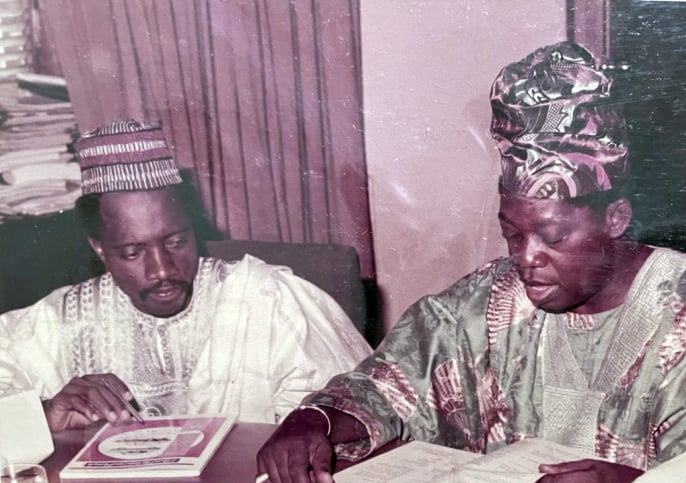

Mohammed, then editor of Concord, with Abiola on a visit to Egypt in 1983

When you have just scooped an interview with a country’s No. 1 citizen and your sales figures have risen astronomically, the last thing you would expect from your employer is a query.

Yakubu Mohammed, Dele Giwa and Ray Ekpu narrowly escaped being fired by MKO Abiola, publisher of Concord newspapers, when they interviewed the new military head of state, Muhammadu Buhari, in 1984.

Mohammed was the senior editor in charge of the daily newspaper, National Concord, while Giwa was the editor of Sunday Concord, and Ekpu was the chairman of the editorial board.

In his memoir, ‘Beyond Expectations’ — an advance copy of which was shared with TheCable — Mohammed said Abiola was a “great human being” who was at times misled by “hangers-on”.

Advertisement

Mohammed wrote: “In January 1984, after the overthrow of President Shehu Shagari’s civilian administration, the new Head of State, General Muhammadu Buhari, at my request, granted an interview to the Concord newspapers. The trio of Dele Giwa, Ray Ekpu and myself conducted the interview, the first major interview with any newspaper by the new military administration.

“Given his frosty relationship with the media when he was Federal Commissioner for Petroleum Resources during which there was an alleged loss of N2.8 billion, General Buhari, still nursing a grievance against the media, issued his famous threat: ‘I shall tamper with the press.’ He said a lot of other things that signalled the policy thrust of the new administration.

“To underline the importance attached to the interview, some of the issues raised with him came on the network news of Radio Nigeria a few hours after the interview as policy pronouncements.

Advertisement

“To all intents and purposes, our own publisher, ironically, was not happy with the scoop scored by his newspapers. Instead of a commendation, he gave the three of us a cold shoulder. Unknown to us, the new military regime had fenced him off and the duo of Buhari and Idiagbon were not relating with him. When we returned from the interview and told the publisher of the warm reception General Buhari gave us, he was rather glum.

“Meanwhile, to find a convenient location to transcribe the recorded interview and do all the segmented stories we had planned to do, we took an IOU of N5,000 (Five Thousand Naira) and stayed overnight in an Ikeja hotel. When we started running the stories from the interview, the circulation figures of the two newspapers hit the stratospherically high figures of 440,000 copies daily for the National Concord and 450,000 copies weekly for the Sunday Concord. That was when an elated publisher proudly proclaimed that his newspapers had the highest circulation in Africa.”

‘PUSHED BY ETHNIC JINGOISTS’

Mohammed attributed the deteriorating relationship with the publisher to the influence of ethnic jingoists.

Advertisement

“The same publisher was pushed by ethnic jingoists to give us a query. The query was preceded by an anonymous letter to the publisher reporting that the three of us were ‘stranger elements’ because we were not Yoruba and we were deemed not loyal to the publisher. The document alleged that we were stealing his money,” he wrote.

“Despite our comfortable accommodation paid for by the company, we took an IOU to go and ‘enjoy’ ourselves in the hotel. And the cheek of it all, we were using our Mercedes Benz cars to the office as if we were doing car racing on the premises instead of doing the work for which we were handsomely paid.

“As if following the management style of the legendary ITT president and chief executive officer, Harold Sydney Geneen, Abiola attached the anonymous letter to the query. Geneen, Abiola’s erstwhile boss in ITT, was reputed to be in the habit of writing an anonymous letter against any ITT executive that he had earmarked for firing and, thereafter, proceed with a query accompanied by the said anonymous letter.

“I replied to the query in only two paragraphs, admitting that we took an IOU of five thousand naira for the three of us, in the course of duty. The money was not stolen. And the outcome of the interview was celebrated even by the publisher himself. Before he got my reply, he had called me to ask about the query and I told him I was typing my reply. He felt relieved that we were individually replying to the query.”

Advertisement

He said the relationship between Abiola and Dele had been frosty for a while and that the publisher’s anger seemed directed at the Sunday editor.

“My understanding was that he was looking for how to get rid of Dele,” he wrote.

