Why Trump’s lawsuit is not a personal media dispute, but a confrontation with Britain’s most powerful state-backed soft power institution.

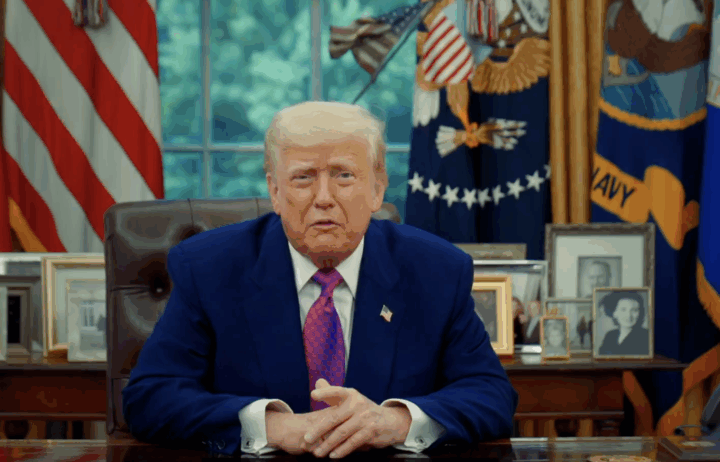

Revelations made by Telegraph of biased editing by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), the public broadcaster, therefore the state media of Britain, of a speech on January 6, 2021 by the 45th and 47th President of the United States of America (USA), Mr. Donald John Trump, should be regarded as a great gift to humanity.

The British Broadcasting Corporation did not emerge accidentally, nor was it conceived as a neutral observer of history. The BBC’s origin showed that it emerged first as a private company, and then it was appropriated by the state and become a statutory corporation. Founded originally in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Limited and formalised under a Royal Charter in December 1926, which took effect and operation on January 1, 1927, the BBC was designed at a time when Britain faced a critical challenge: how to preserve cohesion at home and authority abroad as its empire expanded and later began to fray. Broadcasting was understood early as a strategic tool – one capable of shaping public consciousness more efficiently than armies or administrators.

Under its founding Director-General, John Reith, the BBC adopted the now-famous mission to “inform, educate, and entertain.” Yet embedded within this benign formulation was a deeper philosophy: broadcasting was to serve national purpose. The BBC would cultivate social order domestically and project British values internationally, reinforcing the legitimacy of British institutions and worldview. This was not propaganda in the crude sense, but something more durable – cultural authority masquerading as neutrality.

Advertisement

The launch of the BBC Empire Service in 1932, later renamed the World Service, marked a decisive turn. Broadcasting in dozens of languages across Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, the BBC became a central pillar of Britain’s global presence. During the Second World War, it was explicitly mobilised as a weapon of psychological and informational warfare. In the post-war period, as colonial rule gave way to independence movements, the BBC did not retreat; it adapted. Where direct rule ended, narrative influence began.

By the Cold War, the BBC World Service was firmly entrenched as Britain’s most effective soft-power asset – trusted, respected, and rarely questioned. Its authority derived not merely from professionalism, but from structural positioning: it spoke from Britain, for Britain, while claiming to speak above politics. This paradox – state-funded yet editorially “independent” – allowed the BBC to frame global events in ways that aligned closely with British and broader Western strategic interests, without appearing overtly partisan. Beneath that cocoon, the reality is unravelling.

Today, the BBC reaches hundreds of millions globally – by its own claim, 453 million weekly – often serving as the primary international news source in parts of the Global South. Its language choices, framing decisions, and story selection play a decisive role in determining which governments are seen as legitimate, which societies are depicted as dysfunctional, and which political movements are treated as credible or dangerous. This is power – not through coercion, but through definition. To define reality is to govern perception.

Advertisement

From Trump to the Global South: A Shared Encounter with Narrative Power

It is precisely this power that Donald Trump has now collided with. While Trump’s wealth, platform, and political influence distinguish him from leaders and societies in Africa, Asia, or Latin America, the underlying experience is strikingly familiar: being framed by a Western public broadcaster not as a political actor with agency, but as a problem to be explained, contained, or delegitimised. For decades, nations of the Global South have lived with the consequences of such framing – reduced to caricatures of corruption, instability, or failure, often stripped of historical context and structural causation.

