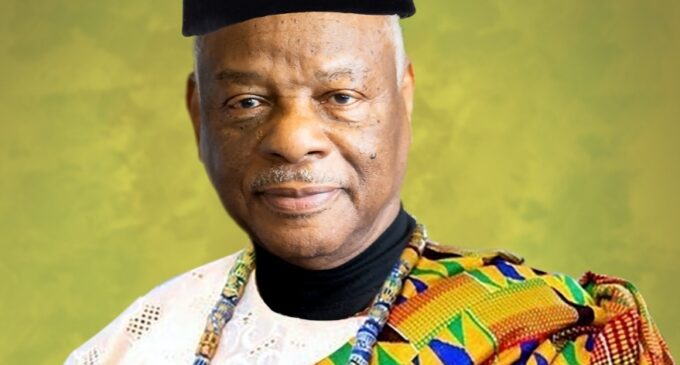

A conversation with Molefi Asante (part one)

Molefi Asante: Breathing Africa, Living Blackness

Em hotep nefer weret!

I have listened to his lectures. I have served on committees with him. I have read his books. I have adopted many of his ideas reworked into Black liberationist thoughts. He has taught me as much as I have taught his works and ideas in classes for over forty years. I have reviewed his books. I have evaluated his manuscripts for publishers. I have gone to Temple University on multiple occasions, the last time to give a lecture on “the construction of words” to his graduate class. I have been asked to endorse the use of his name for two major prizes named after him. When I heard that he wanted to criticize the emerging concept of decoloniality, I did not mind that the venue was in Pretoria, South Africa, far away from my base in Austin, United States. His fans awaited him in Pretoria, and the hall was packed full. The lecture was provocative.

Molefi, the brave Asante

He does not call color red as blue

A brave deity

Who says it as it is

Who does not call a bad thing a good thing.

The knowledgeable one

One that sees everything

He understands the dawn and the sunset

The priest of wisdom.

***

I’ve been to many strange homes,

But none like Nubia, the home of Asante

Where nature is beautifully alive.

I’ve tasted the milk of other lands,

None matches that of mother Africa,

The Black Egypt

Where Molefi was born bright.

***

The great philosopher came;

Saw the future in Africa

He took her and showed her the part of life

Gave her everything needed to forge on;

Blessed is Mother Africa,

With great heritage and culture

Blessed is Molefi,

For keeping the culture, as the name bares.

A super communicator, passion comes with his words, as if the Yemoja, the preeminent goddess of the sea, comes out of the Atlantic Ocean in Bahia to deliver a message from Orunmila, the god of divination. Energy defines his engagement, like Sango, the god of thunder and lightning, issuing majestic commands. Conclusions must be revisited, and Asante turns into that powerful god of the crossroads, Eṣu, whose name must not be called in vain. The past lives in him, the living Pharaoh in the Black World. In another era, Asante would have been transformed into a god and venerated. There are no two people like him. Divide a city into two: one half belongs to Molefi and the other half to Asante!

Conversations around African knowledge productions and the audacity to lay claim to it without being intimidated by the imposing frame of the Western epistemic system would have generally been impossible without the irrevocable commitment of some dedicated persons. Africa was confronted with the demanding tasks of challenging the webs of misconception and the desperate identity assassination that the imperialists dragged them to in the prelude to and aftermath of colonialism. This identity shaming, it must be emphasized, was considered a strategy for which the people would not only be conquered in all dimensions―politically, culturally, socially, economically, and maybe philosophically―but would also be the foundational justification for the subjection of the people to the deprecatory experience they faced during the period of colonization.

Africans were innocent, ignorant of the possible dangers inherent in being conquered by the imperialists, and not prescient enough to foresee what their future would look like with the history of the European expansionism dotting their evolutionary process. The damage was done, and colonial engagements within the 100 years when it held the continent by the jugular shattered, damaged, and trashed all the progress that the Black people had made before the colonizers invaded them. This damage was more debilitating for reasons that are not unconnected to the fact that even when the victims of colonization, Africans, this time around, were dragged to the ground of dishonor, they were practically unaware that the colonially erected institutions left in the wake of colonial imperialism would carry the mark of disrespect, and continue to serve as the agency to sustain the molestation and prostitution of the African image.

