PWDs | File photo

A recent incident at the Murtala Muhammed International Airport (MMIA) in Lagos has cast a spotlight on the glaring gap between Nigeria’s disability rights legislation and the reality faced by persons with disabilities (PWDs) on a daily basis.

On March 27, Debola Daniel, son of Gbenga Daniel, former governor of Ogun state, recounted how he and his family were denied entry to a Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) outlet at the airport because of his wheelchair.

According to Debola, despite efforts to rectify the situation, the manager insisted that wheelchair users of all shapes and sizes were not permitted in the premises and asked the group to leave immediately.

“Today I felt less than human, like a guard dog not allowed into the house. Lonely and isolated,” he tweeted.

Advertisement

“To be a disabled in Nigeria is to be undesirable, unwelcome and unaccepted. As I’ve said before, it’s a lonely, scary and isolated place.”

Less than 48 hours after the outcry, the Federal Airports Authority of Nigeria (FAAN) shut down the fast food outlet.

Obiageli Orah, director, public affairs and consumer protection at FAAN, said the authority made its decision after investigating the matter.

Advertisement

“In line with Lagos State law on people with special needs, Part C, section 55 of General Provisions n Discrimination which states that, ‘A person shall not deprive another person of access to any place, vehicle or facility that members of the public are entitled to enter or use on the basis of the disability of that person’,” FAAN said.

Orah said the agency instructed the KFC management to tender an unreserved apology, in writing, to the affected passenger with restricted mobility (PRM) and a policy statement of non-discrimination be written and pasted conspicuously at the door post of their facility at MMIA before it resumes operation.

WHAT DOES THE LAW SAY AND WHAT IS THE REALITY?

Advertisement

According to Nigeria’s Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act, a person with disability shall not be discriminated against on the ground of his disability by any person or institution in any manner or circumstance.

The law also mandates that a person with disability has the right to access the physical environment and buildings on an equal basis with others.

“A public building shall be constructed with the necessary accessibility aids such as lifts (where necessary), ramps and any other facility that shall make them accessible to and usable by persons with disabilities,” the act reads.

However, none of these have been the reality for differently-abled persons in the country.

Advertisement

As a realtor living with cerebral palsy, Olawale Dada is certain architectural discrimination against PWDs is widespread in Nigeria because real estate developers are only focused on profit.

“As an adult with cerebral palsy and a realtor, I have come to realise that most real estate developers in Nigeria build with measurements that only help them make more money from limited space,” Dada told TheCable.

Advertisement

“Hence, accessible building which is a global standard is not considered in most properties in Nigeria, leaving wheelchair users like myself to be faced with the challenge of navigation to achieve mobility.

“In most cases, it results in damage to my wheelchair and physical injury in my attempts to navigate through the limited space.”

Advertisement

Although some buildings include ramps for wheelchair users, Dada said some do not bother to ensure the structures are built to standard measurements to easily aid usage.

“I could not visit my wife in the hospital when she gave birth because of this. If I had dared to use the hospital ramp, it would have been a free fall which could have led to serious injuries like spinal cord injury, injury to the head or even lead to death if the speed of fall is much,” he said.

Advertisement

Data on disability inclusion — a component that is critical in influencing planning and budgeting — in Nigeria is sparse as the group is among the most excluded.

Citing a World Health Organisation (WHO) report in December, James Lalu, executive secretary of the National Commission for Persons With Disabilities (NCPWD), said there are 35.1 million persons currently living with disabilities in the country.

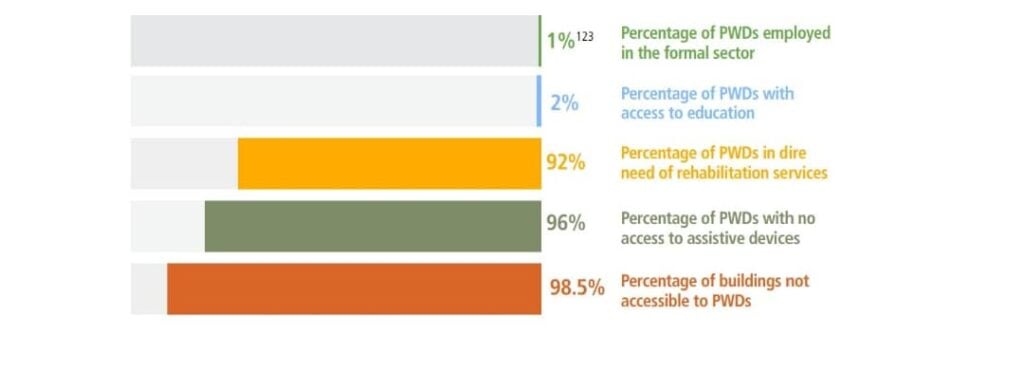

For this fraction of the population, getting into 98.5 percent of public buildings is near impossible, according to a 2022 Agora policy report.

In addition, the report states that one percent of PWDs are employed in the formal sector, two percent have access to education, 92 percent are in dire need of rehabilitation services, 96 percent have no access to assistive devices.

None of these conform to Nigeria’s disability law.

IMPROVING THE LIVING CONDITION OF PWDs IN NIGERIA

Asides imposing sanctions like fines and prison sentences on those who contravene it, the law also stipulates a five-year transitional period for modifying public buildings, structures, and automobiles to make them accessible and usable for people with disabilities.

But, so far, the outcome has been far from expected and most parts of the law have not even been implemented in many states. As of 2022, only 19 states had adopted the act.

“We need to start seeing more accessibility options in buildings and communities. How a blind person would adapt to a disaster is not the same way a person on a wheelchair or a deaf person would,” Lalu had told TheCable after Nigeria’s worst flooding in a decade swept PWDs away.

“For instance, a person in a wheelchair can see water coming from afar and scream for help, the deaf person would not hear but the blind person would hear and not be able to run.

“It’s very complicated, but unfortunately, it’s the way things are. Except there is an intentional effort to carry everyone along, then we’re still at the same spot.”

In December, Betta Edu, the suspended minister for humanitarian affairs and poverty alleviation, said public buildings across the nation lacking proper accessibility for PWDs would face closure in 2024.

Lalu re-echoed Edu’s words and said the commission would start taking action as soon as the ultimatum given to organisations by the federal government expires on January 16, 2024.

However, reports of buildings being shut for violating the law and the rights of the millions of differently-abled persons in Nigeria are nearly non-existent — a situation these vulnerable persons fear would do little to alleviate their struggles.