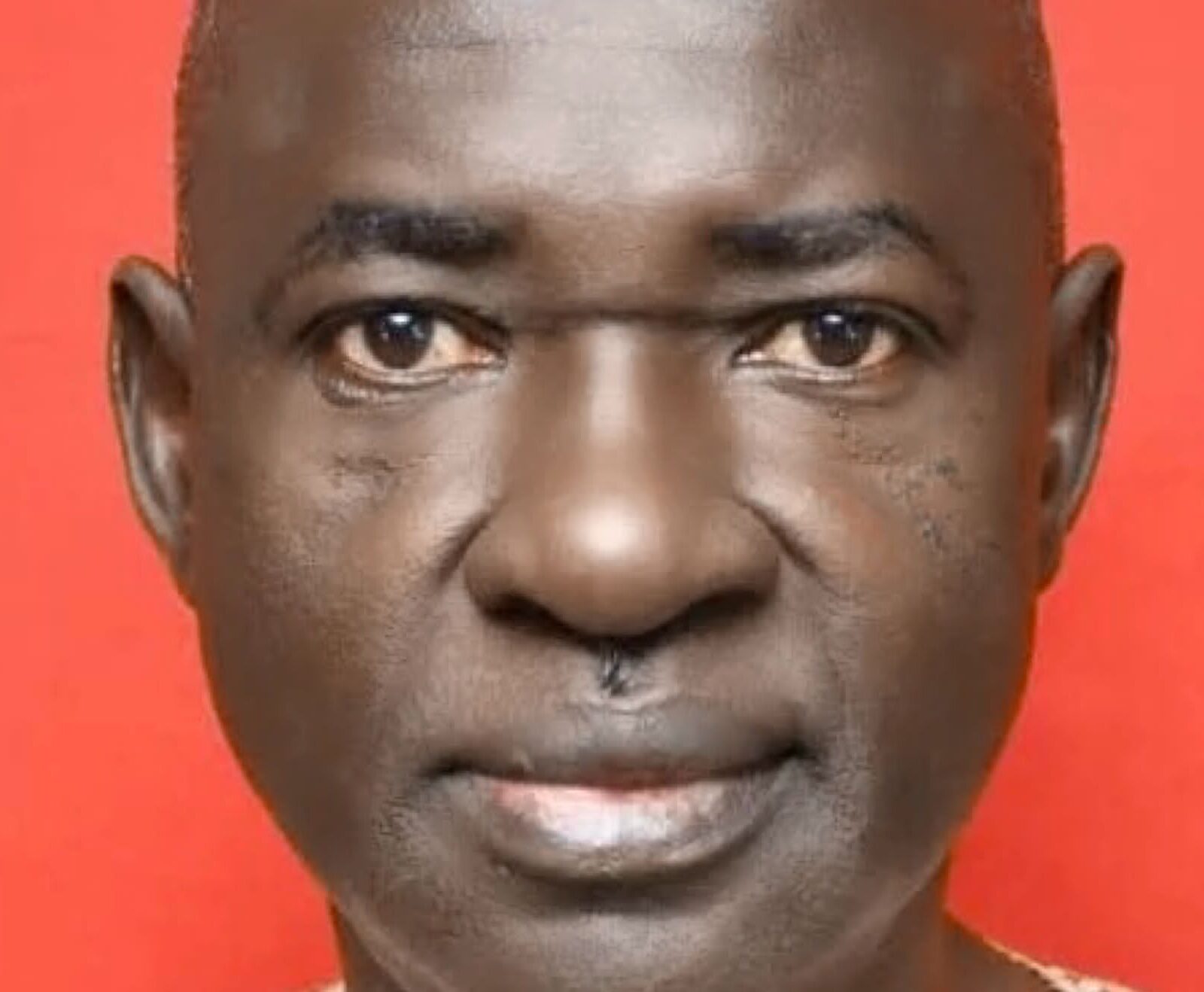

President Bola Tinubu at the Democracy Day celebration in 2024

First, an anecdote. One of my children was born exactly 25 years ago. When I broke the news to a wife of the late Bashorun Moshood Kashimawo Abiola, she was so elated about the coincidence that she started calling him “my June 12 boy” but was shocked when I objected to that nickname. “He was born on the 12th of June, not June 12”, I insisted. For me, then and now, the connotations of the date when the acclaimed fairest and freest presidential election was held in 1993 aren’t completely positive. Yes, it did reveal the capacity of Nigerians to ignore their primordial differences and speak with one voice through an overwhelming majority. It also showed their ability to rise against common enemies, as typified by the military junta that had held the reins of power for long, and be triumphant. All the same, the raw fact of that moment was the scuttling of the general will by a privileged, powerful few. I wasn’t comfortable with my first son being defined by that huge but aborted victory.

Today, June 12, 1993 has earned an enviable position in Nigeria’s history for good. Looking back, the government of the last military Head of State, General Abdulsalami Abubakar, could easily have handed over to that of President Olusegun Obasanjo on June 12, 1999, instead of May 29 that year which was only two weeks earlier to, at least, recognise the symbolism of the electoral revolution that had occurred six years before. One ready alibi though was the cacophony which followed that unfortunate annulment. The divisions and diverse interpretations about the events were so sharp that putting the episodes behind and forging ahead became preoccupations of most segments of the country. Somehow, President Muhammadu Buhari’s decision to replace May 29 with June 12 as Democracy Day has laid to rest arguments about the proper time to commemorate our hard-won fight for representative government.

