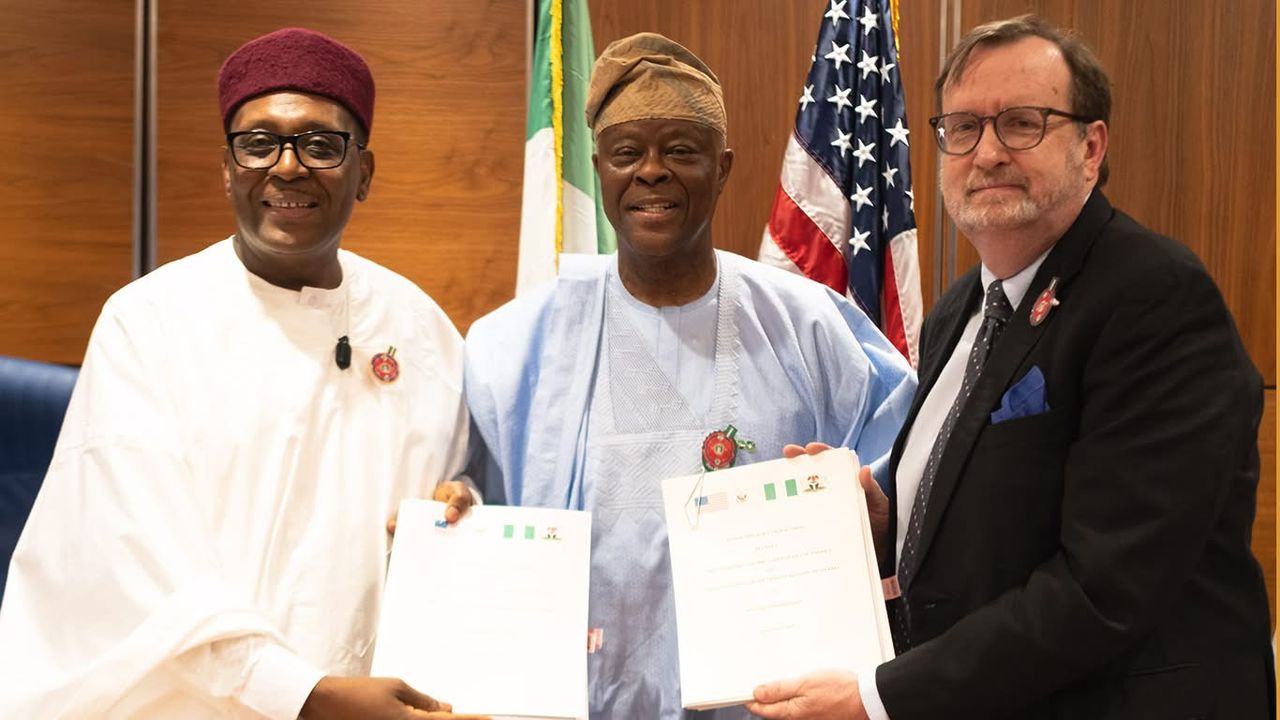

At the signing of the bilateral health agreement between Nigeria and the US

At a time when global attention is fixed on migration, visa restrictions, border controls, and the language of exclusion, Nigeria has concluded a bilateral health agreement with the United States that deserves to be understood on its own terms. Not as a partisan gesture or as a counter-narrative, but as a policy instrument shaped by shared interests and fiscal realities.

The governments of Nigeria and the United States last week, in Abuja, signed a technical Memorandum of Understanding to deepen cooperation in health security, expand access to primary healthcare, and strengthen the resilience of Nigeria’s health system over the period from April 2026 to December 2030. This is by no means a political communiqué. Its importance lies in what it commits both countries to do, and in how those commitments are structured.

Under the agreement, the United States government is expected to provide over two billion dollars (specifically US$2.1 billion) in grant financing to support Nigeria’s health priorities over five years. Nigeria, for its part, has committed to allocating at least 6 per cent of its executed annual federal and state budgets to health, a decision projected to mobilise US$3 billion in domestic financing over the same period. That commitment has already been reflected in the Federal Government’s proposed 2026 Appropriation, signalling that the agreement is being integrated into fiscal planning, with the forthrightness and seriousness it deserves.

The balance is deliberate. External support is defined and time bound. Domestic financing is explicit, quantified, and unavoidable. This design moves away from the habits of indefinite grant reliance toward national responsibility backed by real budgetary choices. In comparative terms, US officials have described the arrangement as the largest co-investment secured by any partner country under Washington’s current global health framework; a distinction that reflects structure, rather than mere generosity.