Unfortunately, such framing stuck for two reasons: brainwashing by the same BBC over decades, and failed governance structures in many countries made such states’ publics to often perceive the BBC and its reportage as not merely more legitimate as a news source compared to their indigenous ones, but a welcoming authority capable of questioning their governments. Beneath this, the BBC’s narrative framing waxed stronger.

Trump’s lawsuit, therefore, resonates beyond the individual. It exposes a system in which narrative authority is asymmetrically distributed, where Western institutions claim universality while reserving judgement for others. What differs now is not the method, but the target. For once, the subject of narrative power is not a postcolonial state or a distant leader – it is the 45th and now 47th president of the United States. And that shift alone forces an uncomfortable question into the open: if this is how the BBC exercises power against the strong, what has it meant for the weak? How has the BBC flexed such muscle over the weak since 1921 when it emerged as Britain’s public broadcaster, international image maker, cultural exports machine and narrative influencer?

Advertisement

Patterns, Not Accidents: BBC Narrative Framing in Africa and the Global South

Criticism of the BBC’s international reporting is often dismissed as anecdotal or politically motivated. Yet when examined across regions and decades, a consistent pattern emerges – not of fabrication, but of selective framing. Bias, in this context, rarely takes the form of outright falsehood. Instead, it manifests through language choice, thematic emphasis, omission of context, and the persistent recycling of familiar storylines that shape how entire societies are perceived, understood and regarded.

Africa: Complexity Reduced to Crisis

Across much of Africa, BBC coverage has frequently gravitated toward a narrow set of narratives: corruption, instability, ethnic conflict, governance failure. These issues are real, but the problem lies in proportionality and context.

Advertisement

In countries like Nigeria, for example, BBC reporting has often foregrounded corruption scandals, terrorism, and electoral tensions while giving comparatively limited attention to institutional reforms, economic diversification efforts, or regional leadership initiatives. Structural legacies – colonial extraction, externally imposed economic models, and uneven global trade relations – are often treated as background noise rather than central explanatory factors. The result is a recurring portrait of dysfunction divorced from history.

In Zimbabwe, the long-standing focus on Robert Mugabe’s authoritarianism – while justified in many respects – was frequently presented by BBC (and other Western media) with minimal engagement with the impact of international sanctions, land reform legacies rooted in colonial dispossession, or regional geopolitical dynamics. Leadership became the story BBC focused on and spread globally; structure disappeared.

Advertisement

In Libya, the BBC, like much Western media, devoted extensive coverage to the moral urgency of intervention in 2011, but far less sustained scrutiny to the aftermath: state collapse, militia rule, and regional destabilisation. Nor any serious focus on the motivation for the invasion justified on the guise of a search for weapons of mass destruction (WMD), which never existed, by the American government. The framing of invasion – framed as intervention – as a humanitarian necessity remained largely intact, even as outcomes contradicted the narrative.

These are not isolated editorial decisions. They reflect a broader tendency to simplify complex postcolonial realities into morally legible stories for Western audiences. Give a dog a bad name!

Advertisement

The Middle East and Beyond: Language as Judgment

Nowhere is narrative framing more visible than in the Middle East. Terms such as “militant,” “hardliner,” “regime,” or “strongman” are applied particularly by the BBC unevenly, often depending on a government’s alignment with Western strategic interests. Civilian casualties are described with differing levels of emotional detail depending on who inflicts them. Context is compressed; immediacy dominates. That has been the BBC’s pattern all too familiar to be mistaken.

Advertisement

In coverage of Palestine, critics have long noted disproportionateness in language – how agency is assigned, how violence is contextualised, and how power imbalances are neutralised through vocabulary that implies equivalence where none exists. In BBC’s reporting on Iran, internal dissent is foregrounded while the effects of prolonged sanctions on civilian life receive comparatively limited sustained attention.

