BY OKEY IKECHUKWU

This is the central message of this book: The transfer of private sector skills to drive efficiency in the public sector is possible. It is a good thing actually, because it will lead to better leadership, improved service delivery and a more responsive and responsible public sector. But there are challenges at three distinct levels. The first is that of determining the contextual deployment of the skills, in terms of tactics adopted by the leader. The second is that of navigating the treacherous terrain and landmines of entrenched interests in the public sector. The third is that of ensuring that one does not abandon one’s core values on the altar of expediency.

The questions I see the author asking here are: (1) How do you move from preachment to practice, from promise to performance and from idealism to hands-on realism without sacrificing who you are and what you stand for? (2) How do you navigate the pressures of the moment? (3) How do you correctly determine what sacrifices to make, while retaining your authenticity and Brand integrity?

This book submits that the danger posed by the ever-present threat of being ambushed by realities never anticipated, the disconnect sometimes created by idealism and limited political exposure, is real. This submission is also at the heart of all existentialist thinking and existentialist philosophy. It is the fundament of the French philosopher, Jean Paul Satre’s thesis that human beings are not defined by what they say, what they are taught, or what they claim to believe; but by what they live and act out on a daily basis.

Advertisement

A young lady who is well behaved at home, circumscribed by parental rules and a regular routine, and who does not go anywhere exciting, continues to live her life as a quiet and responsible girl. Then she enters the university. Lo and behold, it is not the same person anymore. The story is the same for many moral crusaders and disciples of good governance who perform disastrously when given a chance in public office.

Thus, if we are defined more by our behaviour in the face of real challenges than by what we preach, it must follow that only those who have gone into the storm, weathered the storm and returned from the storm can be said to possess Brand Integrity.

It is this existential conundrum that Waziri Adio placed before us in his book; with himself as the guinea pig that ventured out and returned alive; even if panting and astonished at the dangers out there. With him, as presented in this book, one fact is clear about how to hold office and still be yourself. That fact is that anyone can collapse before the pressures of the moment, or succeed and come out standing tall, depending on how he navigates the operating environment. Yes, and it means to always be aware of, and struggle not to lose sight of, one’s core values. The other point, of course, is to keep the right objectives in view; in terms of long-term sustainable leadership goals and the overall objectives of public office.

Advertisement

A strong element of the author’s submissions is that executive capacity, administrative efficiency and adherence to rules, are necessary but not sufficient conditions for leadership success. Yes, they are critical success factors for leadership, but he warns us that it is not a smooth ride, with cheerleaders on both sides of the isle! He admits that these valued qualities, which are often attributed to people we loosely call technocrats (whatever that means), can be brought to bear on the public sector for greater service delivery.

He notes that the machinery and processes for adding value to the public sector through such capacities exist. But he then warns us that the public sector is a minefield of warped values, a slippery terrain, probably also a wild forest full of falling trees, poisonous snakes, crocodiles, quicksand and nasty spiders. We also see through his lenses that a leader who is not alert will get mired in questionable practices, arbitrary exercise of executive discretion, unconscionable demands and expectations, as well as a well-established culture of questionable excesses and privileges.

ADDRESS TO TECHNOCRATS:

This book, in part and as a whole, should be a manual for all who call themselves technocrats, patriots, well-meaning Nigerians, social critics and public affairs analysts. It offers a clear object lesson: on the need for this category of persons to be eternally watchful of their views, presumptions and assumptions about what it takes to lead with positive values and succeed in the public sector. One who achieves leadership and administrative efficiency and success, but sacrifices one’s core values, is a failure. It is through unremitting hands-on experience, amidst great moral and other dangers, that one who is truly accomplished in a strictly rule-governed environment can transmute into a success story in the public sector. The author shares his personal experiences and challenges; simultaneously showing us how one can succeed and be oneself, despite all odds.

Advertisement

Let our technocrats, and that noisy breed of speech makers who mistake pontification for capacity to lead, use this book, The Arc of the Possible, as a reality check. That is for those of them who wish to understand the conflict between the desire to make change happen and the ability to do so. The book reveals the limits of idealism. It shows the reader that it is not luck, or Holy Ghost fire, that leads to success for one who swims against the currents in a fundamentally corrupt society. This is doubly so when the society in question is managed by a leadership elite that is focused on consumption.

