President Bola Tinubu walks into the green chamber on Democracy Day

BY JOSHUA OLUFEMI

Last week, I wrote something about memory. About how civil society — the old guard, the foot soldiers, the ones who gave sweat and scars to make Nigeria breathe freely — should not be forgotten, even as we innovate, build, disrupt, and move forward.

Then June 12 happened.

And I saw the honours list.

Advertisement

And I paused.

Because on that list were names, not just of people I respect, but people I know. People I’ve worked with. People I’ve watched shape the air we now breathe in civil society and media. People like Ayo Obe, Kunle Ajibade, Bayo Onanuga, and my former boss and mentor, Dapo Olorunyomi — “Dapsy”, as we call him.

For me, seeing his name there was more than just excitement. It was a memory. It was justice, even if long overdue. It felt like a quiet nod from the country, finally saying, “we see you.”

Advertisement

But I didn’t stop at the celebration. I kept thinking about something deeper: the fact that recognition itself is a mirror. What we choose to reflect on reveals a great deal about our values and the people we hold in esteem in Nigeria. While this list does highlight some successes, it’s important to note that many of those who received national honours were journalists and civic activists—individuals who bravely opposed military regimes at a time when remaining silent would have been the safer option.. People who used pain and pen to fight power. And those who still do.

It almost felt like a NADECO–media–civil society roll call. And for once, that wasn’t a bad thing. That generation deserves their flowers. They’ve fought battles some of us have only read about.

But that’s also the thing: so much of their story is missing from the record.

When I asked one of my colleagues to pull together a quick profile on Dapo Olorunyomi, most of what they could find online dated back just a few years before 1999. Almost nothing from the decades before. And that’s a problem.

Advertisement

We talk a lot about the future, and we should. But if we don’t preserve the past, we lose the very maps that show us how people got through the storms before us.

There should be fireside recordings, interviews, books, and documentaries. Not just for the big names, but for the many unsung builders of Nigeria’s media, civil society, and democracy. Not just to clap for them, but so we can learn. So we can connect the dots. So the next generation isn’t left wondering how the story even began.

Because let’s face it, a lot of Gen Zs were still toddlers in 1999 when civilian rule returned. Some were not even born. But I hope this award list made a few of them pause. Google a few names. Ask a few questions. Maybe even read a book or two.

But beyond pausing, I hope they reflect.

Advertisement

Consider that the freedom to post, organise, and speak out is a hard-won privilege. This struggle took place not only online but also in courtrooms, newsrooms, detention centres, and in exile.

And while they’ve brought energy, creativity, and reach to the space, I hope they also learn that change is more than hashtags and camera moments. It’s policy. It’s structure. It’s strategy. It’s cohesion. It’s staying power.

Advertisement

Because the work ahead is no less urgent than the work behind.

Still, as I looked at that list, something kept bothering me.

Advertisement

Why is it that only a few sectors seem to be recognised over and over again? Why are media and politics the only places we seem to honour people for service?

