BY FOLORUNSO FATAI ADISA

One quiet evening in 2009, I was returning from a tutorial class where I taught English and Literature to students preparing for their WAEC exams. Just a few metres from my house, I saw an egbon adugbo perched on a mound of sawdust. We called him Ahua. He was a young private in the Nigerian Army, broad-chested and quick-tempered. He beckoned to me. I walked over. We exchanged jokes and, in that familiar neighbourhood way, he ordered Bolu (thirteen years my junior) to collect the textbooks I held. I did not argue. With soldiers, even friendly ones, you never quite know when banter ends and command begins.

I had barely handed over the books when another egbon, Sobodi, returned to the compound. He and Ahua were friends, roughly the same age. Sobodi had a Barcelona scarf around his neck and a scowl that announced a bad day. Ahua rushed at him, snatched the scarf and tossed out a careless joke. Sobodi demanded it back. Ahua teased that he could burn it. Sobodi’s patience was shattered. He stormed into his single room and reappeared with a machete, his anger now a warning.

Ahua did not flinch. As Sobodi swung the blade, he barked, “You dey bring cutlass for me wey dem use gun train?” What followed was brutal. The soldier overpowered him and landed several blows to his head. Blood pooled. Voices collided. It took the urgent effort of elders like Baba Teacher to calm Ahua and stop the evening from becoming a bigger tragedy.

Advertisement

That night stayed with me. It was more than a neighbourhood brawl. It showed how easily the uniform can turn an ordinary quarrel into violence, how quickly power hardens into intimidation and how long the suspicion between civilians and soldiers has shaped the Nigerian psyche.

That evening was not an isolated drama. It was a small window into a national habit. The uniform did not enter the compound as cloth but as authority. It dictated who could speak, who must retreat and who no longer had the right to be angry. Long before Gaduwa, long before cameras became witnesses, Nigeria had been rehearsing the same script. Civilians brace themselves. Soldiers assert themselves. Both sides carry memories that refuse to heal. Which is why the confrontation between Minister Nyesom Wike and Lieutenant AM Yerima felt familiar. It was not new. It was a fresh chapter of a story the country has never stopped telling.

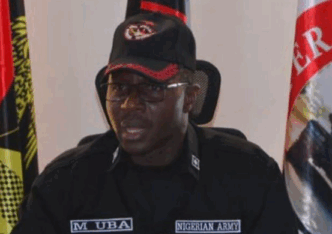

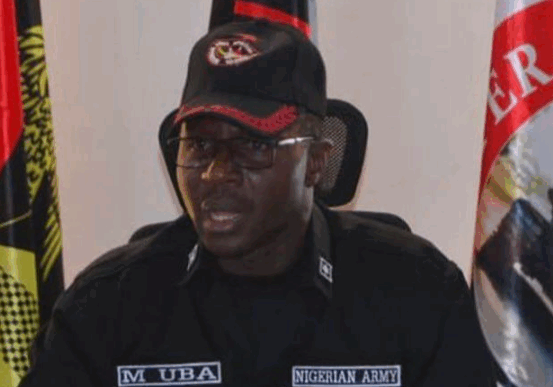

The confrontation between Minister Nyesom Wike and Lieutenant AM Yerima is more than a passing spectacle. It reveals the deeper fractures shaping Nigeria’s civil–military relationship and exposes the fragile culture of authority that colours public interactions across the country. In democracies where institutions hold firm, civilian supremacy is not an abstract idea. It is the foundation of military professionalism. Sections 217 and 218 of the Nigerian Constitution outline the purpose of the armed forces and affirm that military power serves civil authority, not the other way around. Sadly, the clash in Gaduwa offered a different picture and raised urgent questions about how Nigerians understand discipline, power, and responsibility.

Advertisement

Nigeria’s crisis in civil–military relations is both practical and structural. Huntington’s idea of “objective civilian control” demands a politically neutral, professionally insulated military. He writes that the heart of this control is the “recognition of autonomous military professionalism.” The naval officer, reportedly acting as a guard over a parcel of land not designated as military property, reflects the opposite of this professional ideal. It suggests a blurring of lines between institutional duty and private interest, a blurring that has weakened the credibility of uniformed authority over time.

The scene captured in the viral video mirrored this tension. Voices clashed. Tempers rose. Security aides hovered on the brink of confrontation. The minister arrived at the disputed site where construction allegedly continued despite a stop-work order issued by the Federal Capital Territory Administration. The reported presence of uniformed personnel at the location created an unsettling image. A commissioned officer in a role inconsistent with global standards of civil–military relations. In modern democracies, uniforms and private property disputes do not mix.