What is most heart-warming here is that The Arc of the Possible is the testimony, or testimonial, of someone who has gone, engaged, navigated dangerous waters, and is saying: “Hey, it is possible! Rather than just step out satisfied with his widely acclaimed victory, or organize a grand party to be praised by guests who will repetitively reel out his achievements until everyone is bored to death, the author felt duty-bound, as he held his head above water, to call out to those still on the beach; to share his experiences and to alert them about the areas with deep waters and strong currents.

As relayed in this book, the author’s approach to issues and his actions as chief executive, stand in sharp contrast to those of most or our elected leaders, especially governors, and heads of government agencies. These people have become experts in what I call incestuous communication and leadership by self-deception. Just look at this scenario (1) Somebody commissions a documentary at an inflated cost. (2) The same person ensures that a nice story is written. (3) The same person, through his proxies, vets the story, while pretending that it is being told by someone else. (4) The story is about everything he would like to hear about himself and his watch. (5) Everything he does not what to hear or know must be excluded. (6) Then he pays for airtime, in order to have it shown on major television stations, on the BBC, CNN, or Aljazeera.

Tell me, ladies and gentlemen, besides the governor/chief executive and those specially gathered to watch this in selected sitting rooms and shouting in sycophantic self-diminution, who else is really interested in this story? Is it the civil servants who produced the documentary and who are in their houses at the time the documentary is being aired? And, do not forget, those who produced that documentary have produced similar documentaries for at least three governors or chief executives before the current one. Nearly all the impressive strides in service delivery, or social infrastructure, education and health exist only in the imagination of the CEO and in the documentary.

Advertisement

Tell me, ladies and gentlemen, where are all the books written about the fantastic achievements of our past military and civilian governors? Who read any of them, including those who tremblingly received copies autographed in executive red ink by the lords of the hour? The truth is that we are not learning well, and we are not learning fast enough. Otherwise the regular charade of 100 days in office by our leaders, the scandalous publication of painted schools and hospitals, especially in places where school enrolment, academic performance, number of WAEC and JAMB candidates, health services, doctors and nurses are abysmally low, would have stopped long before now.

A Necessary Confession:

Advertisement

Let me make a confession at this point, before I go on to conclude this book review. The confession is that I am here reviewing a book which I had thought I would write myself. It is because of Waziri’s restless pen that I am not the author of a book about someone who, like Olusegun Adeniyi, Ifueko Omoigui-Okaru and others I have long been convinced should be held up to the people as examples for Nigerian youths to follow, if they want lasting values and leadership success. Though I ordinarily do not write biographies as a rule, I set out to do a joint biography of Segun and Waziri and finish it before my birthday of 30th September, which I had set as deadline for myself regarding certain types of endeavours. Waziri, who is obviously hearing this for the first time, dropped from my list when I read in the papers that he was almost done with his book.

As for Segun, you needed to have seen the shock on his face when I told him that I wanted to write a book about him. In fact, he had immediately said, very casually: “Ah ok, what is the book about,” before it hit him. The next thing was: “Wait, what, how, I mean what is there to write about me?” Next he asked whether that was why I requested that we met in the office. When I answered in the affirmative, he assured me that there was nothing to write about him and that I should instead think of people who should write about me.

Advertisement

I explained my reasons, his background, his resilience and diligence, how he has always been described as reliable by everyone he has ever dealt with. I reminded him of the joint youth programmes, including the one we had on parenting and mentoring for busy people. I pointed out that his biography, written by me, will be taken seriously since no one will say that he paid for it. We parted that day on the understanding that he did not ask for it that young Nigerians need to see the right role models and not think that it is only political office holders that people write about. Ladies and gentlemen, I invite you as my witnesses that Segun has allowed my September birthday to pass, so blame him and not me.

From Waziri Adio to His Book

Advertisement

Going back to The Arc of the Possible, let us recall that the author was a renowned writer and critic, both of policy and of the conduct of people in public office, before his just-concluded watch at NEITI. He had, in some measure, acquired a reputation as a “technocrat” over the years. His book is, first and foremost, a memoir. But it is also a written documentary about a hands-on encounter with the challenges of moving from the position of a voluble, even if informed, analyst and critic to an active participant who is forced to learn more about himself and about the dynamics of a warped value system.

The book also gives us templates which, if applied, can help those who refuse to forget who they are to survive unscathed. Above all, it takes the reader from where we are today in leadership and public office management to the qualities of character, as well as processes and paradigms we need if we are to create and sustain a 21st century nation.