Advertisement

This matters because global health cooperation is under strain. Donor budgets are tightening. Public patience with open-ended assistance is thinning. At the same time, health threats have become more complex, more mobile, and more expensive to manage. In that environment, agreements that do not clearly price domestic responsibility risk losing both political support and operational relevance.

The scope of cooperation reflects this realism. The agreement prioritises early detection and control of infectious diseases such as HIV and tuberculosis, strengthened disease surveillance and outbreak response, improved laboratory infrastructure and biosafety procedures, more reliable data systems, support for frontline health workers, and access to essential health commodities. These are not abstract reforms. They determine whether a primary health centre can diagnose and report in time, whether an outbreak is contained locally or escalates nationally, and whether routine services endure periods of shock.

Part of the US support is directed toward faith-based healthcare networks, including more than 900 Christian facilities providing integrated HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, and maternal and child health services. While these facilities account for roughly one-tenth of providers nationwide, they serve more than 30 per cent of Nigeria’s population, often in underserved areas where public infrastructure is thin. In a country that carries close to 30 per cent of the global malaria burden and continues to face high maternal and child mortality, this reflects a practical recognition of where care is actually delivered.

Advertisement

For Nigeria, the Memorandum does not introduce a new reform narrative. It reinforces one already in motion. The agreement aligns with the Nigeria Health Sector Renewal Investment Initiative (NHSRII), launched in 2023 and implemented through a Sector-Wide Approach that brings federal, state, and local governments together with development partners, civil society, and the private sector under a single planning, budgeting, and accountability framework. It also builds on the Health Sector Renewal Compact signed in December 2023 under the leadership of President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, which committed all 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory to a unified reform agenda.

This alignment matters. One of the persistent weaknesses of health sector assistance in low- and middle-income countries has been fragmentation, parallel systems, and projects that bypass national planning processes. By tying external support to an existing reform architecture, the Memorandum increases the likelihood that resources will reinforce, rather than distort, system priorities.

For the United States, the agreement reflects a strategic choice to remain engaged where engagement produces durable outcomes. This approach aligns with the United States’ America First Global Health Strategy, which frames international health engagement around national interest, measurable outcomes, and explicit partner-country co-investment, rather than open-ended assistance. Strengthening Nigeria’s capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to health threats is not an act of generosity. It is a calculation rooted in global health security, regional stability, and the recognition that weak systems elsewhere eventually surface as shared risk.

The agreement also signals a recalibration in how partnership is defined. Bilateral health arrangements that combine grant financing with explicit domestic co-financing at this scale are increasingly uncommon. By insisting on measurable national investment alongside external support, the United States is aligning assistance with fiscal responsibility and long-term sustainability, rather than substitution.

Advertisement

There is also an institutional dimension that warrants attention. This agreement was not shaped through public argument or rhetorical positioning. It was negotiated within a technical framework, tied to ongoing reforms, and integrated into Nigeria’s budget and planning processes. That discipline matters because it anchors cooperation in systems rather than personalities, and in processes rather than performance.

The Coordinating Minister of Health and Social Welfare, Professor Muhammad Ali Pate brings extensive experience and tested depth to overseeing reforms that privilege execution over display and systems over symbolism. The Memorandum reflects that enduring orientation. Partnership is linked to reform. Financing is linked to accountability. The emphasis is on what can be delivered, measured, and sustained.

Both governments merit credit. Nigeria for placing measurable domestic resources behind its reform commitments at a time of fiscal pressure and competing priorities. The United States for sustaining engagement in a manner that supports transition rather than permanent dependence, and that recognises the limits of grant-based assistance without abandoning partnership.

What follows will matter more than what has been signed. Implementation, coordination across tiers of government, and visible delivery will determine whether this agreement translates into stronger laboratories, more resilient primary care, better protected health workers, and improved outcomes for Nigerians. Execution will test whether the architecture holds under pressure.

Advertisement

As policy instruments go, the Memorandum is a reminder that even in a constrained and unsettled global environment, serious cooperation remains possible. Not through sentiment or feverish narratives, but through shared interest, institutional credibility, and patience.

Moghalu is a lawyer, strategic communications expert, and public policy adviser with over two decades of leadership across government, international organisations, and development institutions. Currently, senior special adviser to Nigeria’s coordinating minister of health and social welfare.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.