BY PRUDENCE EMUDIANUGHE

In Nigeria, where therapy is still widely regarded as a luxury, an unlikely form of support is stepping in. AI-powered chatbots like ChatGPT, Replika, and locally developed WhatsApp bots are quietly changing the way young Nigerians navigate everyday emotional distress.

What began as a tool for productivity and homework help is now doubling as a late-night confidant, offering anonymity, immediacy, and something many can’t access in real life: a non-judgmental space.

From venting about trauma and logging daily moods to seeking guidance on anxiety, relationship conflict, and depression, these AI companions are becoming a subtle but steady fixture in the country’s evolving mental health landscape.

Advertisement

The need is undeniable. The World Health Organization estimates that roughly 20 million Nigerians, about 20% of the population, live with a mental health condition, yet only 10% receive formal treatment. Cultural stigma and spiritual interpretations frequently deter people from seeking care. In many rural communities, mental illness is still viewed as a form of spiritual attack or moral failure.

A 2020 survey by the African Polling Institute underscores this: 54% of Nigerians believe mental illness is caused by evil spirits, while 23% see it as divine punishment. For many, the first point of help is a church, mosque, or prayer house, not a licensed therapist. Although the repeal of the colonial-era Lunacy Act and the passage of a new Mental Health Act in 2021 marked an important legal shift, implementation remains slow. Mental health receives just around 3% of Nigeria’s entire public health budget, and most professional services are concentrated in urban areas.

Into this widening gap have stepped digital tools, free, always available, and quietly filling a need that the formal system has yet to meet.

Advertisement

HOW AI CHATBOTS ARE USED

Advertisement

When ChatGPT first became accessible in Nigeria toward the end of 2022, it was largely embraced as a practical tool, something that could help students summarise lecture notes, write job applications and optimise code.