As part commentary, part reflection and part sub-thesis on the political economy of the Nigerian State, The Arc of the possible is a work that could also have been alternatively titled: Profile of a Tenure. This is what the author has to say after his watch at NEITI: “…I am proud of the little we were able to achieve, I am prouder of my ability to remain myself, my refusal to get sucked into the grandeur and permissiveness that we weave around public office in Nigeria, the conscious decision to uphold, largely through myself, the values I hold dear.”

This book, which details this experience, is in five main parts. These five sections are thematically grouped to capture and address related issues. Each part is made up of several chapters and we have a total of 25 chapters in all. This is followed by an epilogue, an acknowledgements and an index.

I would like to start on the structure of the book by commending the author for putting the acknowledgement at the end of the book. It is certainly unconventional, but that is the author being himself. As a person who has practically no regard whatsoever for presumably impregnable conventions, knowing that most conventions have dated validity, I specially commend Waziri for sparing me (I don’t know about others) the sometimes sycophantic and off-putting long acknowledgement section that you find at the beginning of most books and biographies. Is it ingratitude on the author’s part? Is it presumption? Is it the author’s sense of the dramatic? Was it, perhaps, an error by the printer? Most probably not. But whatever may be the reason for the position of the acknowledgment, I love it where it is.

The first part of the book, titled ‘The Path to Public Life,’ which is made up of two chapters, gives us the circumstance of the author’s emergence as the Executive Secretary of NEITI. We got to know the persons involved in making the appointment possible and the author’s initial reactions and impressions. This section also brings out in beautiful prose about how the author’s stint as Adviser to the Senate President can be described as a Dress and Tech rehearsal for public office. This section also brought out, in particular, the commendable disposition of the Chairman of the THISDAY stable regarding the fate and fortunes of his people.

The second part, titled “Building Blocks,” and which is made up of seven chapters, starts with a historical and process review of the organization, NEITI. It showed the author’s clear grasp of the agency and also of his mandate. His initial experiences as CEO, the initial success stories, the successful on-boarding of high-end personnel, the pivotal role of strategy in organizational success and health check tools he deployed. This section also brought us face-to-face with the role, power and significance of strategy and attention to detail as a performance driver. The imperative of a leader sending out the right signals and how Waziri’s signalling, captured under the gingerly and clearly mischievous title “A Toe in the Water” ended without the toe being bitten off. In his own words: “It came good and validated the value of trying to do things differently, or being entrepreneurial, and of seeking to make things happen rather than just trusting that they would happen by themselves.”

Part three of the book, which has eight chapters, is titled “Getting things Done.” It brings out the game-changing role of policy papers. It speaks of “How the policy and strategy work-stream pivoted on its own strategic sequence: generating compelling and stylized evidence, following it up with direct engagement, and leveraging the two to generate the desired action.” Drawing from the above, this section x-rays the virtues of evidence-led and impact-driven advocacy, how NEITI navigated the PSC amendment jinx and what the author considers “…the most important achievement of NEITI” under his watch. Go and read this section if you want to know how timelier and cheaper audit reports helped NEITI under the author, how technology is leveraged for impact and efficiency, and how NEITI under the author unveiled “…a publicly accessible register of beneficial owners of some extractive assets in Nigeria.” It reveals how donor trust and support grew and how, hitherto adversarial, or at least cold, relations improved between the NNPC and NEITI.

Part four, titled “The Value of Values,” with its four chapters, is the soul of much of what the author set out to say in this book. Waziri Adio’s core personal values, which impacted his work ethic and which can also be gleaned from all his reflexes as Executive Secretary of NEITI, manifested from the first day he appeared as CEO. He refused to have a special photographer take his “official” portrait, to be hung in his office. Thus, he had no official photograph in the place for the five years he was Executive Secretary of NEITI. He also refused to have his simple request for an official laptop to morph into a memo asking him to approve for himself a laptop, an iPad and an iPhone, which he never asked for.

He rejected the explanation that it was “… the standard for the ES and other members of the senior management staff to have official phones and tablets.” When he was told: “The tablet is for when you go outside for a meeting or you are on the road, and you may need to access your email or some important documents” he replied: “But I can do all of that on my phone.” Going further, he said: “I don’t need an official phone. My phone is a dual-SIM one. So, either I return to carrying two handsets or I give out the iPhone. I don’t think that is a good way to spend public money.”

