BY FREDRICK OTIENO

For decades, Africa has proposed the inclusion of a dedicated agenda item in climate negotiations to address its special needs and circumstances related to climate change and development.

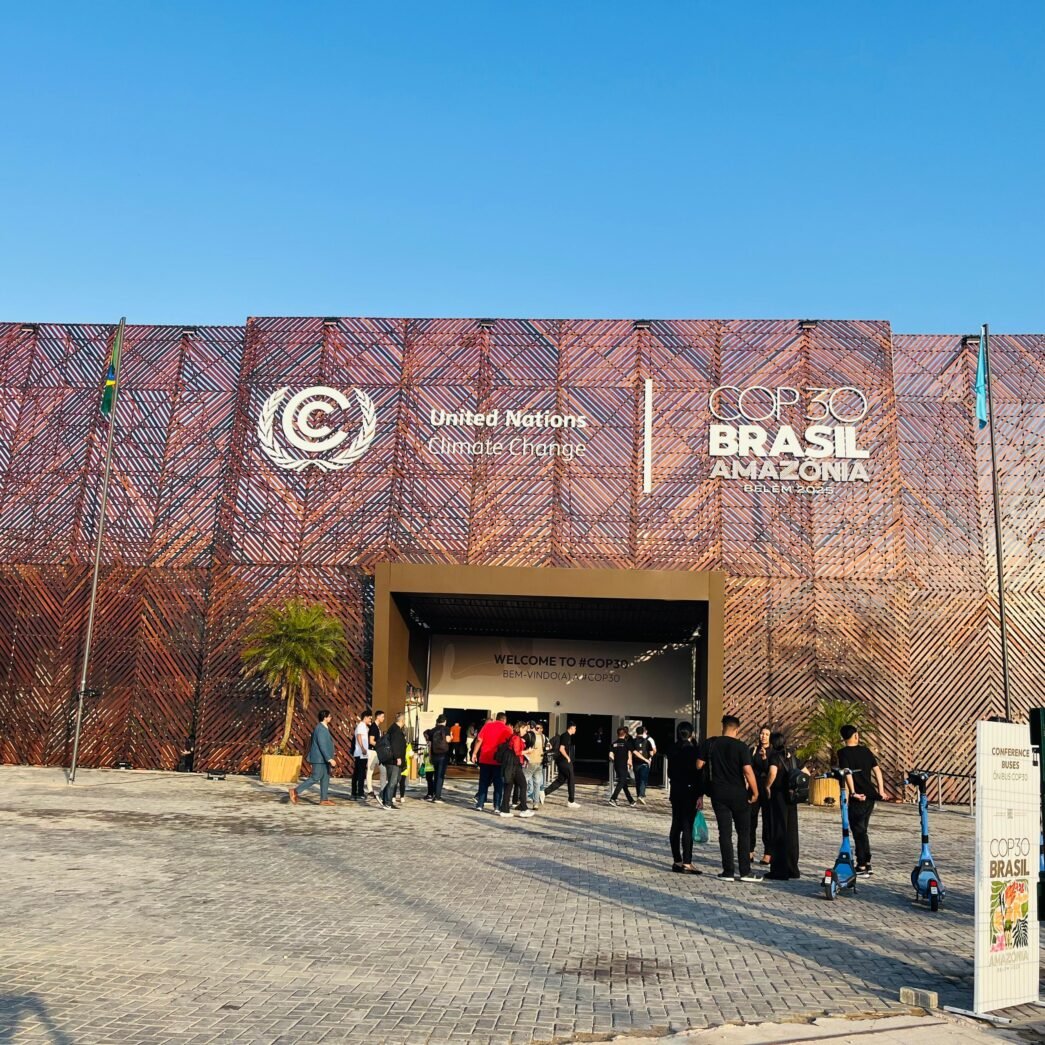

Africa’s civil society organisations wanted the proposal to be an agenda item at the ongoing COP30 in Belém, Brazil, arguing the push is based on Article 4.1 of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Part (e) of the article calls for cooperation to support climate-vulnerable countries, including Africa, to develop appropriate adaptation measures to protect coastal areas, water resources and agriculture. It further calls for cooperation to rehabilitate areas affected by drought, desertification, and floods.

Advertisement

Various COP decisions have acknowledged the uniqueness of Africa’s situation. At COP27 in Sharm-el-Sheikh, for instance, the outcome highlighted African needs and vulnerabilities by establishing the Loss and Damage Fund to support frontline communities in Africa and elsewhere in the developing world.

At COP28, world countries agreed on the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience as part of the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA). The framework specifically covers priority areas such as water, food, health, and ecosystems and the vulnerabilities of these sectors in many African countries.

Additionally, COP28 dedicated a day to Africa, highlighting the significant climate finance gap and the urgency of adaptation finance for the continent.

Advertisement

Africa’s special needs and special circumstances

Out of the 46 Least Developed Countries (LDCs) in the world, 33 are in Africa. These countries have low income per capita, high poverty rates, and structural weaknesses in human and economic resources. The countries rely heavily on agriculture, which is sensitive to climate impacts. At 600 million, Africa has the highest number of people without access to electricity.