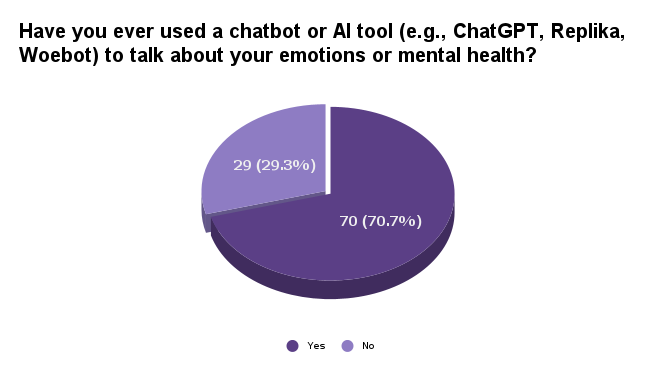

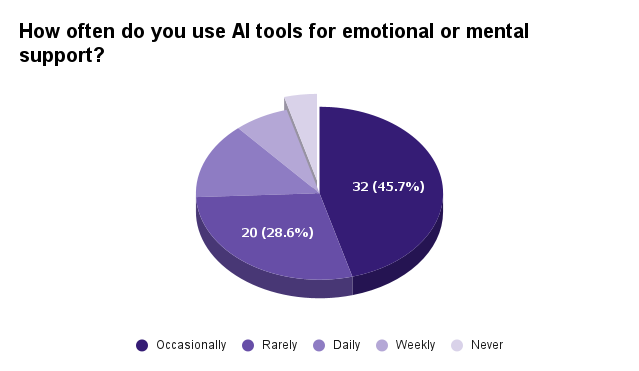

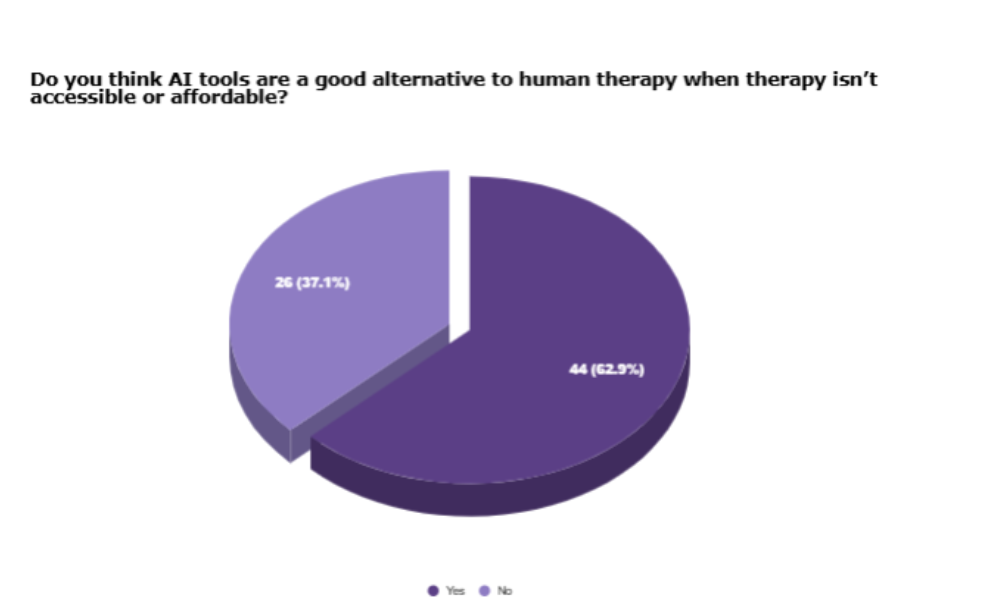

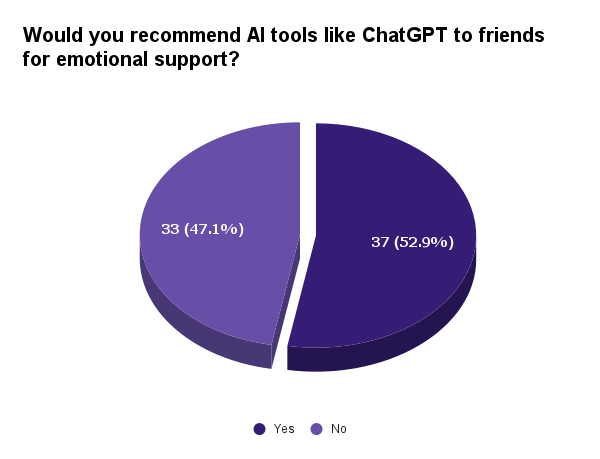

But by early 2024, a quiet shift began to emerge on TikTok, Reddit and WhatsApp forums: users began openly sharing how they were turning to the chatbot not just for productivity, but for emotional companionship. From a survey of around 100 respondents from Nigeria carried out for our report, over 70% have used a chatbot or AI tool to talk about their emotions or mental health.

For many young Nigerians navigating rising unemployment, family pressure and limited access to mental health services, AI tools have become a 24/7 companion, a place to offload emotions in private and without fear of judgement. In these online spaces, even the act of typing becomes a form of release. While some treat it as a stand-in for therapy, others simply see it as a judgment-free zone.

In Nigeria’s expanding tech ecosystem, conversations around AI and mental health are beginning to gain traction, but locally built, fully operational AI mental-health tools remain extremely limited. Platforms like Nguvu Health have taken early steps by integrating lightweight AI features into their teletherapy services, primarily to help triage users before they are connected with licensed therapists.

Advertisement

HerSafeSpace, a women-focused platform, combines digital self-help tools with AI-driven check-ins tailored to survivors of gender-based violence, offering anonymity and safe access to resources in a context where stigma is widespread.

Similarly, SafeSpace Africa has experimented with culturally relevant, chatbot-style support by providing self-help resources and emergency contacts in simple, accessible language for young Africans facing stress, depression, and social stigma. Also, FriendnPal seeks to make emotional support universally available through conversational AI, while also reflecting local realities and cultural sensitivities, with referral systems that guide users to human professionals when needed.

Advertisement

Together, these platforms represent an emerging African approach to digital mental health, blending technology with cultural context and addressing critical gaps in access to care.

Esther Eruchie, founder of Friendnpal, sees AI “supporting with 24/7 access, at all hours you need to talk to somebody, you need a support structure; the AI system is there to help you round the clock. These are things that human therapists cannot do because they are limited, right? Their timing, too, is limited. They have to sleep, they have to eat. But the AI systems are built to help individuals at any time of the day when they need help.”

Advertisement

For Blessing Moses, Founder of BMI Counselling Corner, AI can provide mental-health resources in the moment when someone needs it. For example, if a young person doesn’t have access to a counsellor, AI is there to give the person some structure or direction and to help them stabilise. Some organisations actually use AI to do early screening or first-level crisis response. It can also help simplify information or guide research for people working in mental-health programmes.”

