BY USMAN BABAJI

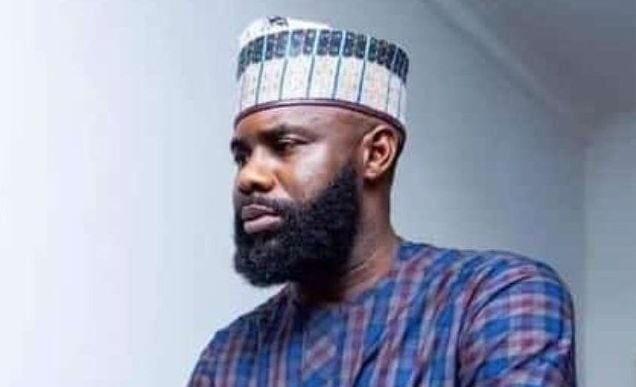

On a hot February afternoon in 2023, Haruna Mohammed Salisu was shoved into a police van on the orders of the Bauchi governor. Moments earlier, the 34-year-old publisher of WikkiTimes — a small investigative news outlet in Bauchi state — was interviewing voters during the presidential election. He was arrested and accused of “inciting public disturbance” simply for doing his job. As armed officers hauled him away, Salisu realised this was a price he had to pay for telling uncomfortable truths in today’s Nigeria.

Hounded, beaten and thrown into jail for five days, Salisu was later released on bail. His alleged crime? Reporting about local women protesting against a governor.

“They wanted to silence me forever,” Salisu recalled. “But surrendering to a bully means they could silence all of us– and that is very dangerous.”

Advertisement

The ordeal of that week – detained in a crowded cell, his phone confiscated by police in defiance of a court order – was only an escalation of what has become a persistent campaign to intimidate and suppress WikkiTimes and its journalists.

Founded in 2018 to cover Northern Nigeria’s news desert areas, WikkiTimes has stood at the forefront of watchdog journalism amidst a quiescent media environment. The outlet consistently exposes corruption, abuse of power and injustice in places overlooked by the mainstream media. From uncovering election malpractices and dubious constituency projects to investigating terrorism financing and illegal mining, WikkiTimes’ reporting has repeatedly rattled the powerful.