At the same time, all African countries are considered developing, faced with multiple, overlapping climate and fiscal vulnerabilities. Many of them lack the institutional capacity necessary to drive robust climate action and spur development. A One Campaign 2025 analysis shows that 20 African countries are at risk of debt distress, while 47 African nations account for 52 percent of those indebted to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Africa is warming faster than the rest of the world

Advertisement

The continent is responsible for less than 4 percent of historical greenhouse gas emissions, which caused climate change. The continent is, however, warming up faster than the global average, according to the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO). This is largely due to Africa’s geographical location.

In recent decades, this rise in temperatures has triggered droughts, floods and cyclones, whose frequency and intensity have multiplied, putting at risk the lives of more than 1.5 billion people, or 17 percent of the world population, who live on the continent.

To address the socioeconomic impacts of climate change in Africa, the WMO says the continent needs between $30 and $50 billion annually for the next decade. But the current financial flows to Africa tell a different story.

In 2023, developing countries received only $26 billion for adaptation, down from $28 billion the previous year. While adaptation needs are growing, the climate finance gap is widening by the year, further shrinking the adaptive capacity of the African people and economies.

Advertisement

Why the subject is a political landmine

Yet the proposal to recognise Africa’s special needs and circumstances has been a political and technical landmine in climate negotiations. Developed countries and, in some instances, several developing countries, have stalled progress on the proposal.

Advertisement

They argue that this recognition is dangerous as it could set a political precedent, with other regional blocs demanding similar consideration. To them, groups such as the LDCs and Small Island Developing States (SIDS) already represent unique circumstances and, therefore, recognising Africa’s situation might create a ‘‘new category of Parties’’.

Moreover, developed countries insist that all elements that constitute Africa’s special needs and circumstances are captured in the UNFCCC agenda, including climate finance, adaptation and technology support to facilitate the transition to a low-carbon economic regime.

Advertisement

The main concern, though, is the financial implications of such recognition. Wealthy nations have often felt that acknowledging Africa’s special needs and circumstances through a formal agenda could strengthen calls for region-specific finance quotas and technology transfer obligations. This would effectively reinforce the CBDR-RC principle that developed countries often seek to minimise or move away from.

Those opposed to this recognition also argue that African climate and development issues are already “mainstreamed” through existing bodies and agenda items, including the LDC Expert Group and Adaptation Committee, with substantial representation.

Advertisement

They fear, therefore, that including Africa’s special needs and circumstances in the agenda would not only ‘‘inflate the agenda’’ but also overload negotiators and secretariat resources, they say.

Interestingly, the divergence is also internal, with some developing countries and developing country groups either neutral or non-committal, fearing that such recognition might ‘‘create a hierarchy’’ among developing countries and potentially divert attention and resources from LDCs and SIDS. This divergence of opinion weakens Africa’s push.

This is a matter of justice and fairness

African civil society organisations concur that recognising Africa’s situation is both justified and necessary ‘‘to ensure the effective and equitable implementation of the Convention and the Paris Agreement.’’ They disagree that this proposal would create new legal categories of Parties or impose new climate obligations on others.

Such recognition can be achieved without amending the Convention by simply acknowledging Africa’s specific context and providing a structured space within the UNFCCC process to address the continent’s distinct implementation challenges.

The sentiment shared by many Africans is that a dedicated agenda item would bring coherence and efficiency in addressing the continent’s issues, currently scattered in multiple agenda items on adaptation, finance, capacity-building, and response measures.

As currently designed, the UNFCCC process has no ‘‘integrative mechanism’’ to track overall progress on Africa’s climate and development priorities. This is where a single agenda item comes in: to consolidate these discussions, enhance coordination, and reduce duplication.

Establishing this agenda item at COP30 doesn’t mean new financial commitments or obligations for developed countries. Rather, it would allow Parties to assess how the current obligations of the Convention and Article 9 of its Paris Agreement have been implemented.

Not too much to ask

This is important to improve the efficiency and transparency, especially in the delivery of finance to Africa through existing finance mechanisms, including the Green Climate Fund, Adaptation Fund, and Loss and Damage Fund.

Rather than dividing countries, the proposed recognition enhances cooperation by providing a practical platform for partnerships between Africa and development partners on technology, capacity-building, and just transition initiatives.

By recognising Africa’s unique situation, COP30 will have made its specific context more visible, making it possible to address the continent’s challenges in a more coordinated and coherent manner. The net effect of this would be to boost global solidarity in supporting Africa and delivering support to the continent’s hungry, energy-poor, and climate-vulnerable population.

More importantly, this recognition would complement, and not compete with, existing recognition of LDCs and SIDS. After all, many African countries share similar threats and constraints.

For a continent that’s most affected but least responsible for climate change, asking for recognition and support to pursue sustainable development and resilience on fair terms isn’t too much to ask.

Fredrick Otieno is a project officer at Power Shift Africa

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.