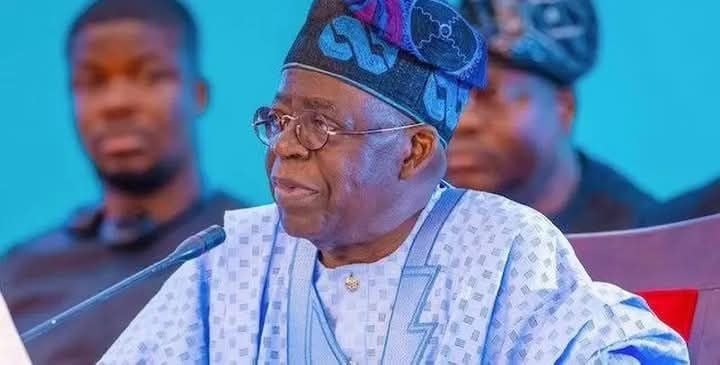

President Bola Tinubu is now halfway into his 4-year tenure. As anyone would expect, opinion is divided over his midterm performance, especially from those who want the conversation to be a choice between good and bad.

In his first two years, the president has implemented key policy reforms, including the removal of fuel subsidies and liberalisation of the foreign exchange regime. These two key policy changes, while they have strengthened the government’s fiscal position and improved the business and investment climate, are yet to translate into tangible welfare benefits. In interrogating the policies, the question is whether or not the government had a choice and, if not, whether the prescriptions could have been delivered in a manner that is painless?

Before President Tinubu was elected in 2023, Nigeria was spending more than 90 per cent of its revenue on debt servicing and borrowing to pay fuel subsidies, which sometimes eclipsed annual total government revenue. The hard pegged foreign exchange regime was as much destructive; it created multiple exchange rate windows which left room for arbitrage and created a situation where the country was depleting its foreign reserves to defend the naira.

The situation created fiscal and monetary distortions, where earnings and borrowings that could be applied to key growth sectors were instead used to fund ruinous subsidies. Foreign direct and portfolio investments, which are some of the barometers for gauging the strength of any economy, plummeted; there was zero confidence in the economy. To put it mildly, Nigeria was in a bad fiscal position.

Advertisement

Build-up to the 2023 election, almost every serious presidential candidate agreed that the subsidies had to go. It did not matter whether you were a party on the right or the left; there was no other way. The consensus at the time was that it was not possible to run an economy in that manner. The country was sliding further down a dangerous hole, and it was only a matter of time before the economy imploded.

For finding the courage to go through with the two signature reforms, the president earned himself the title of a bold and decisive reformer who can damn political consequences for the greater good. The conditions were also right for this purpose because the timing of the subsidy removal also coincided with the take-off of the Dangote refinery. As a result, the once bleak economic outlook is shaping up positively again. In 2024, the country recorded a 3.4 per cent economic growth, the highest in about a decade. Credit rating agency Moody’s has upgraded Nigeria to stable; foreign reserves have increased from $4 billion to $23 billion. The stock market has also sustained its bullish run, attracting more portfolio investors and delivering real-time returns to investors.

On the downside, the policies, although not intended, also led to higher food inflation and energy bills, which have both contributed to a monumental cost-of-living crisis. However, when applying these sorts of prescriptions, the fallouts are not mutually exclusive – a situation that is described as the reform and pain nexus. Therefore, while the fallouts are indeed painful, they do not essentially invalidate the necessity of the reforms.

Advertisement

The question then is whether or not the reform could have been delivered in a painless manner. While it is hard to say with certainty, in hindsight it is easy to argue that shock therapy, which was an attempt to implement as many reforms as quickly as possible, may have in part contributed to the cost-of-living crisis. There is a valid argument that perhaps if the reforms were sequenced in a way that provided people with time to make necessary adjustments and build resilience, it may have made their experience better.

However, there is also the legitimate argument that if the president had not frontloaded the reforms or attempted to dally, he may lose the political will or even face resistance from entrenched interests that may stand in the way of progress. This is perhaps the reason I always argue that public policy is quite precarious. There are never easy choices; for every decision there are potential benefits and costs, and what it demands, therefore, is that political leaders must always have the courage to be decisive.

Going into the second half of the president’s administration. One of the major expectations from many Nigerians is how the economic growth translates into tangible welfare benefits and more money in their pockets. There is also the argument that the president cannot afford another consequential reform at this time, with just two years into an election; such a decision would not only be a political miscalculation, but it could also worsen the current situation. People need time to adjust to the shock of the existing reforms.

The president must also, among other things, go further and faster to bring down inflation to acceptable levels; headline inflation at 24 percent is far too high. The government must also work to be more fiscally prudent and commit to eliminating waste; instead, government should accelerate investment in key sectors that can support the economy, especially agriculture and manufacturing.

Advertisement

The economy is without any doubt on the rebound, but beyond the fundamentals, government must work to ensure that the growth translates into more money in people’s pockets and tangible welfare benefits.

Awogbenle, a development and public policy professional, writes from United Kingdom. He can be reached via [email protected].

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.