BY OPATOLA VICTOR

In the past few weeks, social media, especially Twitter, has been full of arguments about lawyers’ fees, with many people insisting that legal fees for services are “unjustifiable”, “unnecessary,” or outright “unwarranted.” Some even went as far as questioning the actual relevance of the legal profession. The profession and the judiciary indeed have their humongous and deep-rooted challenges, especially the terrible and people’s justified lack of faith in the judiciary, but what stood out most, however, was not what the critics said but what the public did not say.

In all the discussion, not a single non-lawyer who had ever benefited from proper legal work came forward to say, “A lawyer saved my property, saved my business, protected me from police abuse, defended my rights, saved my life, and if I had the money, I would have paid anything.” Not one person who had enjoyed a free legal defence, a bail, a contract rescue, a last-minute injunction, or a life-saving fundamental rights application came out to say even a single sentence of appreciation or defence of the profession. This silence is not accidental; it is the product of a deeper historical, cultural, and generational conditioning that has shaped how Nigerians perceive lawyers and the value of legal services.

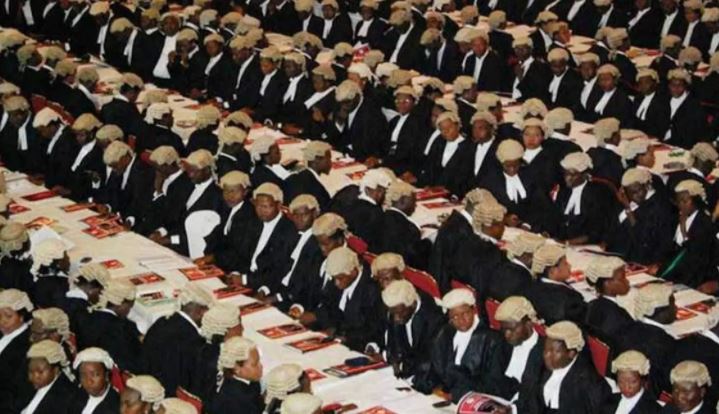

To understand the foundational reason (while not even neglecting other factors) why Nigerians casually dismiss lawyers’ fees, you must understand how the legal profession began in this country. Legal practice in Nigeria did not originate as a commercial professional service like accountancy or engineering. It began as a political, liberation-oriented mission tied directly to the colonial struggle. The earliest Nigerian lawyers, figures like Sapara Williams, H.O. Davies, Obafemi Awolowo, and others, were not primarily seen as “professionals for hire”.

Advertisement

They were seen as freedom fighters, intellectual warriors who used law to challenge colonial injustice. Many of them mixed legal practice with political activism, mobilisation, social justice campaigns, and anti-colonial agitation. This gave Nigerians their first impression that lawyers were not businesspeople; they were champions of the oppressed, whose work was moral, patriotic, and often free, cheap or symbolic.

Many of these early legal icons did tremendous work, but one unintended consequence was that they created a cultural template. They were admired not because they drafted commercial agreements or did transactional work, no, they were admired because they went to court against the colonial government, defended protesters, challenged oppressive ordinances, and did it for little or no pay. They built their political careers on reputation, not on legal fees. Many used free representation as a foundation for popularity and influence. That ingrained a dangerous, long-lasting societal belief: “Lawyers help the people, not charge the people.”

When independence came, this culture became even stronger. The new Nigerian state was turbulent, and lawyers became the natural defenders against unlawful detention, political intimidation, and government excess. The 1960s, 1970s, and especially the long military era (1966 – 1979, then 1983 – 1999) created a new wave of activist-lawyers whose work was inherently free, because the clients they fought for – journalists, students, protesters, civilians -had no money to pay. The most respected lawyers of that era, Gani Fawehinmi, Kanmi Osobu (people’s law), Alao Aka-Basorun, etc, built legacies of challenging state abuse without charging their clients or at least a pittance. Even younger lawyers then learned the trade by doing pro bono habeas corpus cases, fundamental rights cases, and cases against police or military detention.

Advertisement

Thus, two generations of Nigerians grew up seeing lawyers as heroic defenders of human freedom, not as commercial service providers. The public memory of lawyering became romanticised: lawyers were the ones to call when someone was arrested unlawfully, detained by soldiers, or threatened by the government. Lawyers fought dictators, not negotiated business deals. Lawyers drafted bail applications, not purchase agreements. Lawyers attended protests, fought at police stations for the right of clients not to sit on high-level board meetings. Lawyers filed fundamental rights cases, not important documentation, and even if they did, it would be a cheap payment.

This left a powerful psychological imprint on Nigerian society: Lawyers are saviours, not service providers.

So when democracy returned, and Nigeria began evolving into a modern economy with commercial, corporate, and regulatory needs, the public perception of lawyers did not evolve accordingly. The economy changed, but the cultural memory of “lawyers as freedom fighters” and “free or cheap service providers remained. Even young Nigerians studying law often imagine themselves first as rescuers from police cells, defenders of the oppressed, champions of the masses, not as professionals who bill for commercial work. You still hear children and teenagers say: “I want to be a lawyer so I can help people get out of prison, so I can help people against oppression”, which is, by all means, noble and great, but also shows how deeply the historical imprint is passed from generation to generation.

Because of this generational inheritance, Nigerians subconsciously expect lawyers to charge little or nothing. The earliest generations of Nigerian lawyers were activists, not businesspeople, and that image stuck. Even when you present a client with a fee for a commercial agreement or corporate structure, they instinctively believe: “Ah ah, but is it not just to help me?” The assumption is that lawyers help; they do not earn, and even if they do, then it must be cheap.

Advertisement

The military era reinforced this even more brutally. Under dictatorship, legal work became synonymous with liberation work. Many lawyers took on cases to fight unlawful detention, torture, and rights abuses, again largely free. Society admired them not for financial success but for courage. To this day, the most celebrated lawyers in Nigeria’s historical memory are freedom fighters and activists, not commercial experts. This cultural hero-worship shapes consumer behaviour. Nigerians admire transactional lawyers but do not emotionally respect them in the same way they admired the Gani Fawehinmis and the human rights giants of the profession.

When a society’s first contact with a profession is through activism, professional charity, and political liberation, that society internalises a belief that the profession exists to serve, not to earn. Many professional cultures in Nigeria evolved commercially, including engineering, accounting, medicine, and architecture, but law evolved politically. That early politicisation haunts the profession till today.

This historical foundation is why people still walk into law firms expecting free advice. It’s why someone will call a lawyer at 2 a.m. for police bail and expect it to cost nothing. It’s why Nigerians often see lawyers as moral authorities and activists first, and commercial professionals second. And it’s why even wealthy Nigerians sometimes want to pay peanuts: the cultural memory is stronger than their wallet size.

In essence, Nigeria built an activist legal culture before it built an economic legal culture. That sequence matters immensely. Once a profession is branded as a “public good” from its inception, it struggles to be seen as a “commercial service” decades later.

Advertisement

And that is the foundational and historical root of why Nigerians undervalue legal services even today, not discounting other factors.

But times are changing, so should this generational culture and belief that legal services should be provided for a pittance. Paying for legal expertise is not an expense to be begrudged. The professional practice of Law is an expensive endeavour, a demanding profession that requires years of training, expertise, dedication and specialised skillset. Lawyers are service providers, and law is a form of business too.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.