Advertisement

“To prevent Dele from replying to the query in a manner that would be deemed offensive, I quickly showed the two of them my reply, which was polite and placatory, and they virtually copied it. All that the chief could do after reading our reply to his query was to apologise to us, acknowledging the fact that we were men of transparent honesty with the highest degree of integrity. The query, he said, was the manifestation of the ill-feeling of those that did not mean well for his company.”

‘ABIOLA ASKED DELE GIWA TO RESIGN OR BE FIRED’

Advertisement

In February 1984, when the dust seemed to have settled, Mohammed travelled to the US on a month-long tour of the country.

“It was in my absence that the crisis between Dele and the publisher came to a head. On March 9, I had called home from my hotel room in New York but could not get through because the phone receiver was misplaced,” he recalled.

Advertisement

“I phoned Dele to send someone to my house to get my family to replace the set. That was when he broke the bad news to me. MKO, he said, had fired him. He gave him up to Monday to resign or should consider himself fired. I advised him not to resign but to allow the publisher to do the difficult job of explaining to the public why he had to fire an editor whose newspaper was doing exceedingly well.

“Come Monday, the publisher, instead of firing Dele, transferred him to the editorial board to work under the leadership of Ray, his bosom friend and his junior in the hierarchy of the Editorial Department.

“I could not get the details of what happened in the office but I kept wondering whether the crisis would have assumed a new dimension if I was around. My intervention had saved some ugly situations in the past. Was the publisher waiting for me to get out of sight? A similar situation arose when the publisher, for no clear professional reason, asked me to transfer Kayode Soyinka, Concord’s London Correspondent, to Lagos soon after he had come home for his wedding. I declined because I couldn’t get the rhyme or the reason for this directive.

“The publisher patiently waited for me to travel out of town to do what he had wanted me to do. He called Duro Onabule, my deputy, to execute Soyinka’s transfer to Lagos, and he, without any question or hesitation, caused a letter to be sent to London asking Kayode to report in Lagos on transfer. Soyinka rejected the transfer and resigned on the spot. Peter Enahoro immediately signed him on as editor of his monthly pan-African magazine, Africa Now.”

‘HOW WE ALL RESIGNED’

Since his appointment as editor of Concord in 1982, Mohammed had been working in the background with an investor on starting a newsmagazine like TIME and Newsweek.

With things going south at Concord in 1984, he said he reactivated the plan, bringing in Giwa, Ekpu and Dan Agbese, who was editor of New Nigerian based in Kaduna.

Minus Giwa, all of them studied mass communication at the University of Lagos in the 1970s.

On his return to Nigeria after a month-long tour of the US in February 1984, he broke the news of the in-the-embryo weekly newsmagazine to Giwa and Ekpu, who had come to his residence to welcome him back and to give him an update on the soured relationship with the publisher.

“Their excitement was both spontaneous and infectious. At this point, I told them that it would be nice to get Dan Agbese on board. Mr Agbese was editing the New Nigerian at the time but we needed no prophet to tell us that sooner than later, the establishment would be through with him. I was asked to invite him for a discussion. Dan did not hesitate to come to Lagos when I invited him. After the New Nigerian, he said, he was hoping to retire into a more relaxed public relations business. But with the picture I had painted, he said he had no choice but to come into the new venture,” Mohammed recounted.

“On the evening of Sunday, July 14, 1984, I drove to Chief Abiola’s residence and dropped my letter of resignation as Editor with his security men at the gate. I knew it was a painful decision. But if I did not take the plunge, we might not have done it. In my letter, I told the publisher to be gracious enough to accept the three months’ notice of my decision to resign. He graciously accepted it with immediate effect.

“I did not even tell my co-conspirators. It was in the afternoon of Monday, the following day, when the publisher called me to say he was coming to the office to give me a small send-off, that I informed Ray and my editorial staff. At this point, Ray quickly wrote his own letter and dropped it in the publisher’s office.

“By the time he came into the premises, he discovered that he was dealing with more than one resignation. He announced at the small ceremony in his office that the three of us—Dele, Ray and myself—had resigned and he had accepted our letters immediately. Newly married Dele was in Ivory Coast with his wife, Funmi, a staff writer with Business Concord, on their honeymoon when the dam broke. He did not resign but his unwritten letter was accepted.”

The four of them went on to found Newswatch in 1984, with the first edition in January 1985. It became arguably the most successful and most respected weekly newsmagazine in Nigeria’s history.

‘ABIOLA WAS A GREAT HUMAN BEING’

In the book, Mohammed eulogised Abiola for his great “human touch”.

“He proved to be a true human being with human feelings, confirming to me that what some people said about him was not mere flattery,” he wrote.

“I was not just a witness to his humility in greatness but in many ways, I was also a beneficiary of that human touch. I had my first child, Usman, in June 1983. At the naming ceremony, Abiola was there with his senior wife, Simbiat. He dominated the scene with his unmistakable presence. He felt at home with my family and guests who took memorable pictures with him. They, too, were witnesses to his humanity and large-heartedness.”

Mohammed also recalled how Abiola allowed him to use his private jet for an assignment.

“Why would a boss ask his staff, for that is what I became from December 1980 when I joined his company, Concord Press Limited, to use his private jet for an assignment I could do just well by public transport or commercial flight?” he asked, rhetorically.

Abiola later ran for president in 1993 and won, but the election was annulled.

He died in detention in July 1998, having been arrested for proclaiming himself president on the first anniversary of the annulment in June 1994.