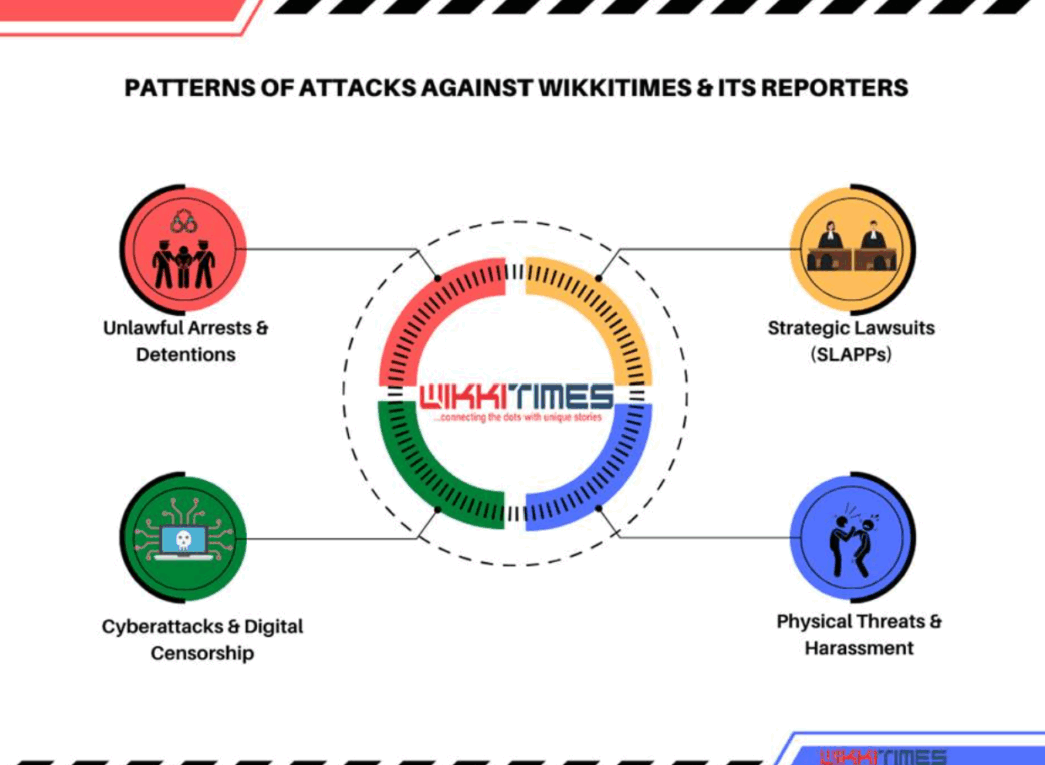

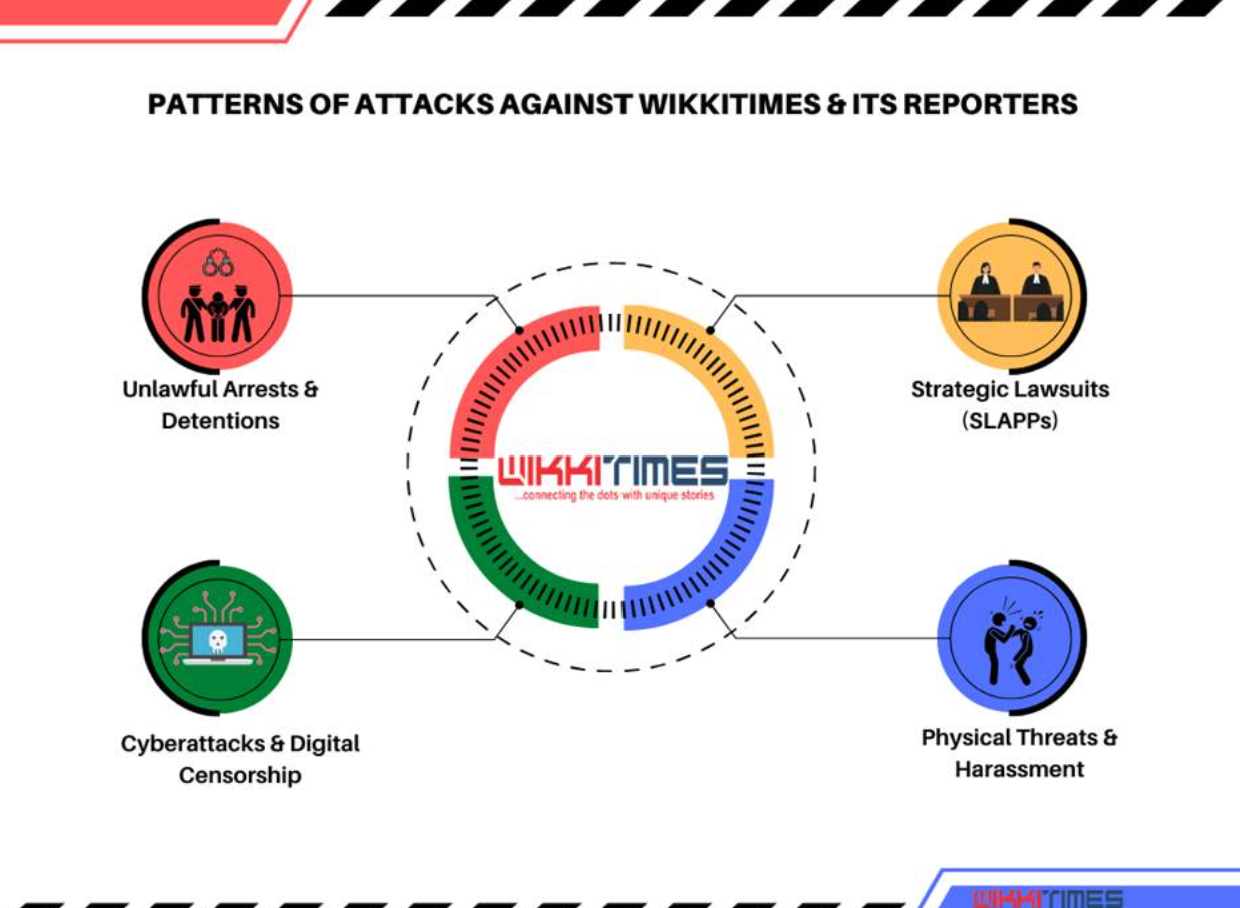

But that commitment to truth has come at a high cost. In recent times, WikkiTimes and its staff have faced an onslaught of retaliation. From strategic lawsuits and arrests to cyberattacks, harassment, and threats — all seemingly coordinated to muzzle the news platform.

Advertisement

Those exposed by WikkiTimes’ reporting have often chosen repression over accountability. Each hard-hitting investigation is met with pushback driven by personal vendetta.

“They resort to retaliation rather than seeking redress in courts,” Salisu noted.

“It has become a pattern now; some form of punishment follows every major story we publish. The son of Bauchi state governor once publicly vowed eternal enmity against me for a story that was yet to be published. His father gave me the same treatment, because when I was interviewing the women, they arrested me, and later charged me to court for a story that was not yet published.”

Family members of a former WikkiTimes editor, Yakubu Mohammed, received anonymous threats after WikkiTimes published an investigation. The message is clear: journalism that confronts the mighty is being treated as a crime in some parts of Nigeria.

Advertisement

THREATS, INTIMIDATION, AND PERSONAL HARASSMENT

The attempts to cow WikkiTimes’ journalists have been intensely personal. Not long ago, a WikkiTimes report exposed alleged terrorism funding and illegal gold mining in Niger state – a story that implicated a Chinese mining company, local officials and businessmen. Rather than investigate the claims, those fingered responded with fury and threat. They slammed WikkiTimes with a N10 billion defamation lawsuit, hoping to bury the allegations in court. Such frivolous legal threats have become commonplace.

