BY TOSIN ADEOTI

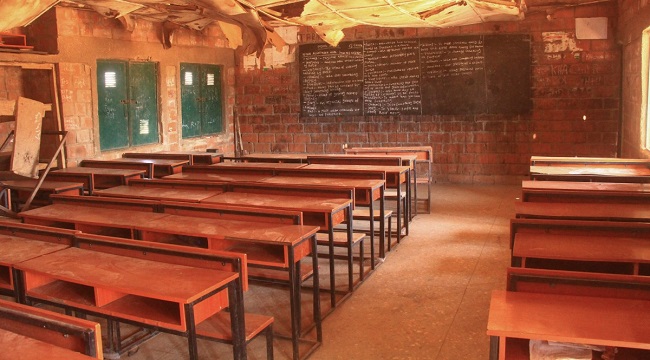

Escalating insecurity has pushed Nigeria into an education crisis that grows wider each week. What began as a cluster of violent incidents in November has now hardened into a wave of school shutdowns that stretches from the Middle Belt to the far North. In a country where millions of children are already out of school, the closures reveal something deeper and more troubling. They show a state that is struggling to protect the fundamental spaces where young people imagine a different future.

In late November, panic spread across communities in Kwara State after gunmen kidnapped worshippers from the Christ Apostolic Church in Eruku. Reports soon emerged that the abductors demanded one hundred million naira per victim. Fear rose sharply among parents, teachers and local leaders. Within hours, the state government ordered an immediate shutdown of schools in four local government areas, namely Isin, Irepodun, Ifelodun and Ekiti. Teachers received the directive through the Nigeria Union of Teachers. Children were sent home in a rush, many of them carrying half-completed assignments and exam schedules that no one could guarantee would resume.

The developments in Kwara coincided with even darker scenes in Niger State. There, armed men overran a school and marched more than three hundred students into the forest. The attack triggered one of the largest abduction responses in recent years. Rather than focus on securing schools and rescuing the victims, the state government opted for a drastic measure. It closed all schools until 2026. The Federal Government went further by shutting at least forty-one unity colleges across the country. Parents who had trusted that federal schools were the safest public institutions discovered that even these spaces were vulnerable.

Advertisement

Behind the headlines lies a complex network of violent actors. Groups linked to al-Qaeda, such as JNIM, and factions of the Islamic State West Africa Province have expanded their reach within parts of the north. Bandit gangs operate across the North-West and Middle Belt with growing confidence. Their operations are driven by two motives. One is the pursuit of money through ransom. The other is the desire to weaken state authority by attacking communities and transport routes. Schools have become attractive targets. A single successful raid delivers a stream of ransom payments.

Statistics from mid-2024 to mid-2025 paint a grim picture. At least four thousand seven hundred and twenty-two (4,722) people were kidnapped nationwide in that period, according to Vanguard newspapers. Billions of naira were paid to secure their release. Many victims were schoolchildren. Many ransom payments went to networks that are openly classified as terrorist organisations. The Kuriga abduction stands as a stark example. Gunmen walked children past multiple checkpoints without interruption. The silence of those checkpoints told its own story. It told armed groups that they had little to fear.

Each government-ordered school closure reinforces this logic. When a handful of criminals can force entire states to lock up classrooms, children learn a painful lesson. They learn that the presence of danger is more powerful than the presence of the state. Communities learn it too. Authorities often promise to reopen schools after conducting security assessments, but many schools never resume normal operations. Some remain permanently shut. Others reopen for a period and then close again after new threats emerge.

Advertisement

The consequences for children are severe. The COVID period taught Nigeria a harsh lesson. Long closures can erase years of progress. Half of school-age children had no learning at all during the pandemic. When schools reopened, many did not return, especially those from poorer households or informal learning centres. Insecurity has now deepened the setback. Tens of thousands of schools across the northern region have been shut or heavily restricted. Children are being pushed out of classrooms into early marriage, petty trading, farming or domestic labour. For some families, this is a matter of survival. For others, it is shaped by fear that school is no longer a safe place.

The education crisis now intersects with a worsening hunger emergency. Across Nigeria, farmers are abandoning fields because of constant threats. Communities in the Middle Belt and North-West speak of farmlands turning into war zones. Bandit attacks and climate pressures have devastated local production. The U N World Food Programme warns that thirty-five million people could face food shortages by 2026 if support collapses after December 2025. In homes where parents struggle to put one meal on the table, school fees and transport fare become luxuries. Children leave school to work in markets, farms, construction sites or distant cities.

A dangerous loop is forming. Violence reduces food production, hunger fuels desperation, and desperate youths become easy recruits for criminal and extremist groups. Education, which should be a shield against this cycle, is losing its strength. When a school closes, a community loses one of its strongest pillars of stability. When several schools close, entire regions slide into uncertainty.

Nigeria once battled classroom shortages that were driven by poverty and weak infrastructure. Today, the challenge is more existential. Schools are being emptied not because children do not want to learn but because a climate of fear has taken hold. If this trend continues, a generation of Nigerian children will grow up bearing the scars of both limited education and persistent insecurity.

Advertisement

Turning this tide demands more than routine statements from officials. It requires a coordinated rebuilding of trust between communities and the state. It requires security operations that prevent attacks, not only respond to them. It requires transparent use of funds earmarked for protecting schools. It requires community-based mechanisms that alert authorities before threats escalate.

The crisis did not emerge overnight. It grew from years of underfunded security, inconsistent governance and the rise of violent actors who study weaknesses and exploit them. Nigeria now finds itself at a crossroads. The choice is between confronting the insecurity that interrupts education or accepting a future where mass school closures become a normal feature of national life.

A nation that cannot keep its children safe in school risks losing more than academic progress. It risks losing its sense of continuity. It risks losing the future that those children would have built. The cost of inaction will be far higher than any ransom ever demanded. To harken is better than sacrifice.

Tosin Adeoti writes on society, governance, and business, weaving history and observation into stories about how people and nations evolve. He is interested in ideas that help us build fairer and more thoughtful communities. He can be contacted via [email protected].

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.