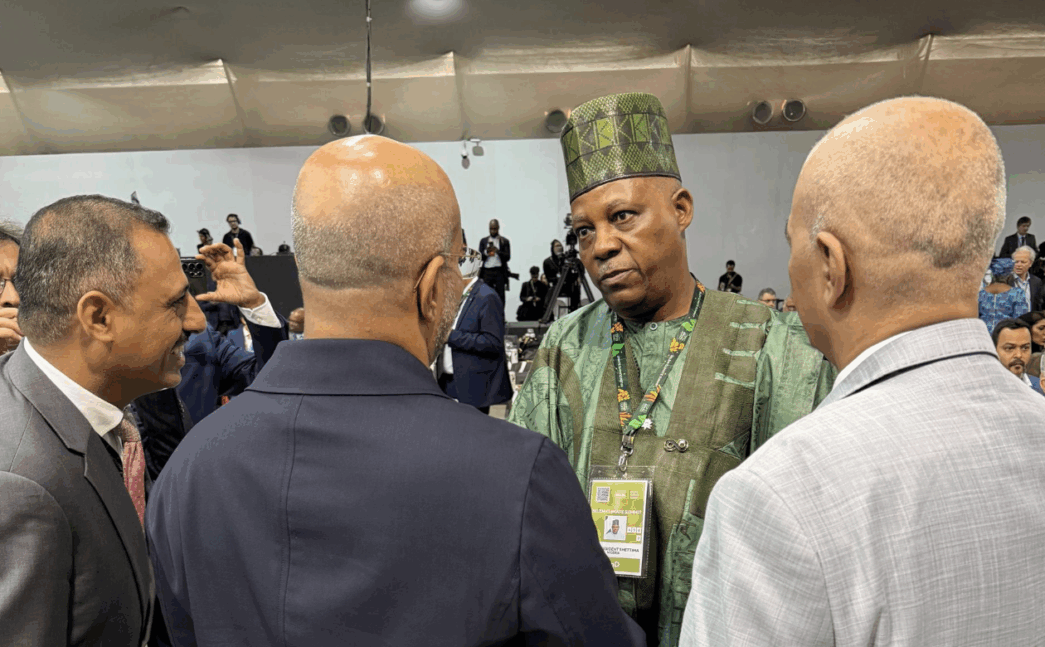

VP Kashim Shettima (M) interacts with world leaders at the opening of the Leaders’ Climate Summit (COP30) in Belém, Brazil

BY IBRAHIM ABDULLAHI SHELLENG

Nigeria’s climate ambitions have consistently outpaced its financial capacity to deliver them. While policy frameworks multiply and international commitments grow, the question of how to pay for climate action remains stubbornly unanswered. Communities facing immediate climate threats cannot wait for solutions funded by distant promises. The recent operationalisation of the Climate Change Fund by His Excellency, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, at the meeting of the National Council on Climate Change, bridges this wide gap, creating the financial architecture needed to transform climate policy into tangible interventions.

The country is at odds with several interconnected obstacles in mobilising climate finance at scale. Robust pipelines of bankable projects capable of drawing down available international funding remain scarce. Meanwhile, accessing major climate funds like the Green Climate Fund can take two to three years, far too long when adaptation projects require immediate action. Livelihoods are vanishing due to flooding, drought, and erosion; these communities require funding approval now, not years from now. Adding to these timing constraints, climate finance arrives through multiple channels: different ministries, various projects, multiple donors, with no central coordination or visibility.

The Climate Change Fund, enshrined in the Climate Change Act of 2021, was designed specifically to address these challenges. Operationalising the fund required developing detailed structures for governance, resource mobilisation, management, and disbursement that would meet international standards while serving Nigeria’s peculiar needs. Alongside development partners, Nigeria developed an operational framework acknowledging the reality that traditional public fund management approaches would struggle to mobilise resources at the necessary scale. Something different was needed: in entirety, a structure capable of attracting diverse investors with varying risk appetites and return expectations. There is a work in progress of a three-window architecture, each serving distinct purposes and investor profiles that would allow various investors to participate based on their objectives and risk tolerance. The elegance of this multi-window structure is in how it addresses barriers that previously prevented private sector participation. With these distinct windows, defined objectives, and return profiles, the fund addresses private sector concerns while maintaining its development mission.

Advertisement

Notably, this is not exclusively about international capital. Domestic investors such as domestic banks and subnational entities can also participate. As climate impacts intensify, Nigerian businesses increasingly recognise that climate action is not the government’s responsibility alone. It is a business necessity. Nigeria could lose 30 percent of GDP by 2050 due to climate impacts, according to the World Bank.

Initial projections suggest the fund could mobilise around $2bn in its early years, though this baseline depends on global geopolitical dynamics and funding flows. Demonstrating effective deployment of resources matters most. Complementing this architectural design, the governance framework reinforces investor confidence. Rather than opaque public management, professional fund management will ensure transparent operations under a strong governance board, ensuring accountability in resource utilisation.

