Across northern Nigeria, and especially in Yobe, years of conflict and displacement have left deep gaps in childhood immunisation | Photo credit: SCIDaR

When Hassana Salihu gave birth to her first child in Damaturu, Yobe state capital, the sound of ululation filled the compound. Neighbours arrived to sing, clap, and pray for the newborn’s health. Her grandmother sprinkled perfume across the room while aunties offered advice that carried the weight of tradition.

“Protect the baby from the cold air,” one said. “Don’t let strangers hold him,” another warned. Before long, the conversation turned to the matter of vaccinations. One neighbour leaned in, lowering her voice.

“These injections are not good for small children. I know a woman whose baby fell ill the day after. They say it can even make female children infertile later,” she said.

Others nodded, repeating stories they had heard in markets and at naming ceremonies. A few insisted the clinics charged money even though they claimed the vaccines were free.

Advertisement

Hassana listened quietly. She had seen the posters at the health centre declaring that immunisations were free and lifesaving. But here, in her own courtyard, the chorus of warnings felt louder.

“I didn’t know what to believe,” she later admitted. “Everyone had something different to say, and most of it made me afraid.”

As a first-time mother, she carried her baby everywhere with care, reluctant to take a risk. The clinic was only a short walk away, yet she avoided it for days.

Advertisement

In Yobe, she was not alone. Childhood vaccination has long faced barriers that have little to do with supply. Parents hesitate not because the vaccines are missing but because clarity is absent.

Rumours travel quickly; uncertainty takes root faster than official reassurances. Health workers and town criers try their best, but the pace of misinformation is relentless.

For new mothers like Hassana, doubt often feels safer than action.

A DIGITAL DOORWAY TO RELIABLE INFORMATION

Advertisement

One evening, while scrolling through her phone, Hassana came across a Facebook advert. The image was familiar — a Nigerian social media influencer she recognised. The message was simple: vaccines were free, and parents could get details directly on WhatsApp. Curious, she tapped.

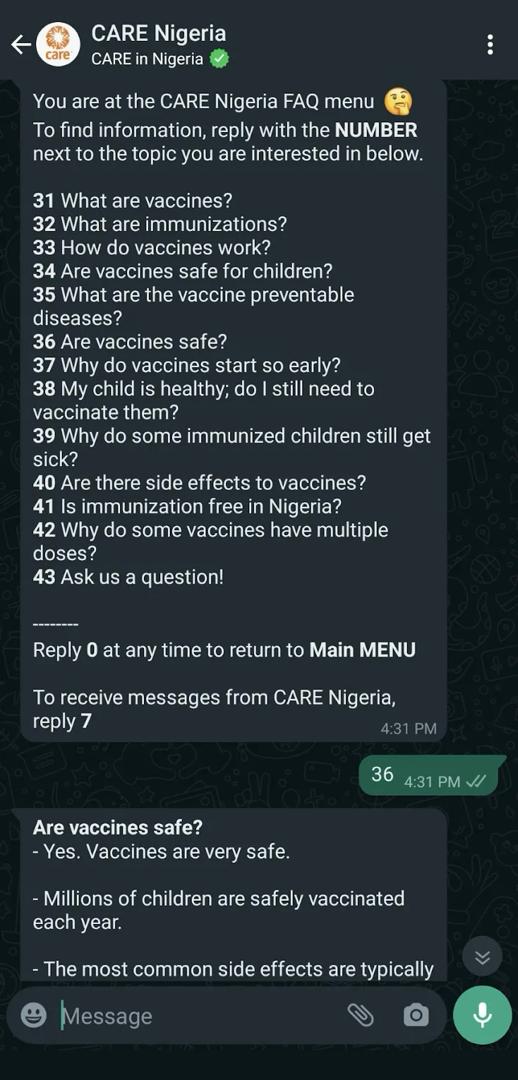

Within seconds, her phone opened a chat window. “Welcome to CARE Nigeria Chatbot. Here, you can learn about CARE Nigeria and vaccinations”, the first message read.

A menu of options followed: where to find the nearest clinic, answers to common questions, details of the immunisation schedule. For Hassana, it was like stepping into a conversation where she could ask what she wanted, without fear of judgement.

This was the chatbot built by CARE Nigeria in 2022, designed to meet parents in the very spaces where they already talked and shared information. Unlike a flyer, which could be misplaced, or a health worker’s visit, which might come only once, the chatbot lived in Hassana’s pocket — available day or night, ready to answer questions in real time.

Advertisement

She picked her ward and LGA, and almost instantly, a list of nearby health centres appeared on her screen. She asked about side effects, and the chatbot explained what to expect after routine immunisations: mild fever, tenderness at the injection site, nothing dangerous.

When Hassana asked whether she needed to complete the entire schedule, it emphasised why each vaccine mattered and how diseases could return if doses were skipped.

