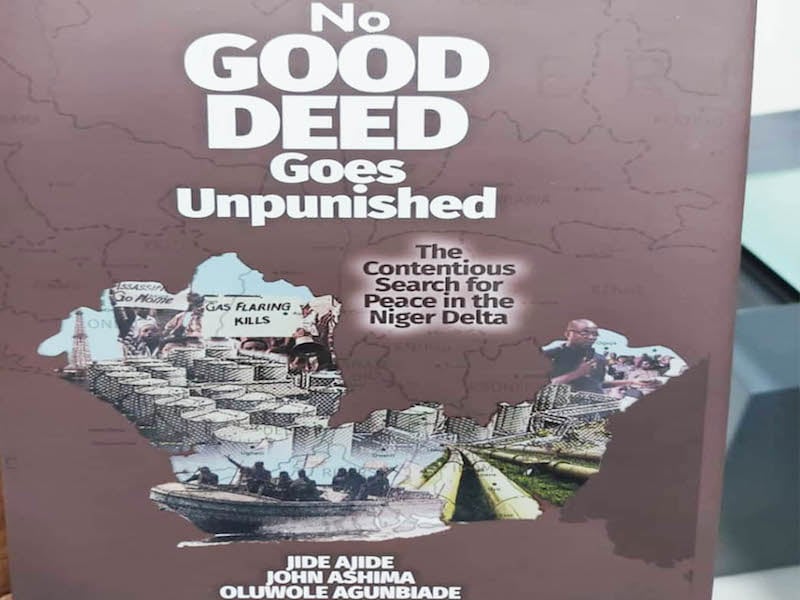

The cynical axiom, “No good deed goes unpunished,” usually describes individual disillusionment. However, as documented in the compelling non-fiction analysis, No Good Deed Goes Unpunished: The Contentious Search for Peace in The Niger Delta by Oluwole Agunbiade, John Ashima, and Jide Ajide, this phrase captures the fundamental complexity of social issues in Nigeria – a nation where acts of charity and corporate generosity often collapse under the weight of historical context, structural dysfunction, and competing expectations.

The book’s deep dive into the oil-rich Delta, a region where resource wealth coexists with profound poverty, reveals a microcosm of the paradoxes that plague national development. The authors, leveraging their extensive experience in the oil sector, demonstrate why even the most expensive corporate social responsibility (CSR) programmes can invite more conflict than commendation.

The Broken Bridge of Charity and Compensation

In the Delta, and by extension, much of Nigeria, a “good deed” is rarely seen as an isolated act of goodwill; it is viewed through the prism of owed compensation. Agunbiade et al. show that when an International Oil Company (IOC) drills for crude, the communities endure environmental degradation and a sense of historical injustice. Therefore, when a company offers charity – perhaps by building a school or a health clinic- it is often not met with pure gratitude. Instead, it is frequently seen as a partial payment on an ancient, unpaid debt.

Advertisement

This creates an immediate clash with the demands of genuine corporate responsibility. What starts as a simple effort to improve lives often disintegrates because the community’s expectation is not merely the project itself, but holistic transformation. The company, by intervening, steps into the large vacuum created by a lack of government accountability, effectively becoming the sole, visible source of provision. The resulting pressure, as documented through the authors’ case studies, is overwhelming and leads to the “punishment” of the initial generous act.

Entitlement and the Paradox of the Extended System

The concept of entitlement is one of the most volatile factors analyzed in the book. It stems from both justified grievances (like environmental damage) and cultural pressures. This phenomenon is severely amplified by the powerful extended family support system. This system, while being the bedrock of Nigerian resilience and survival, simultaneously creates unmanageable dependencies.

Advertisement

As documented by the authors, when an individual or a community leader receives a benefit (a scholarship, a contract, or even just access to a corporate facility), they are instantly expected to share that benefit vertically and horizontally across their entire network. The success of one is immediately the expectation of hundreds. The weight of meeting these demands embodies the impracticability of meeting them. Failure to provide for everyone is interpreted as a selfish betrayal, leading to internal community fracturing and open hostility toward the source of the initial “good deed.”

The Vicious Cycle of Fear and Criminality

When high expectations, fueled by both need and perceived entitlement, collide with resource scarcity, the resulting disappointment can quickly manifest as criminality. The book details how failed CSR projects lead directly to pipeline vandalism, illegal bunkering, and sabotage. The community, unable to hold their own mismanaged leaders or the distant government accountable, targets the accessible entity: the oil company.

This environment fosters a deep state of fear. Companies fear making new investments, knowing the effort might be “punished.” Local leaders fear receiving money, as they know they will be targeted, extorted, or blamed for any failure, often choosing to be corrupt or stepping down to avoid the consequences. As Agunbiade et al. argue, this paralysis ensures that development stagnates, perpetuating the very problems the original good deed sought to solve.

Advertisement

Is There a Way Out? Embracing Equity and Partnership

The relentless cycle detailed in No Good Deed Goes Unpunished is disheartening, yet the authors suggest the situation is not hopeless. The antidote lies in shifting the paradigm from charity to equity, transparency, and shared responsibility.

The way out requires a collective move away from the unsustainable model of corporate philanthropy (the “good deed”) toward:

1. Accountability from the State: The government must step up to its constitutional duties, relieving the IOCs of being the sole source of development.

2. Shifting Corporate Strategy: Companies must move toward genuine partnerships that build local capacity and economic independence, as opposed to creating dependency.

3. Managing Expectations: Open, honest dialogue must reset communal expectations to practical, achievable goals, finally breaking the psychological barrier of entitlement rooted in historical debt.

Nigeria’s complex social landscape makes the path difficult, but by confronting the reality that “no good deed goes unpunished,” stakeholders can use the critical insights provided by Agunbiade, Ashima, and Ajide to design systems that ensure good intentions lead to genuine, sustainable reward.

Advertisement

Adebawo is an accomplished business leader and communications expert with extensive experience in the oil and gas industry. He currently serves as the General Manager of Government, Joint Venture, and External Relations at Heritage Energy. Adebawo is also an author, scholar, and ordained minister, known for his writings on socioeconomic issues, strategic communication and leadership.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.