Donald Trump

BY FOLORUNSO FATAI ADISA

Last month, a mutilated body was found decomposing on the tranquil banks of Loch Lomond, Glasgow. A few weeks later, dismembered body parts were discovered in the community around my workplace in Glasgow. And only three weeks ago, I woke to flashing blue lights and police tape sealing off my street, a 52-year-old man had been stabbed to death right at the doorstep of the next house to mine. These are not scenes from a crime drama. They are pieces of Scotland’s recent reality. The cases of violent crime here, though rare by global standards, are quietly on the rise. According to Scottish Government crime statistics (2024), recorded homicides rose to 57 cases, up from 52 the previous year, while knife-related offences remain a persistent concern across Glasgow and Edinburgh.

However, in every tragedy, something profoundly human happens: people rally together. They condemn the act, not the people. They do not claim persecution. They do not weaponise grief. They come forward with information, assist the police, and help the community heal.

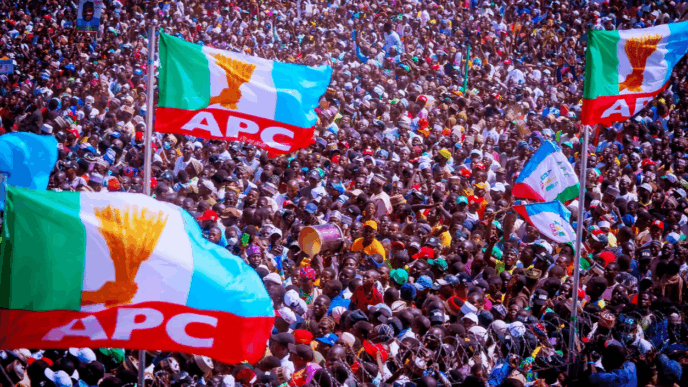

Now contrast that with home, Nigeria. There, tragedy too often becomes a tool of division. Some so-called fundamentalists preach that their religion is holier than others, branding dissenters as infidels. Some ethnic propagandists have vowed to burn the country down simply because they lost an election. The nation’s pain is politicised; its insecurity, misbranded.

Advertisement

Yes, insurgency exists. Yes, people across faiths and ethnicities have been killed in Kaduna, Zamfara, Plateau, Imo, and Borno. But to reduce that complex web of violence to “Christian genocide,” as the U.S. President Donald Trump recently claimed, is both reckless and ignorant. It erases Muslim victims of banditry, kidnapping, and terrorism, and those nameless farmers, imams, and children in the North who have also perished under the same violence.

Words matter. The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED, 2024) shows that over 60% of violent deaths in Nigeria’s north were from communal, criminal, or insurgent attacks not targeted by religion but by geography and vulnerability. Misnaming such tragedies as “Christian genocide” only deepens suspicion and fuels fresh hate.

What Nigeria truly needs now is not another imported narrative but a collective homegrown resolve where citizens join hands with security agencies, communities sharing intelligence, and leaders confronting the monsters of banditry, kidnapping, and terrorism that stalk every region.

Advertisement

And as for America lecturing others on peace, one must only glance at its own mirror. The Gun Violence Archive (2025) has already recorded over 35,000 deaths this year alone from gun-related incidents. That is more than Nigeria’s total death toll from terrorism and banditry combined in 2024 (Global Terrorism Index, 2025). Add to that the U.S. interventions in Libya, Gaza, and Ukraine, and you see a lantern that cannot see its own darkness, preaching light while standing in shadow.

Violence benefits nobody. And those who peddle division in the name of religion or politics must remember: the fire they ignite might one day consume them too.

Folorunso Fatai Adisa is a communication strategist. He holds a master’s degree in media and communication from the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, and writes from the United Kingdom. He can be contacted via [email protected]

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.