After years of anger, the motivation to challenge the age-long calumny overtook a generation of Africans, to which Asante belongs. They began to counter Western fiction with fact, challenge European biases with catharsis, and, more importantly, correct wrong notions with sound knowledge. In the group of African intellectuals who embraced this call to duty is Asante, providing solid and unwavering academic insights that replaced ignorance with knowledge, changing the revisionist information with verifiable information, and substituting jaundiced views with relatively objective perspectives about Africa and Africans.

Asante became an intimidating posture in the academic wave of resistance that is tagged Afrocentrism. The movement began in the mid-21st century as a potent force erected to counter the existing derogation of Africans by the West, eventually becoming an interdisciplinary thing in the long run.

Dubbed as among the most prolific African-American scholars of all time, this intellectual figure has cracked the knot that was considered impossible and made landmark accomplishments in academic waves where his sound contributions enthuse the occupants of the imagined center. There is an infinite possibility, Asante argues, what Africa and Africans represent if they function effectively without hindrance. That many black people do not exude the expected confidence to challenge established biases in the academic, political, or economic systems is a condition facilitated by the colonizers’ watertight efforts to keep them eternally repressed in their deplorable conditions.

It cannot be contested that Africa has contributed meaningfully to the human race and has made impressive landmarks in many areas before the ascension of the European power. Underestimating the continent continues because they have refused to stand up for themselves and make impressive development in areas where they have all been badmouthed. But then there is Asante, who persistently challenges this negative view of black people, from Lagos to New York, not with emotions this time around but with educative works and insight that set straight the records that have been wrongly stated in the first place. We must credit people like Asante for setting the pace and raising the bar and for the effective wave of resistance in all fields.

Molefi Kete Asante has published widely, and his body of works has changed the narratives of the African and black people for good. Central to his academic engagement is promoting African/black interests to repudiate the damaging misconceptions and assassinations of the African image and identity. In his recent publication in 2020, with his scholarly work titled The Afrocentric Pan Africanist Vision, this prolific scholar discusses the vision of the people about what they have in the contemporary time. He argues that the current situation of the people does not in any way represent who they are, and being victims of the history of colonization does not in any way have the possibility of running them aground forever. For Asante, the Pan Africanist vision is shaped by the accumulated experiences that the people have been challenged by in recent or distant times. In other words, the determination to make Africa distinct from the rest of the world is informed by the awareness that they would continue to face predatory temptations by the civilizations that have attained technological and economic transformation if they did not solidify themselves and begin to put in place the needed transformative energies.

It is essential to picture an African future reflective of their true self and capable of accommodating other civilizations without sacrificing their African identity in the process. This means that such a future holds the potential to transform the continent nearly in all conceivable ways. There would be a level of economic self-reliance and technological transformation which would align with their ideological and philosophical principles without necessarily taking away their political beliefs, freedom, and identity. This vision means that the continent would be expediently independent of all the vested interests who have fleeced the continent for ages under different guises. They were considered less technologically advanced, so they were suppressed by the European imperialists and lost nearly all their resources to external civilizations that came to encroach on them for generations. In essence, Asante, in The Afrocentric Pan Africanist Vision, talks about the importance of having this vision and emphasizes more the need to prepare for creating a civilization that can birth and sustain this system. Africa deserves freedom, not only of any political imposition that comes from all civilizations who believe that their economic development should be an automatic ticket for abusing Africa but also of the socioeconomic entanglement they have helplessly found themselves in the recent years.

A very devoted observer of Asante’s academic engagements would notice that not only does he appear to create a breathtaking relationship between his work, but he also makes them appear like an academic work in series. One would be marveled by the close relationship between the work identified above and the one he produced some five years preceding it. In his work, The African Pyramids of Knowledge, this preeminent scholar of inestimable intellectual capacity is unequivocally direct about the fecundity of Africa in knowledge production and value creation. To be candid, there would be no reliable vision for a continent that does not have good intellectual resources on which they can depend for the transformation of themselves and the dislocation of baseless narratives created to keep them under perpetual repression. The knowledge base of the people is used in the management of their society, and this accounts for the enhancement of the identity despite century-long pillaging and deprecatory encounters with the external civilizations. In this work, Asante argues that contrary to the assumption that blacks were devoid of critical thinking and are a strange bedfellow to productive engagement, numerous historical and cultural accomplishments are evident in their greatness even until contemporary time.