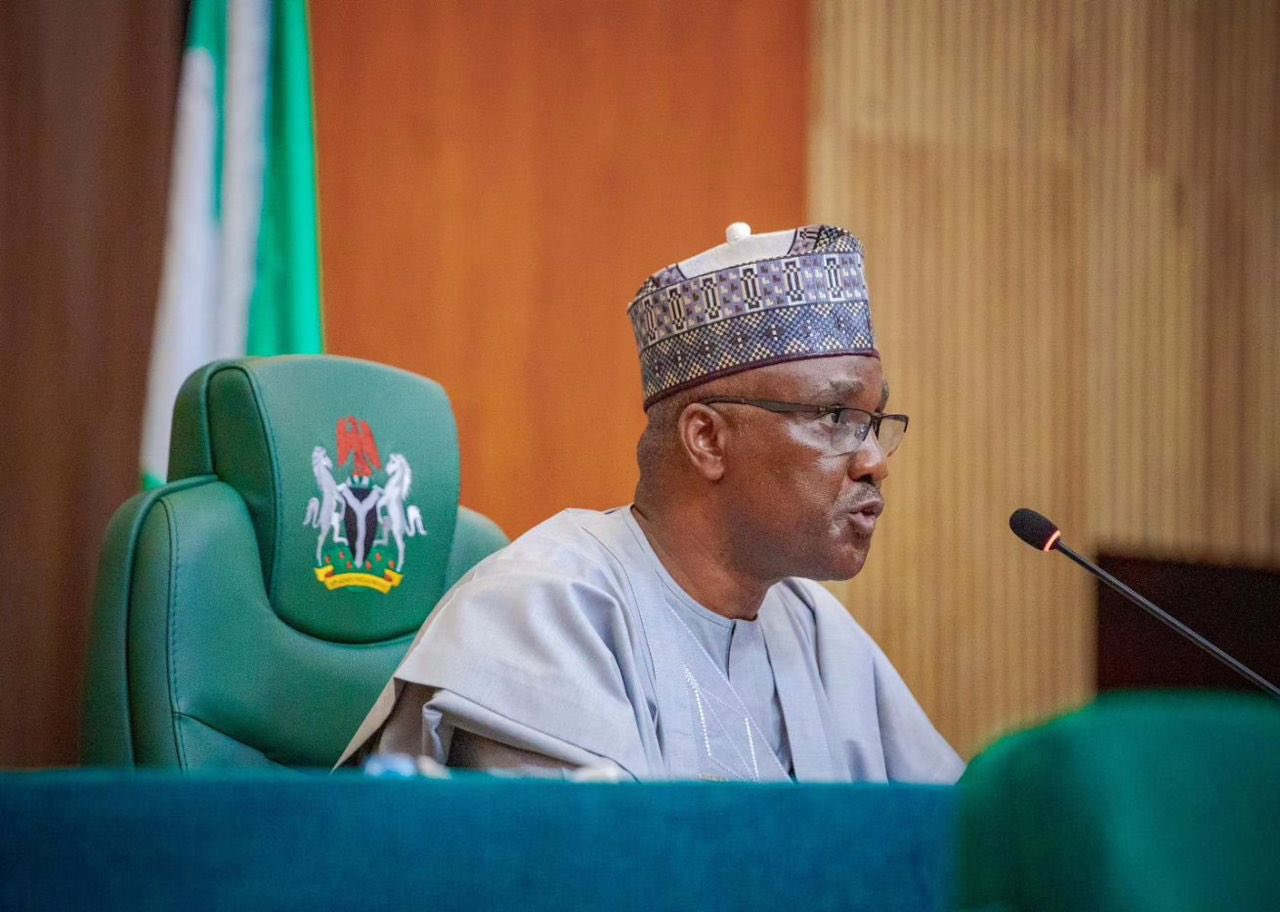

Another investigation detailed how a Saudi Arabia-funded charitable hospital in Bauchi, the Makkah Eye Clinic, was extorting patients and evading taxes in violation of its non-profit mandate. The charity responded by issuing a death threat to WikkiTimes’ publisher, dragging the outlet to court and demanding ₦1 billion in damages. In early 2022, after WikkiTimes published an exposé on a ₦1 billion model school project that never materialised in Bauchi, Yakubu Dogara, former house of representatives’ speaker, hit back with a ₦2 billion libel suit. Dogara’s lawsuit accused WikkiTimes of defaming him by reporting that funds for a school in his constituency had been misappropriated. Notwithstanding, the WikkiTimes defended the factual accuracy of the report. The Media Foundation for West Africa condemned Dogara’s action as a “vexatious legal assault” aimed at intimidating the press.

Advertisement

Since 2020, WikkiTimes has faced at least nine such SLAPP suits (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation) from politicians, businessmen and institutions named in its reports. These cases are not really meant to be won in court – they are intended to drown the young outlet in paperwork, legal fees and stress.

“As a small platform, it is difficult to hire lawyers, fund several trips by our reporters to attend court hearings,” Haruna Mohammed said. Kamal Idris, a reporter who was a co-defendant in the Makkah Eye Clinic case, shared the same view.

Advertisement

“The court cases were an eye-opener… but draining. We don’t have the resources that politicians or companies have,” Kamal said. “Each lawsuit, even if frivolous, saps time and money that could be spent on journalism.”