In China–Africa relations, BBC narratives frequently default to “debt-trap diplomacy” framing, often without equivalent scrutiny of Western lending practices or historical debt structures imposed by Bretton Woods institutions. The complexity of African agency – why governments choose certain partners – is flattened into suspicion-driven narratives.

How Narrative Framing Works: The Architecture of Bias

Understanding BBC influence requires understanding how framing operates:

- Language: Descriptors such as “controversial,” “populist,” or “authoritarian” are not neutral; they precondition interpretation and influence perception.

- Selection: What stories are covered repeatedly – and which are ignored – determines perceived importance. The real purport of agenda-setting in media.

- Sequencing: Leading with violence or scandal before context primes audience judgement.

- Expert Curation: Whose voices are deemed authoritative – often Western analysts over indigenous scholars – shapes legitimacy.

- Moral Positioning: The BBC frequently occupies the role of implicit moral arbiter, guiding audiences toward “reasonable” conclusions.

None of this requires fabrication. It requires editorial power exercised consistently over time.

Donald Trump: When the Frame Turns Inward

It is against this backdrop that BBC coverage of Donald Trump becomes instructive. Trump was not merely reported on; he was framed – as aberration, threat, and deviation from acceptable (Western) political norms. Clips were selected to emphasise incoherence, aggression, or extremity. Policies were often interpreted primarily through reaction rather than intent. His supporters were frequently characterised as grievances rather than constituencies.

The alleged biased editing of Trump’s 2021 speech, now the subject of legal action, fits neatly within this established pattern. The issue is not whether Trump made controversial statements – he did, as that is his persona and personality – but whether editorial decisions systematically reinforced a predetermined narrative at the expense of balance and context. When a publicly owned and funded international broadcaster, which the BBC is, edits a political figure’s speech in ways that amplify a particular interpretation, it moves from reporting into narrative construction.

For leaders in the Global South, this experience is familiar. What makes Trump’s case unusual is not the method, but the visibility of the subject. Trump’s wealth and platform as president of the US allow – and embolden – him to contest the framing openly. Most nations and leaders do not have that luxury – or the liver. Indeed, most leaders would, given the overbearing influence of the BBC, viewed the questionable reporting or editing as emanating from a voice of inviolability representing a sacred shrine of colonial sepulchre; and, they will merely lick their wounds in secret and silence.

From Pattern to Principle

Taken together, these examples suggest that the BBC operates less as a neutral mirror of global reality and more as a curator of acceptable narratives, shaped by institutional history, cultural assumptions, and geopolitical alignment. This does not require conspiracy, only consistency. Over time, such framing accumulates power – defining legitimacy, shaping reputations, and influencing policy outcomes far beyond Britain’s borders.

Trump’s lawsuit, therefore, is not an anomaly. It is a rare moment when the mechanics of Western narrative authority are made visible. And once exposed and starkly visible, they invite scrutiny – not only from Trump, but from every society that has ever found itself explained, judged, reduced and simplified by a voice claiming to speak for the world while projecting neo-colonialist irredentism.

Why This Is ‘Britain vs Trump’ – Not ‘BBC vs Trump’

To describe Donald Trump’s lawsuit as a dispute with the BBC alone is to misunderstand the nature of the institution involved. The BBC does not operate as an ordinary media organisation. It is not a privately owned outlet accountable only to shareholders or advertisers. It is a public broadcaster established by Royal Charter, funded through compulsory licence fees, and renewed with parliamentary approval. In practical and symbolic terms, the BBC is an extension of the British state’s public authority. The BBC is Britain’s global and therefore hegemonic informational war machine, which has been in active service since January 1, 1927, cunningly and deceptively presented to the world as a media house for public good. Trump, given his insights in media operations, knows this. His political trajectory further made the spectacle more telling such that he appears bent on scoring a geopolitical victory – not over BBC, but over the owner of the BBC, the empire, Britain, historically the colonial overlord of America.

