BY VICTOR TERHEMBA

In recent Nigeria, money is no longer just a means of economic exchange or a measure of value for it has evolved into a totalizing force, an arbiter of human relevance. It determines not only what individuals can afford, but what they are allowed to aspire to, how seriously they are taken, and even how morally they are judged.

Money has become the metric through which Nigerians are evaluated, categorized, and either elevated or dismissed. It governs not just actions, but perceptions; not just outcomes, but worthiness. This is a society where the question “How much is he worth?” has been emptied of moral or intellectual meaning. It no longer refers to one’s contribution to the community, depth of insight, or the richness of one’s life experience. Instead, it is a literal question: “How much money does he have?” For in this new order, poverty is not merely a misfortune, it is a stigma, a moral failing, a scarlet letter worn by the economically disenfranchised. To be poor is to be invisible, disrespected, and often treated as undeserving of dignity or voice.

Wealth, on the other hand, regardless of provenance, is revered with an almost spiritual fervor. The nouveau riche are celebrated without scrutiny; the self-made (or seemingly self-made) are canonized as heroes. No one asks how the money was made; the possession of it alone is proof of success, even genius. Wealth is treated not as an outcome of labor or enterprise, but as a sign of personal virtue and divine favor. In this sense, it has not just been commodified, but theologized that money is now a kind of secular salvation.

Advertisement

It is important to recognize that the Nigerian fascination with wealth is not new. Historically, wealth has always commanded respect across cultures. But the current moment represents something far more profound: a civilizational shift where money has supplanted every other standard by which we judge right and wrong, noble and base, admirable and condemnable. It has become the nucleus of personal identity, the defining characteristic of aspiration, and the sole currency of legitimacy.

This transformation is existential in its implications. A society that builds its moral order around money risks collapsing into a transactional wasteland, where nothing has value unless it has a price, and where no action is too immoral so long as it is profitable. We see this everywhere: in the normalization of “Yahoo Yahoo” (internet fraud) among youth, in the glorification of ostentatious lifestyles on social media, in the quiet approval of shady business practices, and in the celebration of political theft so long as it trickles down in the form of handouts.

Indeed, the moral imagination of the Nigerian society has been hijacked by this insatiable appetite for financial validation. In everyday conversation, one hears chilling refrains like:

“At least he’s making money,”

“Money is all that matters.”

“No one respects you if you’re broke.”

Advertisement

These phrases are not mere idioms; they are cultural truths, spoken with resignation, defended with pride, and lived with desperation. They reflect a broader existential anxiety that encapsulates a fear that without wealth, you have no identity, no status, and no future.

But herein lies the danger: when money becomes the sole determinant of value, values themselves disappear. The society loses its ability to distinguish between greatness and greed, between leadership and looting, between influence and integrity. We breed a generation that aspires not to impact but to impress, not to serve but to shine. And this is not an elite problem alone as it cuts across class, geography, education, and religion. In the streets and in boardrooms, in mosques and churches, in campuses and marketplaces, the drumbeat of materialism drowns out the quiet voice of conscience. The pastor who preaches prosperity over piety is not an aberration, he is a mirror. The youth who dreams of riches without labor is not misguided, he is a product.

But perhaps more corrosive than the idolization of wealth is the hatred of poverty—a deeply internalized cultural bias that sees being poor not as the consequence of structural inequality, failed governance, or limited opportunity, but as a moral defect. In Nigeria today, poverty is not merely pitied; it is scorned, mocked, and often despised. It is perceived as a kind of social leprosy, a condition to be hidden or cured at all costs. This criminalization of poverty finds expression not only in the demeaning way the poor are spoken about—”He’s just lazy,” “She doesn’t think smart,” “Why can’t they hustle harder?”—but also in how they are treated by society at large.

Poor people are routinely humiliated at banks, ignored in hospitals, denied dignified housing, and excluded from spaces of influence and decision-making. Even public services that are meant to serve everyone often function as if the poor are an afterthought, if not an outright nuisance. This hostility is systemic, embedded in everything from urban planning to customer service, from how job ads are written to how politicians craft their messaging. It is a society-wide consensus that the poor are not just unfortunate; they are unworthy. And in this warped moral order, poverty becomes not just an economic status, but a social sentence—one that silences, marginalizes, and ultimately erases.

Advertisement

This disdain is not subtle. It is etched into the very infrastructure of the economy. Landlords routinely hike rents beyond the reach of honest workers. Healthcare remains inaccessible unless one can pay in full, in cash, and in advance. Food prices skyrocket weekly. Basic needs like water, power, and shelter are treated as luxuries for the few. All this is in a country where 56% of the population (approximately 129 million people) live below the poverty line, according to the World Bank. A nation with a declining GDP, crumbling productivity, and runaway inflation behaves as if everyone should be rich and that if you’re not, it’s your fault.