Physical intimidation has come hand-in-hand with legal harassment. In June 2023, WikkiTimes’ newsroom in Bauchi was shaken by a new scare. The outlet had reported on threatening text messages received by Hussaini Musa Gwaba, an opposition politician who mysteriously died soon after. The story noted that a Bauchi federal lawmaker had been unhappy with Gwaba’s appointment as local party chairman, implying a potential motive in the threats and raising questions about Gwaba’s death. The lawmaker petitioned the police, accusing WikkiTimes of “cyberstalking” him.

Advertisement

Police officers visited the WikkiTimes office in Bauchi and detained publisher Haruna Salisu and reporter Kamal Idris for 48 hours without any court warrant.

“Our detention was a nightmare,” Kamal recalled. “We were tortured from the moment we were put in the cell. The cell was filthy, and we had to sleep and urinate in the same place. There were only two dirty buckets for us. The air was rank. By the time we got out, I couldn’t focus on work for days because of the trauma.”

Advertisement

During those two days behind bars, the journalists said they were beaten and threatened by violent inmates – an action they believe was pre-planned.

“They put us in with deadly thugs and even terrorists,” said Salisu, describing the cell in Bauchi’s State Criminal Investigation Department where they were held. Eventually, both were charged under Nigeria’s Cybercrime law, referencing the article on Gwaba’s death. A court later dismissed the case.

The climate of hostility forced WikkiTimes’ editor, Yakubu Mohammed, to flee Bauchi in 2023. While Salisu languished in detention after the election-day arrest, word reached Yakubu that authorities were planning to arrest him next. The next morning, Yakubu packed up and quietly left Bauchi for his own safety.

“Your identity is known by all the local actors you report on,” Salisu explained the risks inherent in subnational journalism. “It’s easy for them to profile you and trace your location. Very few of us do this kind of work where we operate, so we could easily be profiled and targeted.”

In Yakubu’s case, relocation was the only way to avoid becoming the next target. Other WikkiTimes reporters have also periodically gone into hiding or moved residences after receiving warnings that “the big men are after you.”

SLAPPs AND LEGAL WARFARE AGAINST THE OUTLET

The use of lawsuits as weapons to weaken WikkiTimes has intensified in the past two years. Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs) – suits filed not to seek justice but to silence critics – have been deployed repeatedly against the outlet. The pattern often repeats: WikkiTimes publishes a damning investigation; a powerful figure it implicates responds with a libel suit or a criminal defamation charge; a hefty sum in damages is claimed, sometimes alongside arrest warrants or police interrogations to scare the outlet’s journalists.

There are many crippling lawsuits against WikkiTimes. For instance, after revealing that a Bauchi charity hospital (funded with support from Saudi Arabia) was charging poor patients high fees and mistreating staff, the hospital’s parent foundation sued the outlet for ₦1 billion, alleging defamation. The case still lingers. Media rights groups helped WikkiTimes mount a defence.

In late 2022, Abdullahi “Baba Iyali” Abdulkadir, a federal lawmaker from Bauchi, dragged WikkiTimes to court not even for its own journalism, but for republishing an investigative report by another outlet. The investigation – originally from another outlet – alleged that Abdulkadir facilitated a dubious road construction contract that siphoned public funds. WikkiTimes ran the story as part of a content-sharing partnership. In retaliation, the legislator sued WikkiTimes, claiming the report “tarnished his image” among constituents. He demanded damages and an injunction against further circulation of the story.

In April 2024, WikkiTimes published a blockbuster story by reporter Yawale Adamu detailing how a Bauchi lawmaker colluded with a local contractor to divert millions of naira from constituency projects. Rather than address the documented claims, Soro (through an associate) filed criminal complaints for defamation and “injurious falsehood” against WikkiTimes. In September 2024, a Bauchi magistrate issued a bench warrant for publisher Haruna Salisu after he failed to appear at a court hearing on the matter. Salisu had fled Nigeria and was already in the US pursuing postgraduate studies.

The reporter, Yawale Adamu, was hauled into court to face the charges, which carry up to five years in prison.