This distinction matters profoundly. When a private media company edits content in a biased or misleading manner, the offence is journalistic. When a state-backed international broadcaster does so, the implications are political. The ‘editor’ in the latter instance is not the editorial board of the media house; it is the ownership – the state – asserting its influence. The line between editorial judgement and institutional power becomes blurred, especially when that broadcaster enjoys unparalleled global reach and credibility which has been the story of the BBC for 98 years now, two years shy of a whole century.

The BBC’s claim of editorial independence, while formally seemingly accurate, does not negate its structural reality. Independence exists within a framework defined by British law, British political culture, and British strategic interests, domestic and external – but more external. The BBC’s leadership is appointed through processes shaped by British government policy; its charter renewal depends on state approval; its World Service funding has, at critical moments, been supplemented directly by the UK government to advance foreign policy priorities. These are not accusations; they are documented institutional facts.

The BBC was not originally founded or established by the British government. The BBC was registered by a group of radio wireless telegraphy companies led by Italian physicist Guglielmo Marconi’s firm, as British Broadcasting Company Limited on October 18, 1922. Noticing its influence on the people, then British monarch, George V, issued a Royal Charter on December 20, 1926 usurping the company and ordering that when its licence expired on 31 December 1926, it would not be renewed, but the company would become a statutory corporation from January 1, 1927 to serve British interests domestically and globally. He also became the first British monarch to broadcast to the citizens live from the radio house during World War I. For Nigerians, does this hint about the emergence of BBC bear any resemblance to the founding of the Nigerian Television Authority (NTA)?

In this context, therefore, the alleged biased editing of Trump’s speech cannot be dismissed as a newsroom lapse. It must be understood as an action carried out by an institution that represents Britain to the world. The reputational damage inflicted on Trump – if proven – was not delivered by a rogue editor, but by a globally trusted state-linked broadcaster whose credibility rests on its association with British governance, monarchy, empire, professionalism, and moral authority. The BBC was doing state service when it reported on the now contentious Trump case; the BBC is always on state service duty when it broadcasts globally. In the context of state media as a tool of international diplomacy, under which the BBC operates, the media is the state, and the state the media.

This is where the dispute transcends Trump’s personality. Trump is not suing a journalist; he is confronting a narrative system that has historically positioned itself as arbiter of democratic legitimacy. His presidency at the time – as it appears to be even in his second coming – directly challenged pillars of the post-war Western order – multilateralism, NATO orthodoxy, liberal internationalism, and the moral supremacy of Western institutions. It is therefore unsurprising that he became an object of sustained institutional hostility across Western media ecosystems, including the BBC. Actually, the BBC led the charge.

Seen through this lens, the lawsuit reflects a deeper contest over who gets to define truth, normalcy, and legitimacy in global politics. When the BBC frames a leader as reckless, dangerous, or unfit, it does so with the accumulated authority of Britain’s historical prestige, imperial legacy, official stamp, and cultural capital. That framing travels faster and farther than any rebuttal. That framing sinks deeper into the fabric of the international political system workings than medication directly injected into the veins of a sick person.

For decades, this power asymmetry has been experienced primarily by states and leaders in the Global South. Their grievances were often dismissed as sensitivity or authoritarian intolerance of free press. What makes the Trump case different is not the nature of the treatment, but the identity of the subject. A former U.S. president, now a sitting U.S. president – wealthy, influential, and institutionally embedded – has chosen to contest the narrative power of a British public institution. Trump is questioning Britain, not the BBC. It is the rewriting of geopolitical influence.

In doing so, Trump inadvertently exposes a question Britain has rarely had to answer: what happens when a state-backed broadcaster’s narrative authority is challenged as a form of political power rather than journalism? If the BBC is merely media, then accountability should be limited. But if it is – as history and structure suggest – a pillar of British soft power, of British international information war machine, of British international diplomacy for cultural and political projection, then its actions carry state-level consequences.

This is why the case cannot be reduced to damages or defamation. It is about institutional responsibility in an age where information has claimed its place as power beyond any other known international affairs instruments of influence, and where public broadcasters shape global political outcomes as surely as diplomats and sanctions. When narrative authority becomes a tool of geopolitical influence, it must also become subject to geopolitical scrutiny.