Thankfully, we’ve recorded 26 unbroken years of civilian administrations – the longest republic since independence. For the younger generation who didn’t witness the excesses of soldiers in government, this record could easily be brushed aside. But those who did would not exchange their freedoms for anything. There was a certain nationalism or patriotism that swept the nation in those days which dwarfed divisive elements like region, religion and ethnicity. The Nigerian people were unanimous about their quest for liberty and nothing was going to stop them. Even when the nullification pronouncement of General Ibrahim Babangida did, the spontaneous reactions across the federation were shock, defiance and calls to announce the results. It was when vacuum was created by Abiola’s escape abroad and time started drifting away that weariness and survival blues set in.

The credit for that feat can neither be claimed nor appropriated by any single person or group. It belongs to the generality of Nigerians and the outsiders who stood by the country in those trying times. The truncation of that historic electoral process and also the eventual return to democracy will forever remain integral parts of the nation’s political records mainly because they were truly momentous. Recent attempts by some topmost actors in the fiasco to exonerate themselves validate this conclusion. Babangida did so through his biography which sought to pass the responsibility to the late General Sani Abacha whose government it was that jailed Abiola after he declared himself president and insisted on actualising his mandate. And only few days ago, Abacha’s widow, Maryam, vehemently rejected Babangida’s claim. It’s clear that no one wants to be on the wrong side of posterity as June 12 will always be a reminder of the era when the collective determination of the people to embrace Abiola’s electioneering mantra of “Hope ‘93” was neutralised.

Advertisement

That hope and the “Renewed Hope” that’s supposed to describe the present lap of our journey on democracy’s highway don’t possess the same energies, sadly. It’s easy to blame the discrepancies between the two captions on the times that have changed and the fact that the dramatis personae have most probably undergone some metamorphosis of their own. Some of them are still active in politics. Whatever those changes may be, they’re fast moving the nation away from democratic ideals, the sorts that made June 12 tick. Democracy, as if we need to be reminded, is that system of government that enables the voices of the populace to, at least, matter and be heard where policies, programmes and projects are designed and executed.

Unfortunately, however, especially beginning from Buhari’s second term in office, the people’s overall participation in the actual processes of governance has been in decline. This condition is directly traceable to a legislature perceived to be weak compared to its predecessors. Leaders of the National Assembly now display servitude and subservience to President Bola Tinubu openly. There are better ways to communicate the willingness of the legislators to collaborate with the executive arm of government to serve the nation than open shows of inferiority and ridiculous genuflections.

Nigeria certainly deserves a more mature, purposeful law-making machinery where oversight functions are not compromised and the wishes and needs of the masses are always in view. As things stand, however, perhaps only providence can save Nigerians from the current arrangement that serves them much less than anticipated at the dawn of this dispensation. Last year on this page, I wrote a piece titled “Reviving a Wearied Citizenry” to mark 25 years of the country’s Fourth Republic. It partly reads: “No formal surveys are needed to determine how disillusioned many Nigerians have become with the affairs of the country. There is hardly any sector that is protected from the forces of retrogression, retardation or defeat.

Advertisement

“Very religion-conscious, most Nigerian citizens are quick to saddle God with the same challenges that he has already given them the abilities to solve. Elections, for instance. The persons and organisations involved in their prosecution, though aware of the centrality of polls to democracy, often fail to demonstrate commensurate commitment before, during and after the exercises. The populace also sometimes undermines them through compromises that can only yield fleeting satisfaction. The result of this socio-political disequilibrium is a situation in which the blames for the nation’s current gross underperformance are multidimensional.”

This despicable state of the chunk of the population hasn’t changed since then, regrettably. Instead, the citizens watch helplessly as politicians act with audacity and impunity. They’re moving in droves from their rival platforms into the ruling party on the pretext that they are fleeing sinking ships; as if they expect aliens to fix them. At best, an average member of the Nigerian political class is a trader (that’s if you’re kind enough not to call him/her a prostitute), a transaction-freak whose actions are guided primarily by the dictates of the belly. Hinging the defections on principles or the common good is simply a story told to marines. It just doesn’t add up.

The constitution that was prepared while Abacha plotted his transmutation to a democratic leader can’t be a genuine popular document. The men who have so far run the affairs of Nigeria since 1999 have, therefore, done so in the shadows of militarism. But even with all the frailties of the earlier legislatures and judiciaries, some form of stability was achieved. Now, the institutions that should provide adequate checks and balance appear too spineless for this critical feature of democracy. We must remember that prices, including the ultimate one, were paid for what is now being turned into a bad dream. The civil society, whatever is left of the opposition, men and women of conscience, and other stakeholders should be on guard. For, civilian authoritarianism can indeed be worse than the dictatorship we overcame at the dusk of the last century.

Ekpe, PhD, is a member of THISDAY editorial board.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.