“My only weapon was the truth, backed by evidence. But in Nigeria, the truth is dangerous,” Yawale said, as his trial on the Soro case continues. Soro himself has stayed mostly silent on the allegations, despite CPJ’s calls for the charges to be dropped. Meanwhile, he also lodged a civil suit demanding that WikkiTimes retract the story, apologise publicly, and pay about ₦2.5 million in damages and legal fees.

In Kano state, a businessman went to a magistrate court after a WikkiTimes article exposed irregularities in a multi-million naira school construction project he handled.

In an unusual move, the court issued a criminal summons against WikkiTimes over the report. The story detailed how six companies built substandard classrooms across three districts. The case, filed ex parte without WikkiTimes’ knowledge at first, was clearly intended to pressure the outlet into silence. Local journalists in Kano said such private prosecutions are an emerging form of harassment, exploiting magistrate courts to intimidate the media.

These lawsuits form a broad legal offensive against WikkiTimes. None of the suits has succeeded on the merits, but success in court isn’t the point.

“They want to exhaust us financially and psychologically,” Salisu said. Fighting on multiple legal fronts has drained the outlet’s meagre resources and forced its journalists to spend almost as much time in courtrooms as in the field. It’s a classic SLAPP strategy – intimidate the press into self-censorship through sheer attrition.

A DIGITAL WAR ON TRUTH

When legal and physical intimidation haven’t worked, WikkiTimes’ adversaries have turned to digital harm. The outlet has weathered waves of cyberattacks and online harassment seemingly timed to coincide with its most explosive stories. In April 2025, WikkiTimes’ website came under more than 400 coordinated cyberattacks within a 48-hour period.

The deluge of malicious traffic and hacking attempts knocked the site offline repeatedly, disrupting the publication of new stories and temporarily cutting off readers.

“Pages wouldn’t load, our admin panel was locked out, and we saw traffic from bots we couldn’t trace,” recalled Ibrahim Salisu, the outlet’s technical support lead, who battled around the clock to get the site back up. “It felt like someone was intentionally trying to silence us or wear us down digitally.”

The persistence of the April attack was what unnerved him most. “It wasn’t just a random spike – it was calculated, coming at us from different directions,” he said.

It wasn’t the first such incident. In April 2023, hackers breached WikkiTimes’ backend and wiped its story database, erasing several published articles before the site could be restored from backups. And in November 2022, the outlet’s Facebook page – which had tens of thousands of followers – was suddenly taken down by Facebook after WikkiTimes ran a damning investigation into a cover-up by Bauchi police commissioner.

The story in question exposed how a former Bauchi police commissioner allegedly helped the state’s ex-information commissioner evade justice after the latter shot a friend dead in a bar. Within days of publishing that report, WikkiTimes’ Facebook presence vanished. The team suspected orchestrated reporting of their page for “violation of standards” by loyalists of those implicated. Facebook never clarified why the page was removed.

Beyond direct cyberattacks, WikkiTimes has been hit by disinformation campaigns aimed at discrediting its work. In one case, a doctored video circulated on WhatsApp and Twitter, accusing WikkiTimes of receiving foreign funding to destabilise northern Nigeria’s stability and elites. The video – a montage of spliced clips with a fake voiceover – suggested the outlet was part of an international plot against the north, playing on popular conspiracy tropes.

“It was absurd, but some people believed it,” said Salisu, noting that the disinformation emerged soon after WikkiTimes published a series of articles on high-profile corruption in northern states. Online trolls have also hounded the outlet’s reporters on social media, bombarding them with slurs and accusations of being “traitors” or “paid agents” whenever a new investigation is published. These coordinated smear campaigns seek to tarnish WikkiTimes’ credibility among the local audience. It’s a tactic in regions where social media rumours can spread faster than facts.

All these digital assaults, from hacking to propaganda, form part of the new playbook of censorship. As Salisu Ibrahim observed, “These kinds of attacks are becoming more common, especially against media organisations that speak truth to power.” For WikkiTimes, defending against cyber warfare has now become as important as digging for documents or cultivating whistleblowers.