This reported exchange between the author and NEITI administrative personnel reminds me of some of Peter Obi’s narratives. As the young Chairman of a bank, Peter Obi discovered that a new Mercedes 500 limousine had been bought for him to use whenever he can for board meetings. He asked them how many times such a meeting would hold in a year and then directed that the vehicle be sold off and the money put in the coffers of the bank. He assured his confounded senior managers that people whose job is to keep and manage other people’s money in trust should not be seen living ostentatious lives. He also got rid of the Chairman’s guest house, since he lived in Lagos. When he found out that the bank’s top management travelled first class overseas, he demanded an explanation. When he was told that the first class compartment was the likely place for them to meet high net worth clients, he wanted to know how many such clients any of them had met in the First Class compartment in the last ten year. The answer was “none.” That was the end of first class trips for the banking executives in his bank. But we are digressing.

Back to The Arc of the Possible and the memo designed to make Waziri Adio incur some avoidable expenses in the name of NEITI. He insisted that the memo be taken away and only approved a fresh memo to get himself a laptop. It was this laptop that he used for the five years he was in office. He did not, as he said in the book, use “…getting the work done as an excuse for downgrading the importance of values.”

But did he proceed from this, and similar, incidents to argue that Nigerians are fundamentally immoral people? No, he did not. The author recognizes the challenges posed by personalization of public office and the tendency for some to assume that accountability need not be taken too seriously. But he sees this as what happens anywhere you have weak institutions and executive discretion is given a wide spectrum.

It is on the basis of this understanding that his views on “Leading Through Self” and tackling entitlement mentality can be understood. He urges us to explore and entrench the inspirations around which the new can be anchored. This is to be borne in mind, because “…individual examples are not as useful as system-and society-wide change in reshaping deeply rooted values.”

The last part of this book, Part Five, which is made up of three chapters, is titled “Obstacles and battles.” It speaks to the dire straits in which those who deviate from the norm find themselves in an environment like ours. You need more than a great strategy and good intentions to survive. Tenacity and a refusal to be demoralized comes in handy. Read chapter 22 of this book, titled “Dire Straits” to know about all that. Chapter 23 tells you how an administrative lapse, such as not putting rent on the budget, can ungird much in an organization with fiscal challenges. As for the expected reactions, pushbacks and counter actions by persons, groups and interests not benefitting from the new focus of NEITI under the author, this is what the author has to say: “Changing a set culture within an organization or in the larger environment is some piece of work which can defeat even the most adept and determined administrator.”

The Question of Objectivity

Can the book before us today be described as an objective narrative, especially bearing in mind that it is an individual’s interpretation of experiences that are coloured by who he is, his core values and his inclinations? When we speak of objectivity in communication and discourse generally, we often hear the rather uninterrogated claims of journalists, namely, “Facts are sacred. Opinion is free.” I disagreed with this statement. All the facts of our daily experience are usually interpreted facts. The interpretative tools are usually physiologically, culturally, religiously and experientially determined. A cell phone is a fact to us, but it is a mystery to a primitive man. Once we make a distinction between “objects of experience, independent of an observer” and “objects of experience as reported by an observer,” we see that the presumed “sacredness” of facts collapse irredeemably.

Concerning opinions, I dare say that opinions are not free at all. No one is free to say whatever he likes, whenever he likes and wherever he likes totally unchallenged. But having said that, how does this short foray into some of the most frightening question of philosophy come into our business of reviewing The Arc of the Possible? Does this then mean that we have no way of making a distinction between what is objective and what it not?

Waziri Adio’s book rests on many verifiable processes, institutional and interactional variables that we can hold unto, to make correct inferences about his submissions. These submissions are, first and foremost, completely in sync with the lived experiences of most of us here; especially people who have held one type of public position, sub public position or the other. His insights, observations and suggestions agree with the position of many reputed scholars on the sociology and dynamics of transformational leadership in a morally unstructured environment.

Without denying that an interpreter of human experience, or his tools, may be faulty, we note with relief that the author’s conclusions and inferences in The Arc of the Possible derive from, and are largely warranted by, the preceding and related narratives. Thus, using the concept of objectivity in terms of the extent to which the book is largely relatable-experience based, we can describe it as an objective account of the issues under reference. It retains a very respectable profile as a report, as a series of reflections, as a written documentary and commentary on government and as a case study of the governance challenges we must navigate successfully if we are to build a viable and lasting Nigerian state. The book is at once didactic, biographical and historical, because the author drew conclusions about lived and really trying experiences, while struggling to be faithful to the facts as he sees them.

Other comments and Observations

The major comment here is that The Arc of the Possible should not become one of those book that only the author would talk about. Like Olusegun Adeniyi’s book, From Frying Pan to Fire, on illegal migration which should be made compulsory literature in secondary schools, Waziri Adio’s book should be on a must read in ASCON, NIPPS, Faculties of Management and high-end human capital development and leadership platforms and institutions. It will be an invaluable resource for scholars, leaders and students of leadership and existentialist thinking.

