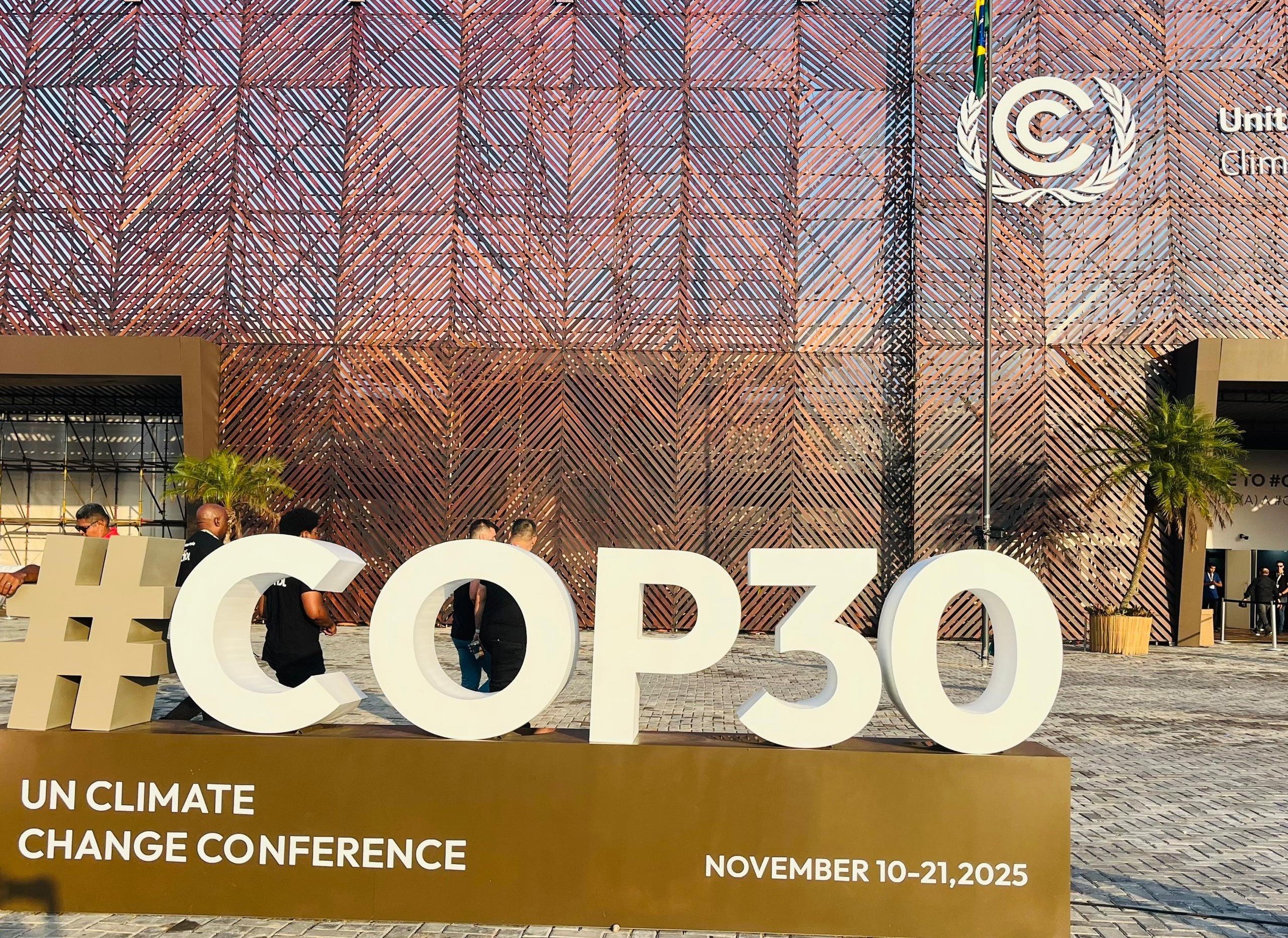

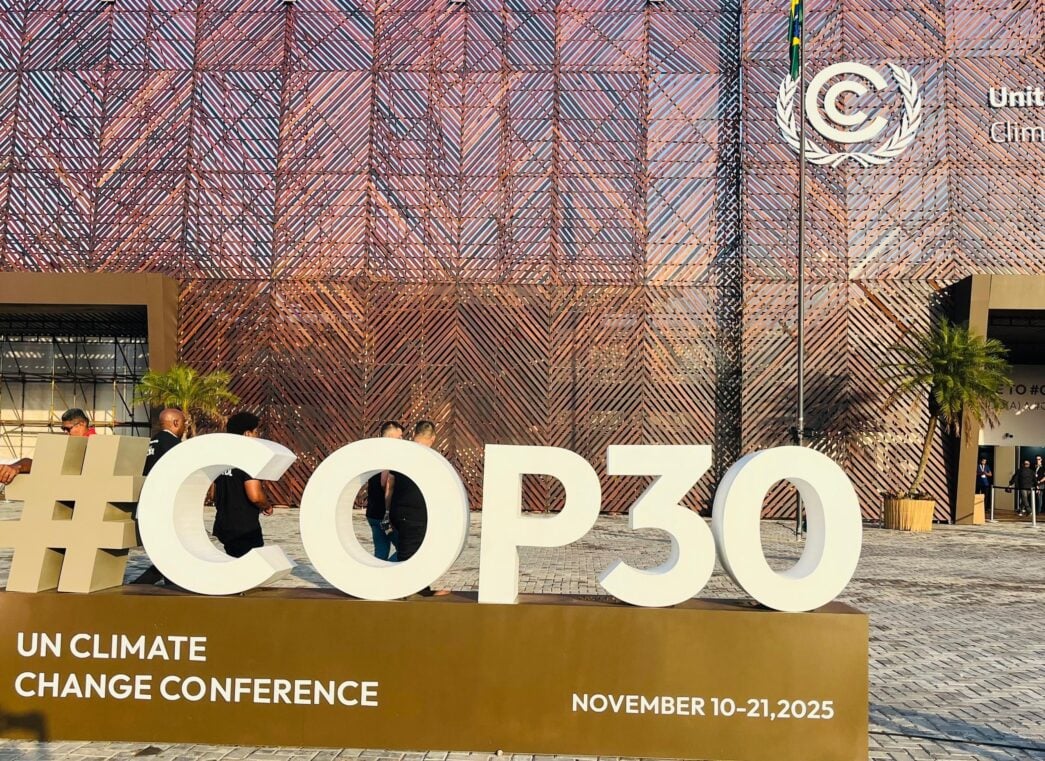

COP30 closed on Saturday after overnight negotiations pushed the summit deep into overtime, with countries settling for fragile compromises on adaptation finance and fossil-fuel language.

By evening, the COP30 president struck the gavel, confirming consensus on the “mutirão” cover text — the summit’s final outcome — two weeks after talks opened in Belém on November 10.

Throughout the talks, the African Group of Negotiators (AGN) insisted that adaptation finance for developing nations must be tripled from the $40 billion pledged at COP26 in Glasgow, warning that anything less ignores the scale of climate disasters already battering the continent.

Advertisement

Negotiators also sought to streamline a global set of indicators for measuring adaptation resilience, but campaigners argued they would be “meaningless” without the finance required to implement plans.

A recent United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report estimates that developing nations will need between $310 billion and $365 billion annually by 2035 to cope with worsening climate impacts, far beyond what a $120 billion tripling pledge would deliver.

Speaking during the closing plenary, Diana Mejia, AILAC chair from Colombia, said COP30 was meant to be an “adaptation COP”, yet the final outcome “falls short of reflecting the magnitude of the challenges facing the most vulnerable on the ground”.

Advertisement

She said the global goal on adaptation must be accompanied by finance, or it risks becoming an aspiration, not an outcome.

Mohamed Adow, director of Power Shift Africa, said the promise to triple adaptation finance lacks clarity on a base year and has now been pushed to 2035, leaving frontline nations without the support they urgently need.

Adow said the outcome “does nothing to narrow the adaptation finance gap” and reflects a “deeply worrying” lack of urgency.

Ali Mohamed, Kenya’s special climate envoy, said developed nations must honour their adaptation commitments and acknowledge Africa’s central role in the global clean-energy transition.

Advertisement

“Kenya, and Africa, stand ready to lead, but resilience and adaptation cannot remain afterthoughts for a continent responsible for less than four per cent of global emissions,” he said.

NO PATHWAY TO PHASE OUT FOSSILS

Another major fault line at COP30 was how countries should progress the historic COP28 agreement to “transition away from fossil fuels”.