Meanwhile, one year before that, in 2014, this same intellectual giant premiered the book titled The History of Africa, which gives sufficient information about the past experiences of Africa and Africans. It is nearly impossible to talk about the African knowledge pyramid without knowing about the people’s history. This indicates that the book written by the sage in 2015 on Africa’s knowledge production and systems is backed by the history, foundation, and past events of the people across all aspects of human endeavor. The History of Africa serves to place in perspective the past experiences and records of the people. For example, the book talks about how the people organized themselves into different political groups using systems that favored and worked for them in the political domain. The decision to organize a political strategy is informed by the knowledge that they demanded very organized structures to enhance their collective progress. If they did not have a robust template for the political system across the continent, the possibility of arranging themselves would not only be slim; it would also be very hard. Asante’s book explains this aspect of human history that they lived before the ascension of Europeans, Arabs, and even during their post-settlement in the continent.

More than it addressed their political past, the book, The History of Africa, also concentrates on the African cultural and religious systems. There seem to be unending ill-conceived generalizations that many civilizations have made concerning Africans, including but not limited to the assumption that the African people were not intellectually evolved to build cultural traditions that are vibrant enough for contemporary times. It would have come as a surprise for people who do not understand the deep-seated connections between colonialism and these narratives. Still, people who understand the underlying Eurocentric agenda from such a position know that it was an attempt to rubbish the continent and justify the corresponding political overtake they later introduced. As much as we understand that such a position lacks a strong background, there would be no way of challenging the impression if individuals do not make necessary and befitting efforts to counter these positions. However, there is no need to panic because people like Asante continue to fumigate the lies against Africans for centuries with facts and figures about their past that can be confirmed by research and replicable scholarship. Essentially, The History of Africa addresses nearly all the aspects of the life of the people and how they did evolve as other peoples of the world did in their various cultural and political experiences.

Asante’s academic contributions do not exclusively center on Afrocentrism. He also has many works that address thematically different yet intellectually complementing themes. For one, this scholar has written essentially on race issues and discussed how the concept had generated more than necessary controversies in the academic world. His writings on race have developed to an edition-by-edition engagement where the idea of racism is looked at from different angles, all of which add to the contemporary understanding of the politics and motivations behind the division of the world along racial lines.

Titled Erasing Racism: The Social Survival of American Nation, the 2009 edition addresses racism and how it has polarized the American society beyond imagination and repair. The American society, it seems, is founded on a philosophy of othering where those who do not come from America or do not express their ideological beliefs are considered less critical, if not less human. To the extent that the society has institutionalized a master-subordinate relationship among their people, they have continued to place themselves beyond others, even unconsciously. Therefore, the book states the different dimensions that racism has taken in American society and how the oppressed groups have made substantial efforts to adapt and protect themselves in the process.

The book, which comes as a recommendation to the international community, instigates more questions than it appears to answer. Asante argues that the African-Americans are overwhelmed and are gradually losing themselves to the carnage of racism. Their identity, cultural traditions, history, and social system are victims of persistent verbal abuse, so much that they do not understand how and where they can begin to challenge the racist prejudices that have faced them from time immemorial. That is the level at which they have degenerated in recent history. Eradicating racism begins with accepting that society has been lopsidedly arranged across racial lines from a distant time. This would put people in the right frame of mind to understand how the white race, the privileged ones in the American society, have enjoyed series of benefits, advantages, and privileges to the detriment of some other people in the society, specifically and the world generally. In this awareness and acceptance, they would begin to correct the age-long anomaly consciously. Without following this systematic path, it would be difficult to talk about putting an end to racism, which has overtaken American society.