For many young or low-income users with little access to formal care, the need for locally designed, culturally appropriate AI tools is growing rapidly. Esther Eruchie explains, “I believe the first real step toward deeper penetration for mental health solutions in Africa will come when our cultures and traditions begin to shape how these platforms are built. If you can connect with an African in a way that resonates with their lived reality, you don’t need to convince them why the service is valuable; they’ll naturally connect with it. Cultural relevance acts as that bridge.

Advertisement

“For instance, imagine building a mental health app in Nigeria: if the interface speaks in Yoruba while addressing sensitive issues, users are more likely to feel seen and understood. The moment it switches back to English, however, there’s often a gap, an access gap that weakens the sense of connection. This is not unique to mental health; it cuts across healthcare platforms in general. That’s why cultural grounding is not optional for us in Africa; it’s fundamental. We cannot build as though we are westernised, because if our people are to embrace these platforms, they must first recognise themselves in them.”

Most existing solutions are still hybrid in nature, providing basic first-line support and then referring users to human professionals when more specialised help is required.

Religious leaders in Nigeria are increasingly stepping into the AI space, recognising that emotional well-being and spiritual care often overlap. In several churches, AI-generated devotional tools and prayer companions are starting to supplement traditional pastoral counselling.

Apps such as Youversion, Hallow and Abide already use AI to recommend personalised scripture-based meditations and prayer routines, while BibleGPT offers real-time responses to spiritual and emotional questions based on biblical teachings. While none of these tools were developed exclusively in Nigeria, local churches and youth ministries may adapt and contextualise them since spiritual communities are also turning to technology to fill gaps in emotional and mental health support.

According to Yewande Ojo, AI mental health researcher, when it comes to how mental health is categorised, we see different groups of people and different aspects of wellbeing.

“From a cultural and spiritual lens, the question becomes: how do people actually communicate how they feel? Many turn to spiritual or cultural expressions, and the key is making them comfortable enough to share openly,” Ojo said.

“Instead of a one-size-fits-all approach, we shifted the narrative to ‘come as you are, speak to us as you feel.’ This helps us break through cultural and spiritual biases, while recognising that most of the tools we use today are Western in origin and Africans are not Westerners. We feel differently, we express differently. So, building cultural and spiritual realities into mental health support not only improves how people understand their emotions but also how therapists can respond more effectively.”