The other point is to say that the author should see his tenure at NEITI as a rehearsal for future, much more demanding, leadership positions.

The editorial and technical quality of the book is almost flawless. This is a lasting tribute to the editors and publishers. This is hardly surprising, knowing that Simon Kolawole is involved, with Olusegun Adeniyi as brother and imperator to the author.

As I congratulate the author and publishers, let me place it on record that, based on this book, including the testimonies of third parties and stakeholders in the industry under reference in this work, the author, Waziri Adio retained his Brand Integrity.

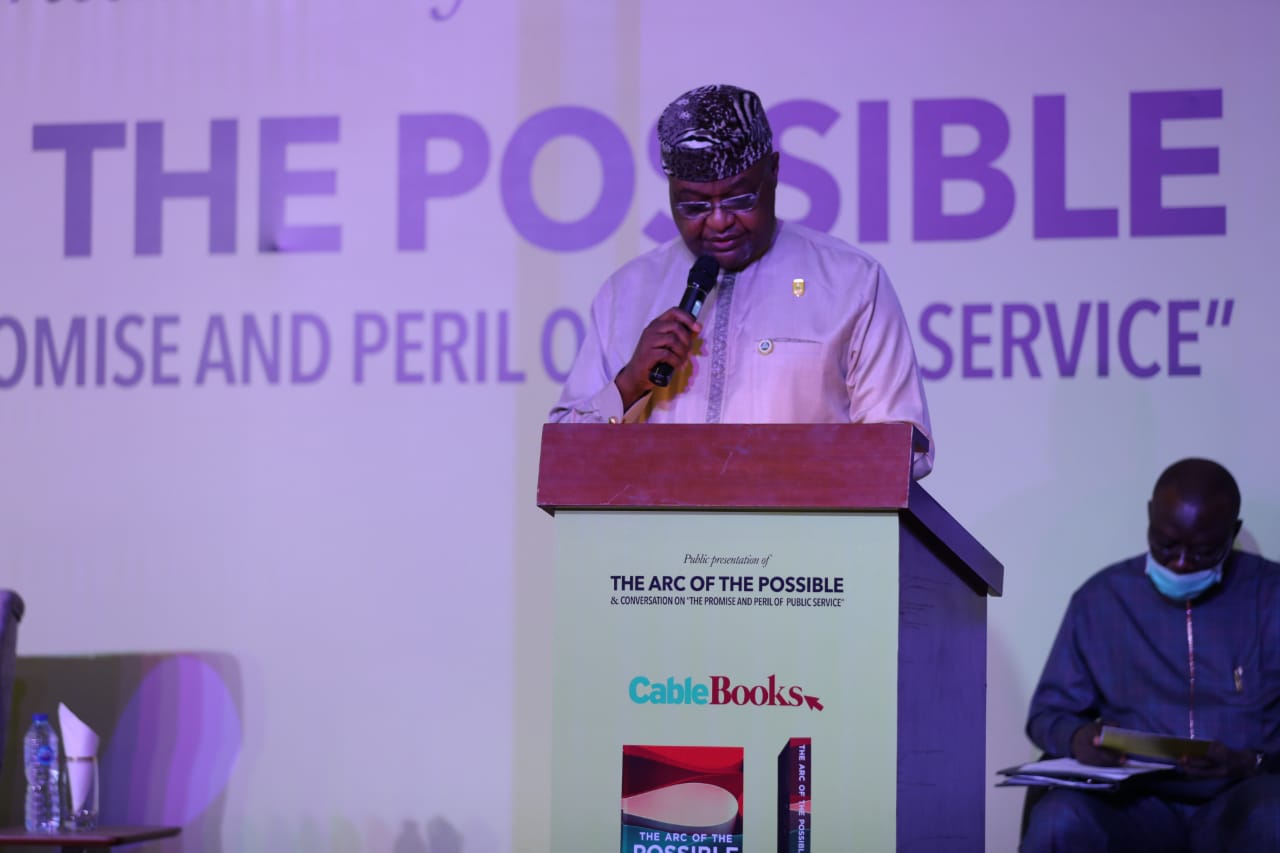

Text of the book review by Dr Okey Ikechukwu, mni, at the public presentation of Waziri Adio’s book, ‘The Arc of the Possible’ in Abuja on Saturday, December 11, 2021

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.