In 1971, Asante published a book that seemed to clarify the justification of the same theme covered in the above work. Titled How to Talk to People of Other Races, the book brings up the issue of plural identities and cultural diversities that exist in human engagements. There is the general impression that people would be different in their racial and cultural disposition, though this does not mean that they would not have reasons to depend on one another or forge a strong network of alliance. However, this dependence would be determined by people’s communication when dealing with individuals from different cultural backgrounds. Therefore, the language of communicating with individuals of different races must be respectful. In other words, talk, which is personified as the form of exchanges between people of different races, must be such that the integrity of some people is not threatened or their identity molested. How to Talk to People of Other Races shows that the responsibility of submerging racism stands on the agreement to stem its tide by the people who are important as far as the need to forge a common bond is concerned.

Additionally, it would come as no surprise that this man of inestimable intellectual brilliance is duly recognized far and wide in the world for his outstanding contributions to knowledge production. Apart from being awarded professorate honor in different academic environments, namely, Zhejiang University (2007-2010) and the University of South Africa (2009-present), he has also bagged for himself honors that befit the intellectual greatness he represents. The protruding accolade for which he has been associated reflects the assumption that his contributions do not in any way go without making a substantial impact.

For a man who teaches in the United States, there is no doubt that he has registered a lasting place for Africans in Africa and even in the Western world. Asante’s intellectual activities promote rather than demote African image in places where they have suffered grandstanding and monumental shaming. There is no place in the world where the influence of Asante’s work has not spread to. Asante’s works have served as points of reference and motivation for drawing different academic strategies for upholding the African image across different African countries. Evidently, the recognition he has attracted over time is long overdue.

Beyond the activism in academics, Asante has participated in different involvements that have to do with redeeming Africa’s dented image and restoring its identity in all fora. He once served as the coordinator of diaspora intellectuals, Pan African Scientific Council, African Union, all in 2009, where he promoted quality and excellence that skyrocketed the values of the associations. Interestingly, Asante founded an academic institute, the National Afrocentric Institute, in 1989, and its creation became an instant success across the board. All these establishments he created or where he serves as a member witness immediate transformation because he is conscious about their advancement. He is also a driving force paving the way for them through his intellectual productions.

It cannot be emphasized enough how this philosopher has motivated people who decide to retrace their steps to discover their true African identity. Asante has shown pride in the continent of Africa through his academic involvement and in the various sociopolitical groups he belongs. When academics talk about his greatness, they do not over bloat his importance; when they mention his contributions, they merely state the values he represents. Asante has already won for himself a beautiful place in the knowledge production about the African people. He has expanded the African-American academic engagement magically and retrieved for them the lost image of their ancestors.

Rather than be fazed by the intimidation of others who have considered themselves the general standard for knowledge artistry, Asante has mastered the way to popularize his ideas through the agency of academic engagement. The redefinition of African literature, culture, and history speak for him in decibel that cannot be fully consumed in the annals of history. From political science to historical scholarship, scientific engagements, and professional researches, Asante has roared deeply, and his voice has spread to places one cannot readily predict. He is a dedicated human to the cause and actions he believes in. There has been no time when he backed down from the ideological convictions he is identified with. In the academic industry, he is recognized for the outstanding efforts he makes to advance the collective aspirations and goals of the people.

Asante

The immortal man

Born before our black eyes,

The magical writer,

Touching the marrows of men,

Forever may you live.

No one hears the death of a hoe

You will not die

No one hears the death of cloths

You will stay till the world’s end

No one hears the death of the land

You are covered.

Asante

The man of the people

Who grants rights as privileges

The kind, humble and gentle-hearted

Who sits among the living skeletons

The hero of our people,

May all your wishes be accepted by the gods.

Aṣe!

Please join us for a conversation with an eminent professor and philosopher, Molefi Kete Asante.

Sunday, September 19, 2021

5:00 PM Nigeria

4:00 PM GMT

11:00 AM Austin CST

Register and Watch:

https://www.tfinterviews.com/post/molefi-asante

Join via Zoom:

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/85124202652

Watch on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/tfinterviews/live

Watch on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC2lvX7A2iVndiCq0NfFcb0w/live

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

There are no comments at the moment, do you want to add one?

Write a comment