American sociologist and professor Morris Janowitz gives us another perspective. He envisions a constabulary military—restrained, society-minded, and committed to minimum force. A military that earns legitimacy not by intimidation but by service. If Nigeria embraced this model, the uniform would regain its meaning as a symbol of public duty rather than dominance. The society makes the army. The army does not make the society.

Three lessons stand out. First, the way power is performed in Nigeria. Authority often leans on intimidation rather than procedure. The repeated “Who are you?” and “Do you know who I am?” reveal a culture where status escalates conflict instead of resolving it. These expressions have become the everyday vocabulary of domination.

Advertisement

Second: the restraint displayed by the naval officer. Despite the tense environment, he remained composed and demanded respectful engagement. That steadiness mirrored what scholars call professional discipline, the quiet authority that does not rely on aggression to assert itself.

Third: the conduct of the minister. While legally empowered to inspect the site, his harsh language fell short of the dignity expected of public office. Leadership sets the tone of civic behaviour. When that tone becomes confrontational, it widens the gap between authority and service.

This clash reflects lingering habits from Nigeria’s militarised past. Citizens still expect intimidation from security agencies because history has trained them to. And when civilian leaders employ the same aggressive rhetoric once associated with military rule, the distinction between civilian authority and military behaviour blurs. That blurring is dangerous for any society seeking democratic stability.

The facts of the land dispute require clarity. According to the FCT minister, the land at Gaduwa was first allocated as a public park. The beneficiary company reportedly attempted to convert it to residential use without approval. A section of the land was later sold to former Chief of Naval Staff Vice Admiral Awwal Zubairu Gambo. Construction reportedly continued even after FCTA officials issued a stop-work order. The former CNS’s lawyer insists that all documents are valid. These conflicting claims remain unresolved in public discourse.

Advertisement

What is not in dispute is the minister’s authority under the Land Use Act. The minister of the Federal Capital Territory has the powers to allocate, revoke, approve, and halt construction. These powers apply to all citizens. No law grants serving or retired officers immunity from planning regulations. The principle of equal submission to law is central to democratic governance.

Nonetheless, authority must be exercised with calm clarity. A measured visit would have reinforced institutional order and reduced tension. Instead, heightened emotions turned a regulatory task into a spectacle that exposed gaps in communication and protocol. Nigeria’s broader communication culture magnified this. Citizens approach officials defensively. Officials respond impatiently. Security personnel interpret ordinary behaviour as threat. Political aides escalate rather than calm. Civility becomes fragile; conflict becomes ordinary.

Advertisement

Comparative democracies offer contrast. In the United States and the United Kingdom, military personnel are barred from using their offices for private disputes. Subordinates must refuse unlawful or personal orders. Civilians respect the uniform but understand its limits. Boundaries are clear. Encounters with civilian officials rarely collapse into ego battles because institutional behaviour is predictable.

Nigeria’s struggle is different. Uniforms still carry social power that exceeds legal authority. Citizens still fear soldiers because yesterday’s shadows have not fully lifted. Some former military leaders have also historically interpreted civilian resistance as a security threat, reinforcing old instincts. This cycle of misreading power feeds itself: officials use aggressive rhetoric to demonstrate control; officers respond with defensiveness; citizens withdraw trust.

Advertisement

The Gaduwa clash, therefore, symbolises more than a quarrel between a minister and an officer. It reflects a nation still negotiating the boundaries between authority and service. It shows how quickly an administrative task can become a theatre of ego. It highlights how fragile institutional legitimacy becomes when communication breaks down.

The lesson is simple. A stable democracy depends on restraint. Power must be practised with clarity, not anger. Uniforms must represent service, not dominance. Public officials must lead with composure. Citizens must insist on civility. Only when these principles become habitual will episodes like Gaduwa fade.

Advertisement

On the whole, Nigeria needs stronger institutions and a cultural shift. Authority must be built on discipline. Civility must become a public value. The law must speak louder than personality. The confrontation between Minister Wike and Lieutenant AM Yerima shows how narrow the distance is between order and disorder. It urges Nigeria to rethink how power is imagined and how responsibility is carried. A society cannot thrive on intimidation. It thrives only when power walks with humility and when those who lead recognise that democracy demands dignity in every interaction.

Folorunso Fatai Adisa is a communication strategist and columnist for the Punch Newspaper (Friday Paper). He holds a Master’s degree in Media and Communication from the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, and writes from the United Kingdom. He can be contacted via [email protected]

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.