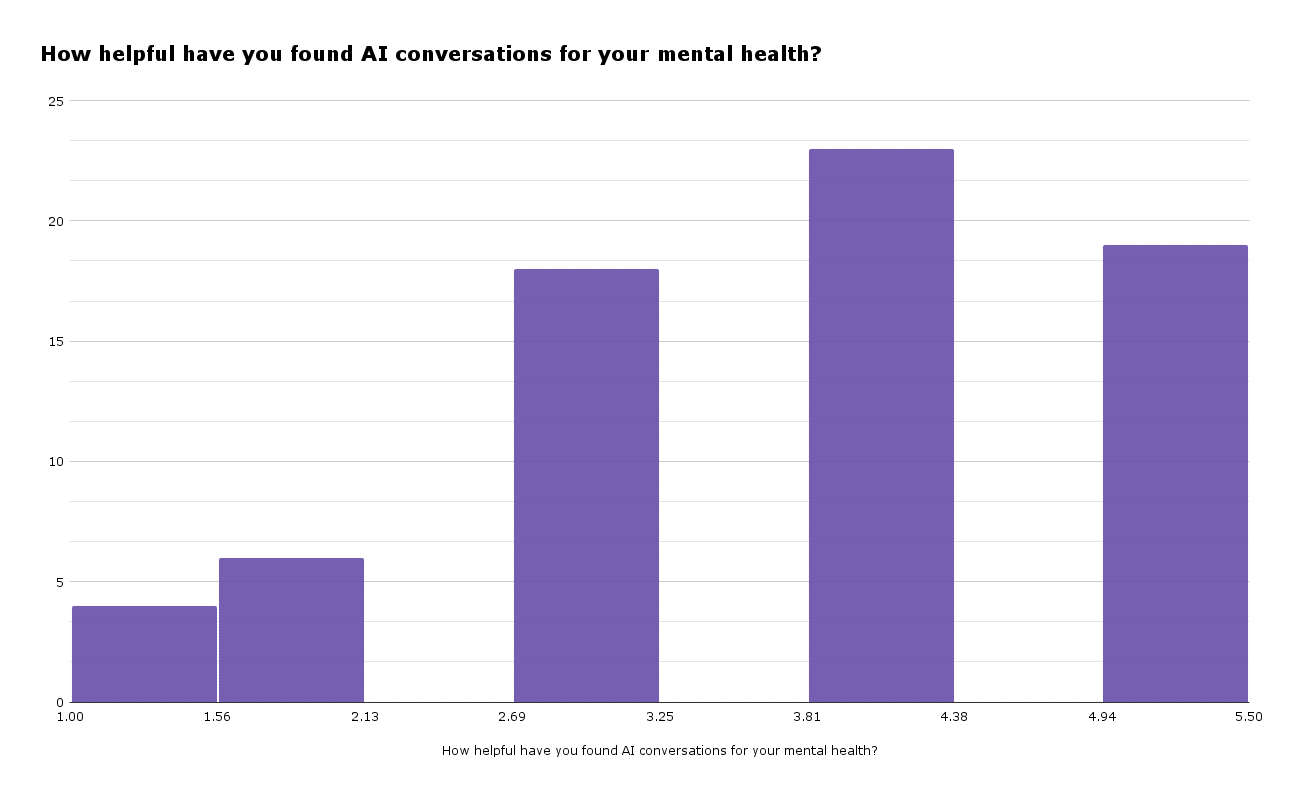

Some young Nigerians say the appeal of AI-based emotional support lies in its immediacy and non-judgmental nature. “I know it’s just a machine, a programmed bot that gives answers based on what it’s been trained on,” they explained. “It’s not like a real therapist who digs deeper or tries to get to the root of the problem.”

Yet they admit that, in moments of acute stress, simply being able to type out their emotions can feel genuinely helpful. “Sometimes the responses aren’t even right, but just getting everything out reduces the pressure. It’s like releasing steam.”

Still, there is rising concern about growing emotional reliance on AI tools. “The problem is, it’s easy to get used to turning to the chatbot every time I feel down,” a user said. “A lot of times it just suggests journaling, when all I really want to do is vent and feel heard.”

Despite those limitations, they credit the tool with helping them build the confidence to express how they feel. “It’s like a handy go-to companion, but I do worry that people might start to think it can replace real human help.”

Mental-health specialists echo this concern, noting that while AI can create a low-barrier “safe space”. It should be viewed as a bridge to care, not a replacement for it. The stigma in our society doesn’t make you comfortable going to a friend or sibling to say, I’m feeling this way, I just need to let it out. That’s why many people turn to AI; it feels like a safer space. Someone even told me, ‘It knows everything anyway, so why not just reach out?’

“This trend shows that people are truly searching for help, and we need to make that support available without putting them at a disadvantage. But we also have to remind users not to take everything AI says as the absolute truth. The technology is still in its early stages, and while it can offer comfort, it’s not yet at the level where you can trust it fully.” Yewande adds.

Ann Chinazo, a final-year student at the University of Port Harcourt, insists, “I still feel like these AI tools are just robots, and I’m not sure they can really give me any clarity. I also worry a lot about data protection and privacy. That’s why I’ve never tried using them.”

Experts remain divided on whether AI tools are ultimately helpful or potentially harmful in the mental-health space.

“Unlike a closed counselling room, AI conversations may be stored on servers. Users need to understand data privacy risks before engaging,” says Ogozi Zorte, counselling psychologist at the University of Port Harcourt. “Similar to regular mental health check-ups, there should be routine assessments to ensure that users are benefiting and not being harmed. Also, AI tools should be transparent about limitations.”

ETHICAL CONCERNS: WHO’S LISTENING?

While AI tools offer convenience and emotional relief, experts warn that they also introduce serious privacy and safety issues, especially when used as a substitute for formal mental health support.

According to Falade Promise Iseoluwa, cybersecurity expert, “Mental-health apps deal with very sensitive data, yet many aren’t built with the strongest protections. The real risks are in how conversations and logs are stored, often in cloud services that, if poorly secured, can be breached or misconfigured. Beyond hacking, some companies even mine user logs for advertising or share insights with third parties. Users should look out for red flags like vague privacy policies, no end-to-end encryption, excessive permission requests, or apps with no two-factor authentication. If you can’t trace the developers or they ask for blanket access to your files and contacts, that’s a clear red flag.”

