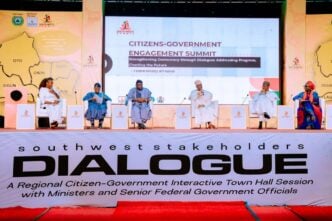

Nnamdi Kanu (in white) | File photo

BY VICTOR OPATOLA

There are moments in history when the choices of a single individual come to symbolise far more than their personal fate. In Nigeria today, Nnamdi Kanu’s decision to represent himself in court is one such moment. His trial carries implications beyond himself. It touches on questions of national identity, justice, and trust in Nigeria’s institutions. The law, for all its flaws, remains a human instrument. It bends toward those who know how to use it and may humble those who underestimate it.

Nnamdi Kanu’s case is not hopeless; anybody who has bothered to read the amended charges against Nnamdi Kanu will agree to that. Out of the 15 amended charges initially filed against him, eight were struck out under Justice Nyako for failing to disclose any offence. That leaves seven remaining counts, ranging from alleged acts of terrorism to illegal importation of a transmitter and incitement through radio broadcast and other charges. Now, the remaining charges, without pre-empting the court, are also severely contestable. For instance, the charge regarding the unlawful import and labelling of transmitters is also severely contestable.

Similarly, the terrorism-related counts and others, especially those relating to broadcasts allegedly made in London but received in Nigeria, face a heavy evidentiary burden. The prosecution must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the broadcasts were not merely expressions of opinion but directly incited or caused specific acts of violence within Nigeria. It must also link those utterances to the actual burning of government properties, attacks on security personnel, or disruption of civil life, and direct or circumstantial evidence that whoever does all these acts in furtherance of his instructions.

Advertisement

Especially given that although he has been incarcerated and even mentioned dissociating himself from many acts of IPOB, yet many of them continued. There cannot be any gap in between. This is not an easy hurdle to cross. Nigerian courts, like others in the common law world, treat “incitement to violence” with a very narrow lens: intent must be clear, causation must be direct, and the nexus between words and criminal acts must be unbroken. Any reasonable doubt at all, any ambiguity, must be resolved in the accused’s favour. For instance, in the case of the burning of government properties in Lagos, it must be strongly proven that he directed it, and such persons acted under his instruction; and that nothing else at that period could have led to such burning or other people burning the properties.

From all legal indications, therefore, Kanu has at least a good higher than average chance of defeating the remaining counts if his defence is properly coordinated, professionally argued, and strategically managed. That chance becomes slimmer, dramatically so, as he insists on standing alone in court without the guidance of lawyers experienced in criminal litigation.

Consider also the witnesses Kanu has proposed to call: governors, ministers, military chiefs, and even foreign observers. It is unclear how such figures would directly advance his defence. None of them was present when the alleged broadcasts were made or when the transmitter was imported. None can testify to his intent at the time of those utterances. Criminal law is not impressed by status or symbolism; it is anchored on facts, evidence, remoteness and direct relevance. A parade of prominent names may create spectacle, but not acquittal.

Advertisement

More critically, representing oneself strips a defendant of the strategic buffer that trained counsel provides. Lawyers act as shields, filtering emotion, tempering impulse, and ensuring that every statement aligns with legal defence. In high-stakes trials like this, one careless word can be interpreted as an admission or a confession. Kanu’s insistence that “there is no charge against me” may sound defiant, but it risks being construed as a refusal to defend, a procedural surrender, not a triumph.

Criminal proceedings are not only about guilt or innocence; they are about the process through which the state exercises power. Every misstep by the accused can legitimise that power. Even if there are assurances of possible political resolution or pardon in the future, prudence demands that he tread carefully. Political promises are not legal defences; they can evaporate overnight. Even if he hopes for a political solution, it is wise to vigorously defend this matter first, and either way political solution may come.

It is not too late for him to retrace his steps. The court has given him time. The law still offers him protection. But if he continues down the path of self-representation, he risks turning a winnable case into a less winnable one.

Opatola Victor, the national coordinator, Lawyers for Civil Liberties, can be reached via [email protected]

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.