In that sense, Trump is not just confronting the BBC. He is confronting Britain’s most effective and least accountable export: its ability to define reality while claiming neutrality.

This is why the sum of $10 million which Trump is demanding appears not only small, even infinitesimal, but insignificant. Trump must demand a sum above $10 trillion; because, Trump’s victory over the BBC, nay over Britain, in this case, will be the victory of reason over state-sponsored narrative framing dressed as media. Britain since it emerged as an empire, has done incalculable damage all over the world; and the BBC has been its instrument or brainwashing, narrative creation, framing, and perception influence. And, calculating the damage Britain has inflicted on persons, institutions, and states – particularly those in Africa and the Global South – even if vicariously, from the Trump victory on this matter, if put in monetary value, could go over $100 trillion.

Trump may not need the money; when he wins the case, he can afford to donate all or much of the $10 trillion to all those nations whose reputation, leaders, international image and political systems the BBC – yes, Britain – has damaged over the decades.

Why $10 Trillion? The Price of Narrative Power

The call for Donald Trump to demand $10 trillion from the BBC is not a literal legal calculation; it is a symbolic intervention. It is a deliberate attempt to expose the vast asymmetry between the scale of narrative power exercised by Western state-backed media and the minimal accountability mechanisms available when that power is abused.

Ten million dollars addresses an edited speech. Ten trillion dollars may gesture toward something far larger: the cumulative damage of decades of narrative authority deployed without consequence. The BBC’s influence is not confined to elections or personalities. It shapes investor confidence, foreign policy assumptions, aid flows, diplomatic legitimacy, and even internal self-perception within nations. When such power is exercised systematically – under the cover of neutrality, as the BBC often does – the costs are distributed across societies, not balance sheets.

For Africa and the broader Global South, this symbolic figure resonates deeply. For decades, countries have borne the consequences of narratives they did not author and could not contest on equal footing. Nations have been branded “failed,” “fragile,” or “corrupt” in ways that hardened external perceptions and narrowed policy options. Conflicts have been simplified, leaders caricatured, histories truncated, and agency diminished, all through language that appeared objective but functioned politically.

What $10 trillion represents, therefore, is not compensation, but reckoning. It asks a question Western media institutions have long avoided: what is the accumulated cost of defining the world for others? If sanctions have economic prices, and wars have human costs, then narrative warfare – subtle, sustained, and global – must also carry consequences.

Trump’s lawsuit, provocative as it is, opens a door that smaller nations have never been able to force open. It reframes media bias not as hurt feelings or reputational inconvenience, but as a form of structural power with material effects. And once framed this way, the demand for accountability ceases to sound outrageous.

Conclusion: When Neutrality Becomes Power

The dispute between Donald Trump and the BBC is not ultimately about Trump. Nor is it even about Britain alone. It is about an international order in which a small number of Western institutions retain extraordinary authority to define truth, legitimacy, and normalcy, while remaining largely insulated from challenge. The BBC’s greatest strength has always been its credibility. Yet credibility without accountability is not neutrality; it is power. When a public broadcaster, backed by state authority and global trust, shapes political reality through framing rather than fabrication, it exercises influence that as such rivals diplomacy itself.

For Africa, Asia, and Latin America, Trump’s confrontation with the BBC is instructive. It reveals that the narratives shaping global hierarchies are neither natural nor incontestable. They are produced, curated, and defended by institutions with histories, interests, and blind spots. Whether Trump wins or loses his lawsuit is almost beside the point. What matters is that a crack has appeared in the façade of unquestioned Western media authority. And once that façade cracks, it invites a broader demand – from nations long spoken about rather than listened to – for a world in which narrative power is finally subject to scrutiny.

If the BBC wishes to remain ‘the world’s most trusted broadcaster,’ it must accept that trust now comes with a price: accountability equal to influence. And if that price sounds excessive, it is only because the cost of silence has been borne by others for far too long.

Abang, PhD, foreign policy and public diplomacy specialist, eminent communication expert and consummate public relations professional, wrote in from Abuja, via [email protected]

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.