“We expected anger and maybe a lawsuit or two,” said Haruna Salisu of the fallout from their stories. “We didn’t expect them to try to delete our journalism from the internet or to poison the information space with lies about us. It’s a different level of threat.”

SOLIDARITY AND THE STRUGGLE FOR PRESS FREEDOM

WikkiTimes’ plight has not gone unnoticed. Press freedom advocates in Nigeria and abroad have rallied, in cash and kind, to support the outlet. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Media Rights Agenda (MRA), the International Press Centre (IPC), the Media Defence UK, The Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism, Forbidden Stories, Center for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID), The Wole Soyinka Center and the Media Foundation for West Africa (MFWA) and many others have either issued statements or bankrolled WikkiTimes to confront its SLAPP lawsuits. They have also condemned the arrests, lawsuits and cyberattacks against WikkiTimes. These voices explained that an attack on one journalist or outlet is seen as an attack on the broader media and the public’s right to know.

Yet beyond public statements and legal advocacy support, the outlet’s staff continue to operate under tremendous pressure, often looking over their shoulders. Some have taken self-defence training; others vary their daily routes or use secure communications to avoid surveillance.

“We have changed office locations more than three times within two years to avoid being tracked and intimidated by police and other powerful forces. That has come at a heavy cost on WikkiTimes,” Aminu Adamu, the editor, said.

WikkiTimes’ modest revenues (largely from grants and donations) are being drained by legal fees and cybersecurity costs. “Every lawsuit means money for lawyers instead of reporting. Every cyberattack means money for IT security instead of field investigations,” the publisher said, describing how resources are diverted just to keep the outlet afloat and safe.

Nigeria’s broader climate for journalism only compounds the problem. The country consistently ranks poorly on global press freedom indices. In 2024, Reporters Without Borders placed Nigeria 112th out of 180 countries on its World Press Freedom Index – an improvement from 123rd the year before, but still deep in the red zone.

This year, the ranking slipped back to 122nd, reflecting a decline in safety for journalists and growing official intolerance for dissent. Attacks on media houses like WikkiTimes are a key reason Nigeria’s press freedom metrics remain abysmal. Nearly 40 Nigerian journalists suffered harassment, arrests or assaults in 2023 alone, according to a media rights monitor, with security agencies and political thugs frequently implicated.

Media experts argue that the struggle of WikkiTimes is emblematic of a larger battle for press freedom in Nigeria. Hamid Adamu Muhammad, a mass communication scholar at North Eastern University, Gombe, said the pattern of harassing journalists for exposing the truth is as uncivilised as it is dangerous.

“It is the responsibility of journalists to expose what organisations and governments are doing that is not right,” he said.

Global press freedom monitors echo that sentiment. They point out that impunity for crimes against journalists, gender-based online attacks, and targeted digital surveillance are three of the most pressing threats to free journalism today – and that violence is the most extreme form of censorship. In other words, when telling the truth leads to one being beaten, jailed or financially ruined, it’s not just a personal tragedy but a society-wide alarm.

“Journalism can only be exercised freely when those who carry out this work are not victims of threats or physical, mental or moral attacks or other acts of harassment,” it said.

Back in Bauchi, the WikkiTimes team soldiers on. They have learned to be resourceful and resilient – migrating servers when they come under attack, backing up content in multiple locations, fighting their battles in court during the day and chasing stories by night. Their determination has yielded small victories: public interest in their work is growing, and some corrupt schemes they exposed have been halted by embarrassed authorities. Each win, however minor, bolsters their resolve.

“We owe it to our people to keep going. If we don’t speak for our people, who will? We can’t let these guys get away with impunity,” Haruna Salisu declared.

This report is produced by WikkiTimes in collaboration with the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) as part of a project documenting issues focused on press freedom in Nigeria.