Nowhere is this social hostility more visible than on social media. Platforms like Twitter (now X) have become digital coliseums where the poor are not just mocked but dehumanized. Users gleefully dig through others’ timelines to find evidence of participating in past giveaways, using them to discredit opinions and silence dissent. “You can’t speak on national issues—you’re broke,” they imply. In this dystopia, money is not just power; it is voice. And the voiceless are those who dare to speak without wealth. I can recall several incidents where an X user shares an opinion on an issue or criticizes a political figure. Rather than engage the argument, opponents post screenshots of the critic’s past plea for financial assistance on the app. The message is loud and clear: Your poverty disqualifies your perspective. In that moment, it is not the politician who is condemned, but the poor citizen who dares to hope for better.

What we are witnessing is not merely a moral decline but a philosophical inversion, a disturbing upending of what society once held sacred. Where cultures traditionally celebrated integrity, wisdom, sacrifice, and service to others as the hallmarks of a meaningful life, Nigerian society has increasingly surrendered these ideals at the altar of material gain. Wealth is no longer just a reward; it is the only proof of virtue. The crisis is so deep that even the most intimate units of moral instruction which is the family, have not been spared.

In homes across the country, parents now evaluate the success of their children not by the strength of their character or the value of their contributions, but by the size of their income and the flash of their lifestyle. Anecdotes are tragically common: mothers who once wept at the thought of their sons joining criminal gangs now beam with pride at their sudden affluence, never daring to question its source.

Advertisement

Fathers who once emphasized honor now turn a blind eye to dubious business dealings as long as the money flows. What was once feared is now envied; what was once condemned is now quietly blessed. In this climate, moral ambiguity becomes a family secret, and silence becomes complicity. The social contract is no longer based on shared values—it is now secured by the currency of survival and the illusion of success.

This commodification of the soul comes at a cost. It corrodes empathy, fractures community, and destroys the very possibility of collective progress. If every man is only as good as his wallet, then there is no shared destiny, only private pursuits. If values are abandoned for gains, then what remains to hold society together?

Advertisement

The tragedy is not that Nigerians desire wealth because that is a universal instinct and it is understandable, but that in the relentless pursuit of it, so much else has been cast aside: principles, empathy, truth, even community. In this distorted moral economy, where success is measured purely in naira and dollars, poverty is no longer seen as a shared challenge or societal failing but interpreted as a personal disgrace, a sign of inferiority or incompetence. Conversely, money is treated as evidence of intelligence, strength or even divine favour.

This worldview is a fertile ground for the very ills that plague Nigeria. Corruption is now not just tolerated but expected; impunity is normalized because accountability is only for the powerless; and hope, the invisible thread that binds people to possibility and progress, withers under the weight of disillusionment. When money becomes the sole criterion for dignity, justice, and relevance, it strips society of its moral compass and creates a vicious cycle where power is used to accumulate wealth, and wealth is used to escape the consequences of power abused.

Advertisement

Yet, there is still a choice to be made. A society like Nigeria can choose what it worships. It can choose to dignify work, to respect honesty, and to protect the vulnerable. Or it can choose to see poverty not as a crime, but as a challenge to be addressed with justice and solidarity. I have always opined that we must promote the values that we wish to make a change then dwelling on the ills and problems. Until then, we must confront the uncomfortable truth, Nigeria is not just a poor country, it is a country that hates the poor. And until that hatred is undone, no amount of wealth will redeem us.

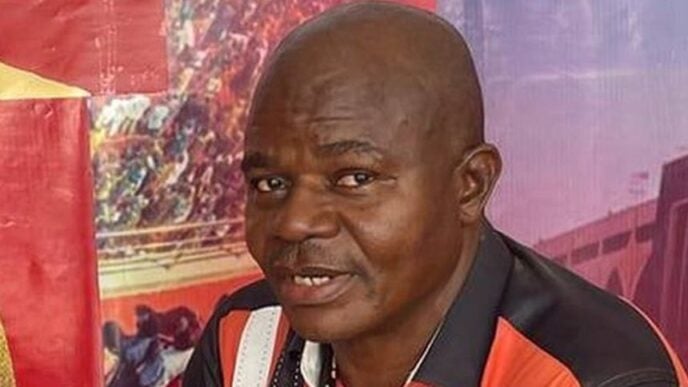

Victor Terhemba is a dedicated development practitioner and democracy advocate with years of experience in advancing Democracy, Youth Participation, Civic Engagement, and Inclusive Governance in Nigeria. He can be reached via [email protected] or on X @Victor_Terhemba.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.