BY LEKAN OLAYIWOLA

The deeper problem of Nigeria’s education crisis is not simply “too little money,” but a funding architecture that fails to match regional realities, including conflict, displacement, floods, urban crowding, language gaps, and a system that rewards spending inputs over learning outcomes.

The education sector needs funding that targets areas of need, adapts to changing conditions, and delivers results that households can see and feel.

Nigeria’s education crisis, deep and uneven

Advertisement

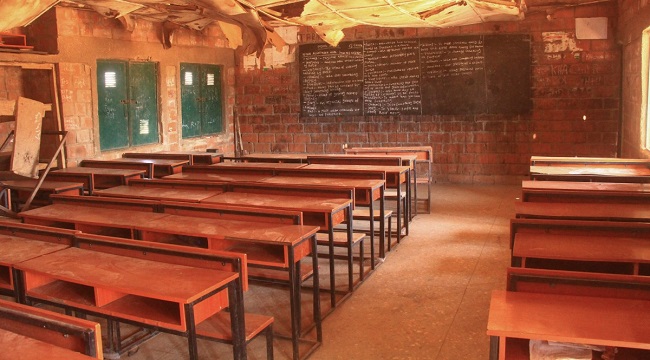

World Bank data shows that 72.6% of children aged 7–14 cannot read with full comprehension, while 17.1 million children remain out of school. With pupil-to-classroom ratios nearing 64:1 and public spending at just 10% of the national budget (roughly $23 per capita, far below global benchmarks), the system is underfunded and overstretched.

But national averages obscure sharper regional disparities: the North West and North East suffer concentrated learning deprivation, coastal states face flood-induced disruptions, and urban centres grapple with overcrowding and rising costs.

A uniform federal budget cannot address this fragmented reality; what’s needed is a conflict-sensitive, regionally adaptive approach that reflects the true geography of harm.

Advertisement

Why Bigger Budgets Aren’t Moving the Needle

Spend follows payroll, not pedagogy. Most federal and state education budgets are absorbed by salaries and recurrent costs—necessary, but insufficient. Classrooms stay congested, toilets are broken, labs are unfunded, and connectivity is absent.

Funds stall on the way to the classroom. States routinely fail to provide counterpart funding to access available Federal grants. Since 2023, over ₦45.7 billion in UBEC grants earmarked for classrooms have remained stuck in fiscal purgatory.

Insecurity has shuttered thousands of schools across the North West over the past few years; insurgency and displacement continue to disrupt learning in the North East; major floods in 2022 swamped schools across the South South (Bayelsa alone shut 18 schools for months); and volatile urbanisation drives class sizes up and attendance down. Yet budget lines and formulas barely flex when crises hit.

Advertisement

Regional Realities and Adaptive Budgeting

In the North West, banditry and abductions have hollowed out schools. The binding constraint is safety. Budgets should fund community vigilance compacts, trauma counselling, secure perimeters, flexible farming-season timetables, and contingency disbursements that activate immediately after attacks.

Nigeria’s ₦144.8 billion Safe Schools Plan (2023–2026) is a legal anchor, but states must localise it into real protection and attendance recovery.

The north-east’s protracted displacement requires accelerated learning to compress lost years, Hausa/mother-tongue bridging, and stipends that keep girls in class. Hardship allowances, secure housing, and rotational deployment are essential to retain teachers. Federal transfers should be weighted for displacement and verified catch-up, not just budget lines.

Advertisement

In the north-central, farmer–herder violence demands mobility: conflict-season calendars, mobile classrooms, and mediation cells linking school heads with local peace actors. Attendance continuity plans, transport vouchers, safe temporary sites, and remedial modules must be pre-funded.

The south-south’s 2022 floods proved that schooling can vanish overnight. Budgets should include flood-risk triggers releasing funds for raised classrooms, canoe/bus routes, and 30-day catch-up cycles.

Advertisement

In the south-east, economic fragility pulls children out of class. Solutions lie in micro-credit for caregivers, evening schools, and police–community pacts to secure routes.

In the south-west, overcrowding demands double shifts, para-teacher coaching, and real TVET–employer pipelines. Price constraints, meals and transport are the fastest levers to stabilise attendance.

Advertisement

A Federal Formula That Pays For Results, Assuages Grievance

How do you shift billions without starting a regional food fight? A transparent, rules-based weights and public dashboards.

Advertisement

Need Weights: Out-of-school rates, learning deprivation, insecurity incidents, flood risk, and pupil-classroom ratios drawn from NEMIS, state EMIS, and independent audits, determine each state’s “need score.” The World Bank’s zone-level deprivation map is a ready starting scaffold.

Equity Floor: Every state gets a guaranteed base to avoid “winner-take-all” optics. Above the floor, funds scale by need weights.

Performance Ladder: States unlock the next tranche only after hitting simple, verifiable markers—attendance rebound after closures, classrooms added and staffed, girls’ re-enrolment rates, and foundational literacy gains measured with short, publicly proctored tests.

Crisis Snap-On: The Safe Schools plan becomes a budget “window” that disburses automatically when triggers are met, attacks are reported and verified, the flood gauge threshold is crossed, and displacement is declared.

Grievance Guardrails: A do-no-harm review (with community reps, women’s groups, and faith leaders) screens every allocation shift for unintended consequences, creating perverse incentives to exaggerate insecurity or neglect minorities.

Not How Much, But How Money Moves

With the design set, unblock the bottlenecks that keep funds from classrooms.

Reform UBEC matching rules so that states that can’t post the full cash match can still access a minimum grant by meeting governance conditions (procurement transparency, school-based management committees, open data).

Convert the remaining match into in-kind milestones, e.g., verified teacher postings to rural schools. Given ₦45.7 billion recently sat idle for years, unlocking even half would be transformational.

Tie cash to children, not ledgers. Fund contact time and learning checks rather than line-item inputs. If a school can verify 180 days of instruction and measured reading gains for JSS1, it gets the tranche regardless of whether the ceiling was painted in Q2 or Q4.

Publish a national “Learning and Safety” dashboard. Put attendance, closures, teacher vacancies, and short literacy/numeracy checks online, school by school. Let parents see what the money bought. The point isn’t to shame; it’s to steer.

The Politics of Plausibility

This is not a blank cheque appeal. It is a reprogramming of existing flows to track Nigeria’s real risk map. The Safe Schools financing plan already exists; use it as the crisis window. The World Bank’s deprivation profile identifies where learning losses are deepest; use it to weight transfers.

UN benchmarks and UNICEF finance guidance establish why Nigeria’s envelope must rise over time; use them to justify a medium-term glide path toward the 15–20% share, but only if each extra naira buys measurable gains.

Above all, resist the easy false choice between “more money” and “better governance.” Nigeria needs both, but the sequencing matters: fix the pipes while you fill the tank.

These are not partisan ideas. They are conflict-sensitive management tools that help every governor show parents something concrete within months: safer schools, shorter classes, and children reading again.

From Budgets as Headlines to Budgets as Lifelines

Money must track where children are missing, where violence or floods close gates, where classrooms suffocate. The past five years proved that “more” is not enough.

The next five must prove that smarter, faster, fairer spending keeps children in school, keeps them safe, and helps them learn. Until then, rising line items will keep buying falling futures, and families will know the government failed the test.

Lekan Olayiwola is a peace & conflict researcher/policy analyst. He can be reached via [email protected]

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.