Most commercially available chatbots, including free versions of ChatGPT and Gemini, do not provide end-to-end encryption. This means that deeply personal conversations are stored on external servers and may be subject to data breaches, company use for training purposes, or third-party access. In a country where mental illness is still heavily stigmatised, that alone creates a significant deterrent.

Equally troubling is the lack of regulation around how these platforms provide mental-health-related advice. Unlike licensed therapists, AI systems are not required to follow duty-of-care standards, nor are they trained to detect the signs of suicidal intent or complex trauma. We’re basically outsourcing emotional care to unregulated systems.

Researchers have also found that chatbots can unintentionally reinforce negative cognitive patterns, for example, by mirroring a user’s pessimistic language or offering inaccurate advice in crisis situations. In extreme cases, users may interpret poorly-worded responses as validation of harmful thoughts, further delaying the decision to seek professional help.

In short, the same tools that offer a safe space can easily become a false sense of safety. “It cannot walk you through the journey. So, yes, people may accept it to some level, but many will also resist it once they realise that they are basically talking to a robot,” adds Ogozi Zorte.

Nigeria still urgently needs better funding for public mental health services and more trained users with caution, especially in a regulatory vacuum.

Even the most optimistic mental-health professionals caution that conversational AI should never be viewed as treatment in itself. At best, they say, it functions as emotional first aid useful for regulating distress in the moment, but fundamentally incapable of replacing the kind of long-term, human-to-human support that real healing often requires.

“AI chatbots cannot provide the same interactive depth as a human counsellor”, says psychologist Ogozi Zorte. “A chatbot could serve as an entry point for students, after which they can meet a counsellor if needed. But safeguards must be in place to ensure quality, safety, and privacy. There’s a need to evaluate the pros and cons of AI tools and weigh them against the benefits of traditional counselling. Then they can make an informed choice.”

According to Chisom Muoma, a practising guidance counsellor, the danger lies not in the technology itself, but in what might be neglected if it becomes the default option.

“AI chatbots can be accepted, and they can actually help young people. But you will also have a lot of resistance. The truth is that chatbots do not have feelings. They do not have empathy, and that is the bedrock of counselling. Non-verbal cues, emotional presence, and reading a person’s tone and posture. AI cannot do that. It can follow prompts and give tips or clinicians and community-level education that reduces stigma and normalises help-seeking. Without those foundational systems in place, AI risks becoming a digital bandage over a much deeper wound,” Muoma said.

THE WAY FORWARD

AI’s evolving role in Nigeria’s mental-health landscape is less about technology and more about demand.

According to Yewande Ojo, “The future of digital mental health in Africa is a beautiful one. With more people gaining access to phones and the internet, the basic requirements for digital support, mental health care will increasingly become more available. As connectivity expands and resources improve, digital mental health will keep growing. Africans have already shown openness in embracing these technologies, and that’s the most important first step.”

Young Nigerians are clearly asking for support, and where institutions fail to meet that need, they are turning to whatever is available, even if that means confiding in a chatbot at 2 a.m. The rise of digital mental-health tools is therefore not just a technological trend, but a social signal.

To harness their potential without creating new harms, Nigeria now needs to respond by building public education that encourages help-seeking and reduces stigma, ethical and regulatory safeguards for AI-based tools, and culturally grounded design that reflects the lived realities of Nigerian users.

AI may never replace human care, but in a country where so many face emotional distress with nowhere to turn, it may serve as a critical first step. Until the mental-health system catches up, digital tools may function not as a cure, but as a much-needed oasis in an otherwise dry and neglected landscape.

And as Esther Eruchie concludes about AI’s roles in the Mental health landscape, “It’s also going to help expedite advocacy, because you’re not just raising awareness anymore, people are actually able to access solutions faster. With AI, there’s the added layer of personalisation: users don’t just get generic support, they get care that feels tailored to them, their context, and their needs.

That’s powerful, especially in Africa, where cultural relevance matters so much. AI makes mental health support more accessible, more personal, and more comfortable, all from the privacy and safety of one’s home.” A kind of shift that turns advocacy into action.

This report was produced with support from the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) and Luminate.