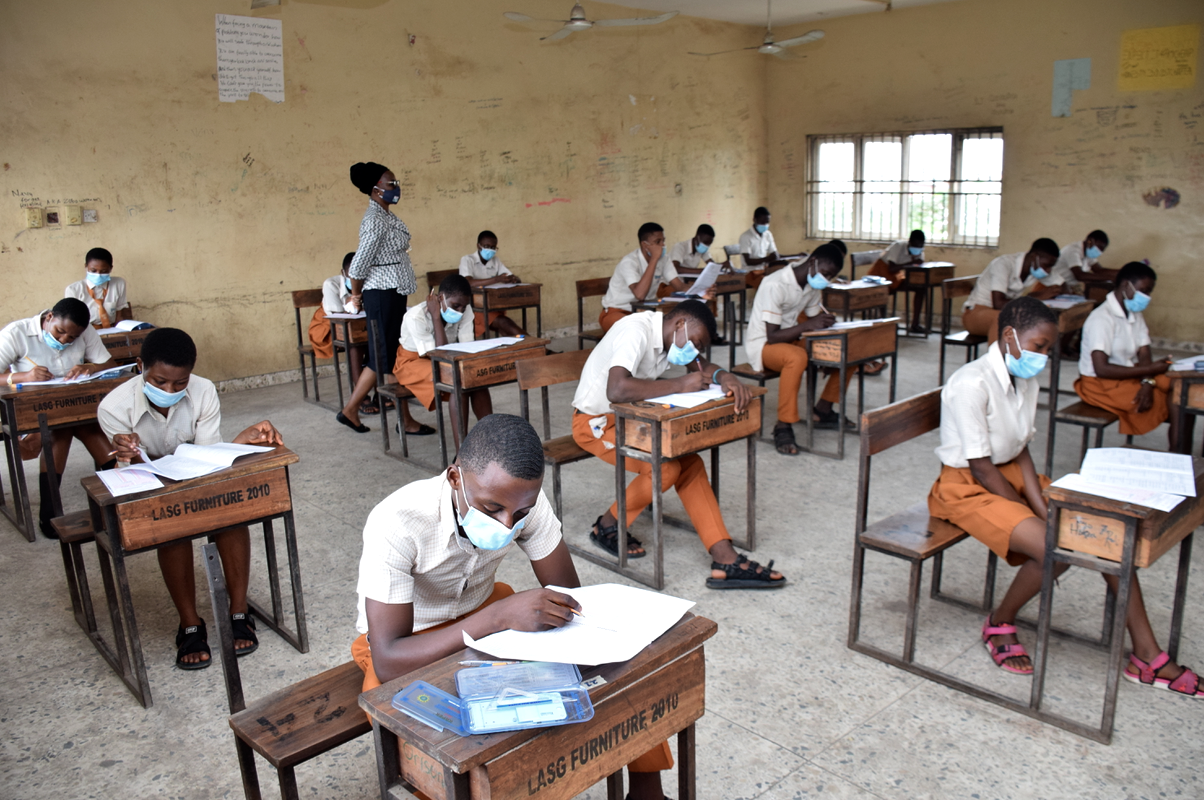

Where are the teachers who’ve taught for 30, 40 years, raising leaders quietly in classrooms across the country?

Advertisement

Where are the doctors and nurses who serve in broken systems, yet still show up every day?

Where are the librarians, archivists, midwives, and public school principals? Where are the security officers, not just the high-ranking ones, but those who risk their lives in quiet, effective service?

Where are the informal sector champions? The traders in Kantin Kwari, the farmers in Benue, the women in Bodija Market who’ve kept families and economies afloat for decades? Some of these people have trained hundreds, created jobs, and supported communities in ways that policymakers only dream of.

We say we want more patriotism, more service, more excellence, but do we celebrate it where it exists?

I must say I had expected this administration to widen the net. I thought we’d see names from tech, business, health, and education who’ve used innovation to power national progress. We’ve seen such recognitions in the past, and we need more of them now.

Recognition should not be about friendships, favours, or proximity to power. It should be about impact, consistency, and sacrifice. About service across all walks of life.

Because if we only decorate people we know, we erase the everyday heroes we should know.

So yes, I commend this list. But I also critique it. Because it must become broader. Deeper. Fairer.

And that brings me back to us.

We, too, must do better at documenting and dreaming.

We must preserve the voices that built the roads we walk on now. That means writing, recording, sitting down with elders, mentors, and forgotten names. It means putting them in books, podcasts, short films, and public archives.

And we must also dare to ask: what are we building for 2050?

If our elders fought to reclaim democracy 30 or 40 years ago, what is the dream we’re ready to fight for today? What kind of Nigeria do we want our children to inherit and what are we willing to do to get there?

You can’t love a country you’re not committed to.

You can’t inherit a legacy you don’t understand.

And you can’t build a future you’re too distracted to imagine.

So yes, Tinubu remembers.

And I’m glad.

But this work of remembering: of honouring, of learning, of building, belongs to all of us now.

Let’s not waste it.

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.