Advertisement

Behind this digital exchange lay months of preparation. CARE Nigeria’s team drew on resources from the ministry of health, their own experiences working in Yobe, and daily feedback from health workers. The aim was to build a platform that spoke directly to the doubts circulating in households and markets, not in abstract technical terms but in plain, practical language.

Yet, simply creating the chatbot was not enough. Families like Hassana’s would never stumble across it without help. To bridge that gap, CARE Nigeria, with support from Meta, ran a three-phase Facebook advertising campaign from December 2022 to February 2023.

Advertisement

The adverts used simple, striking messages: vaccines were free, clinics were nearby, and parents could chat directly for answers. Some featured Nigerian influencers. Others showed a vaccine calendar. All were designed to nudge users from curiosity to conversation. Each advert linked straight to the WhatsApp chatbot, turning a glance at the screen into a gateway to trusted information.

The campaign unfolded in stages. The first phase introduced the service, reaching 1.9 million people. The second phase refined the visuals and content, adding the calendar, and reached another 1.7 million. The third phase retargeted those already exposed, this time inviting them to complete a survey embedded in the chatbot. By the campaign’s close, 3.6 million people had seen the adverts. For Hassana, the effect was immediate.

Advertisement

“When I saw that the vaccines were free, I wanted to be sure. I asked the chatbot, and it gave me the location of the clinic. That was when I decided to take my baby,” she said.

WHAT THE NUMBERS REVEAL

Hassana’s decision reflected a broader pattern. Over the course of the campaign, the chatbot recorded 15,000 unique conversations. What stood out was their length. Each conversation averaged about 9.7 messages, 70 per cent longer than a similar project run by CARE in Bangladesh. Nigerian parents were not merely glancing; they were engaging, probing, and returning for clarification.

Nearly 2,700 users — 18 per cent of the total — opted in to receive future immunisation-related updates. While modest, this group represented a steady pool of parents open to continued dialogue.

The survey feature offered deeper insights. Of the 556 people who accessed it, 244 completed it fully, a 43.9 per cent completion rate. Among them, 76.6 per cent said they would recommend the chatbot to friends or family. Sixty-eight per cent rated it four or five stars, and 60 per cent said they now had a clearer understanding of why immunisation mattered.

Geography added another layer to the findings. In Yobe, where CARE Nigeria already ran offline programmes with health workers and community leaders, engagement rates reached nearly 40 per cent — far higher than in other states. The lesson was clear: the chatbot was most effective where it complemented existing efforts rather than standing alone.

For Habeeb Suleiman, CARE Nigeria’s communication and advocacy officer, this broader reach was the most remarkable outcome.

“The chatbot on WhatsApp provided us with a lot more reach than we were ever able to imagine previously,” he said.

“We needed to build the service to be able to reach key stakeholders who influence decision-making within family households. We were able to do that by reaching not only mothers, but also religious and traditional leaders.”

That mattered for women like Hassana. In many households, mothers were not the sole decision-makers. Fathers, grandparents, and community elders played powerful roles.

By leveraging WhatsApp — a platform used for family updates, trade, and religious groups — the chatbot reached circles of influence that traditional campaigns often struggled to penetrate.

WHAT STILL STANDS IN THE WAY

Still, the challenges were significant. The overall conversion rate from adverts to chatbot use was eight per cent, just over half of CARE’s benchmark of 15 per cent, based on peer data. Reaching millions through adverts did not always translate into active use.

Connectivity gaps were also an issue. In rural Yobe, network coverage is patchy, and families without smartphones remained excluded. Even those with access often struggled with English literacy. The chatbot’s initial design was entirely in English, limiting its usefulness for the largely Hausa-speaking, low-literate communities it aimed to serve. Hassana could navigate the messages, but many of her peers could not.

“The specific community we built the chatbot for in Yobe state includes a low-literate population whose primary language is Hausa, not English. By translating the current content to Hausa, we believe we will have a lot more reach, impact, and engagement in the community,” Suleiman said.

Ad performance also revealed something interesting. Messages emphasising that vaccines were free consistently outperformed others. Campaigns focused on calendars or generic appeals drew less engagement. This suggested that misinformation about hidden costs weighed more heavily on parents’ decisions than abstract doubts about vaccine safety. Practical clarity, not just medical reassurance, was key.

CARE Nigeria says it has since moved to act on these lessons. Translation into Hausa is underway, with the expectation of dramatically extending reach among the intended audience.

The organisation says plans are also in progress to broaden the chatbot’s content to include nutrition, food insecurity, and social norms, making it a more comprehensive health companion.

For Hassana, those next steps will come later. What mattered most was the decision she made one morning, after days of hesitation, to walk into the neighbourhood clinic, register her child for immunisation, listen as the nurse explain the schedule, and tuck away the card that listed the next appointment.

For her, the chatbot turned uncertainty to assurance — a shift she now carries into conversations with her family and neighbours.

This story was produced with support from Nigeria Health Watch as part of the Solutions Journalism Africa Initiative.