Moreover, because transparency is key and serves dual purposes: both as an accountability measure and a strategic tool for mobilising additional finance, the Honourable Minister of Finance and Coordinating Minister of the Economy, Wale Edun, has committed to establishing a climate finance tracking dashboard that will monitor all climate funding flowing into the country. This system will provide visibility into what resources Nigeria receives, how they are allocated, which projects get funded, and what measurable outcomes they produce.

Advertisement

Rightly, for citizens, this creates see-through accountability. Nigerians can track whether climate finance reaches communities bearing climate impacts or gets lost in bureaucratic processes. For international partners, it demonstrates a commitment to responsible resource management, making additional investment more attractive. This transparency also extends to project selection and fund allocation. The fund’s operations will be guided by Nigeria’s climate policy framework: Nationally Determined Contribution (NDCs), National Adaptation Plan (NAP), Energy Transition Plan (ETP), and National Development Plan. These documents identify priority sectors for both mitigation and adaptation, ensuring funding aligns with the national climate strategy.

Operating in concert with these priorities, the Climate Change Fund works synergistically with the National Carbon Market Activation Framework (NCMAF), also approved at the NCCC meeting. The carbon market framework provides regulatory clarity for how carbon projects will function in Nigeria, including institutional arrangements, pricing mechanisms, and verification standards. The fund can provide first-loss guarantees for carbon projects, reducing risk for private investors. It can offer funding to help promising carbon projects reach commercial scale. Significantly, proceeds from carbon credit sales flow back into the fund, creating a reinforcing cycle where successful carbon projects generate resources to fund additional climate action. This interconnection allows Nigeria to leverage its carbon market potential to generate resources for broader climate interventions. Revenue from forestry carbon projects can fund drought adaptation programmes. Income from clean cooking initiatives can support coastal protection infrastructure.

Priority sectors for the fund’s initial interventions are drawn directly from national climate plans. The Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) pinpoint energy, transport, industry, agriculture, and waste for emissions reduction, while the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) urgently addresses agriculture, water resources, forestry, biodiversity, health, and coastal zones. The fund’s structure allows for flexibility. Climate challenges do not respect sectoral boundaries, and a single intervention might address water security, agricultural productivity, health outcomes, and environmental quality simultaneously.

Understanding precisely how climate change affects different regions, populations, and economic sectors is essential for designing effective interventions. The fund can contract consultants and civil society organisations to conduct comprehensive climate impact assessments, building the knowledge base for evidence-based climate action. While the fund’s structure operates at the national level, its ultimate impact is on the ground. This requires top-down resource flows and bottom-up capacity building. Communities need to understand what climate finance can provide, how to access it, and how to protect climate investments once made.

Advertisement

Subnational governments — state and local authorities — will be essential partners. They are closest to affected communities, best positioned to identify local priorities, and necessary for coordinating across sectors at the regional level. The fund’s structure allows these entities to access resources directly, bypassing bureaucratic delays that have historically slowed climate action.

The operationalisation of the Climate Change Fund is more than improved climate finance access, as it is a monumental shift in how Nigeria approaches development financing. Climate finance is not auxiliary funding for environmental projects because it is increasingly central to how we finance infrastructure, support agriculture, develop energy systems, build resilient communities, and drive economic diversification. The current administration has emphasised economic diversification beyond oil dependence. Climate finance, whether through the Climate Change Fund, carbon markets, or green bonds, provides alternative financing streams for development priorities that simultaneously build national resilience and reduce emissions.

Looking toward international engagement, the fund validates Nigeria’s commitment to climate action. The country is building institutional infrastructure to deploy resources effectively while establishing transparency mechanisms and creating governance structures that meet international standards. Strategically, the goal was to get the fund approved ahead of COP30 in Belém because it serves as the ideal launchpad for comprehensive national climate work. Through this, Nigeria can showcase progress and intentionality, a cue to investors of the country’s seriousness regarding climate action and the high-level government commitment necessary for successful partnerships.

The heavy lifting is excitingly unavoidable. From the core task of establishing professional fund management structures to the vital work of developing subnational capacity and tracking measurable outcomes, every component of this mission will require sustained and dedicated effort. The institutional foundation exists to do this work systematically. Nigeria has legal authority, operational structures, political commitment, and international partnership. The Climate Change Fund won’t solve every challenge Nigeria faces from climate change. But it provides essential infrastructure for mobilising the resources needed to confront those challenges at scale. That’s what the fund means for climate finance in Nigeria.

Advertisement

Ibrahim Abdullahi Shelleng is the senior special assistant to the president on climate finance and stakeholder engagement, seconded to the National Council on Climate Change. He drives Nigeria’s mobilisation of climate finance and stakeholder partnerships to advance the nation’s green transition.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.