The EU pushed for a credible roadmap to reduce global reliance on oil, gas, and coal, rejecting an earlier draft for lacking concrete mitigation pathways and warning that without stronger fossil fuel language, there would be “no deal.”

Advertisement

But oil-producing countries — including Arab states and several developing nations — resisted, arguing that fossil fuels remain central to their economies and that they must be given space for development just as wealthier nations once were.

The final text was adopted without a fossil fuel mitigation roadmap, drawing objections from countries like Colombia, which said the mitigation work programme still lacks direction on how the transition should unfold.

Advertisement

Linda Kalcher, executive director of Strategic Perspectives, said the EU and allies in Latin America “defended their core interest in accelerating the energy transition despite strong opposition from major fossil producers”.

Jennifer Morgan, former German climate envoy, added that despite pushback, “multilateralism is still working” to advance global climate ambition.

Advertisement

PROGRESS ON JUST TRANSITION MECHANISM

COP30 also established a new just transition action mechanism to ensure workers and frontline communities are not left behind as economies shift to renewables.

Advertisement

Simon Stiell, UN climate change executive secretary, said COP30 showed that “climate cooperation is alive and kicking”, even amid political divisions.

The UN climate chief said while acknowledging frustrations over finance and fossil fuel ambition, the 194 nations had stood firm in solidarity, sending a clear political and market signal that “the global transition to low emissions and climate resilience is irreversible”.

Stiell said the agreement to triple adaptation finance, despite its shortcomings, reflects a recognition that more countries need support as climate disasters escalate.

“I’m not saying we’re winning the climate fight, but we are undeniably still in it, and we are fighting back,” he said.

Leon Sealey-Huggins of War on Want hailed the mechanism as “a vital victory that anchors the fight for justice within the UN”, though concerns remain about how the mechanism will be financed.

Teresa Anderson of ActionAid International called the mechanism a “huge win” for workers, women, and civil society groups demanding protections during the transition.

As delegates made their way out of Belém — the gateway to the Amazon — the city offered a stark reminder of the crisis they came to address.

Days of heavy rain and flash flooding left streets waterlogged, emphasising the urgency of scaling up adaptation finance.

This report was produced with support from Sahara Group and the Kaduna state government