Tinubu and the new service chiefs

“Fellow Nigerians!” That is a phrase that, in its military style and rendition, might not be too weighty in meaning for the generation that came after the last military regime in this country.

But for my own and the older generations, that is a phrase that evokes a melange of fear and anxiety, but also jubilant expressions.

Could Nigerians have heard such a phrase again in the last few weeks had the reported attempt to sink the current administration succeeded?

For the fears and anxieties that it came with, those who witnessed what the raw power of the jackboot era meant, always pray “never again” in the history of our country.

Advertisement

Loss of freedom, human dignity, lack of accountability, abuse of human rights, centralised and authoritarian control, suppression of civil liberties, and the use of force to maintain order are the norms under a military government. It also came with suspension of the constitution, banning of political parties, and ruling by decrees and executive orders. That was an era when military laws were applied to civilians. They had no choice in the matter.

This reminds me of a story told by a friend who was one of the editors picked up after ThisDay newspapers had published a story which the military under the late dictator, Sani Abacha, found offensive. My friend said that after they, about four of them, including their then editor, were all whisked to the Directorate of Military Intelligence in Apapa, Lagos, the then director, a man whose capacity for inflicting the most heinous pains on humans was well documented, took them to some dingy rooms where some unfortunate, incarcerated citizens were languishing. This was after a series of mind-torturing conversations that made each member of the captured editorial team sweat profusely in an air-conditioned room.

Making them see those citizens in their various states of dilapidations was itself a strong statement. But in a very chilling, final statement, as if those gory scenes of languishing souls were not enough, he was reported to have warned the visibly cowed journalists: “If I have reasons to invite you to this place once again, I will waste you and flush you.”

Advertisement

My friend, having no strength for any pretensions, confessed that he instantaneously felt some drops of urine in his underpants after hearing those words. What with the disappearance of government critics, state-sponsored assassinations, arrests and detentions without trials?

Such are the memories that suspension of the constitution bring forth.

But for the jubilant part of it, Nigerians trooped to the streets at the sound of every martial music followed by “Fellow Nigerians” to celebrate the coming of new ‘Messiahs.’

This writer witnessed such street celebrations in 1983, 1985, 1994, and 1998, even when this (1998) was not a coup, but the sudden death of a sitting dictator that some would rather consider to be a palace coup.

Advertisement

Of course, the older generation of Nigerians witnessed military interventions of the 60s and the 70s.

There were coups that were successful. In such cases, the coupists reaped bountifully from their daring ‘investments.’ And there were coups that failed when the culprits paid dearly for their ambitions.

1983 was the year that the late General Muhammadu Buhari staged a coup to oust the undoubtedly corrupt Shehu Shagari administration. It is significant to note that apart from the worsening living conditions of Nigerians at the time, the second term election supervised by the defunct National Party of Nigeria (NPN) government, believed to be largely flawed with abuse of state power to perpetuate the NPN in power, was a major catalyst for that intervention. With the mayhem that followed the blatant electoral frauds of the Second Republic, coupled with the economic hardships, a good ground had been prepared for the military to return and for them to be warmly welcomed by the people.

Quite expectedly, when the Buhari-led team struck on December 31, 1983, the streets went jubilant with the expectations that new ‘saviours’ had come.

Advertisement

On August 27, 1985, after less than two years, when Nigerians had come to the conclusion that the Buhari regime, with its high-handedness, was not the Messiah they needed, Ibrahim Babangida struck, again, sending jubilant Nigerians to the streets.

Till it was the turn of General Sani Abacha after the palace coup that ousted Chief Ernest Shonekan, Babangida’s Interim National Government leader, Nigerians were used to “Fellow Nigerians” at every stage until the return to democratic rule on May 29, 1999.

Advertisement

All those were also preceded by instances, including the January 15, 1966 coup led by Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu, that marked the first military intervention in Nigeria’s politics after independence.

There was also the July 29, 1966 coup led by Lt. Colonel Yakubu Gowon, who equally addressed “Fellow Nigerians” after the counter-coup that overthrew General Aguiyi-Ironsi.

Advertisement

In Nigerian military and political history, the phrase “Fellow Nigerians” holds deep symbolic significance. It is the usual traditional opening words used by military leaders to announce take over of governments by a new set of top military brass. It is also used whenever a military leader wants to address the citizens.

“Fellow Nigerian” carried with it that typically formal, grave, and authoritative seriousness often associated with military styles of command and orders.

Advertisement

Today, the phrase carries with it a mix of historical weight and irony, evoking memories of Nigeria’s turbulent coup era.

No Nigerian who is a witness to the history of military rule would read of the report of any coup in the offing and not be alert to details, knowing what the implications are.

But then, as in many things Nigerian, no one knows the truth after the Defence Headquarters immediately denied that the October 1 Independence Day parade was yanked off to neutralise an alleged plot by some elements in the military.

But then, there is a thick feeling of “if there is no fire, there will be no smoke” in the Nigerian air.

Even when the Defence Headquarters said that the ongoing investigation involving sixteen of its officers “is a routine internal process aimed at ensuring discipline and professionalism is maintained within the ranks,” adding that “an investigative panel has been duly constituted, and its findings would be made public,” most Nigerians have refused to buy what they think is a “cock and bull” story.

But the wind that is blowing is opening up the anus of the chicken (to put it in local expression).

One day after another, there are more seemingly unassailable facts that the military is indeed after key civilian figures suspected to have had some unholy alliances with some of its men and officers over some yet-to-be-determined reasons. Already, the veiled “former southern governor” has been unveiled to be known as Timipre Sylva. He was the governor of Bayelsa state and was a minister under the Muhammadu Buhari administration. His house in Abuja has reportedly been ransacked. His brother has reportedly been picked up. He, too, has reportedly fled to Senegal, en route to Argentina.

But who wants a coup? The worst of civilian administration, it is often stated, is better than the best of a military regime (even if this is another subject for a debate).

While a coup might not be desirable, the strident lamentations of many Nigerians over the cost of living could also be a reason a section of the populace may feel Nigeria should try something else.

In a country with a tenuous security situation demanding a high level of uniformed men to maintain peace and order, temptations are believed to be very high for top military brass to test their strengths, especially if both the military and the civilian leadership are in an asymmetrical relationship.

But this does not appear to be so under the current Bola Ahmed Tinubu administration. One should assume, and undoubtedly so, that there is, currently, an acceptable level of what is called “civilian control” which subordinates the military to the civilian authorities.

In Nigeria, there is a high level of military operations ongoing in the north-east, north-west, north-central and the south-east. Relatively, the south-south and the south-west still seem to enjoy some stability in spite of some breaches in robberies, kidnapping, and ritual killings that have not really demanded heavy military operations. The military’s task of keeping peace, however, demands professionalism and a total submission to the supremacy of the constitution.

In other words, the armed forces must operate within the ambit of constitutional provisions even when conducting their operations to secure the country for a stable civilian administration.

This is why, at will, the President and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Federal Republic can remove service chiefs.

That was the power Tinubu exercised a few days ago when he shocked the nation with a sweeping removal of all service chiefs but one.

Inevitably, the poser is being raised on the nexus between what the defence headquarters downplayed as “a routine internal process” and the wide net that is now fishing for remote and direct actors in a drama, the denouement of which we may not know for now.

And more importantly, what is the connection between the coup scare and the decision by the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces to effect a change in his team of commanders?

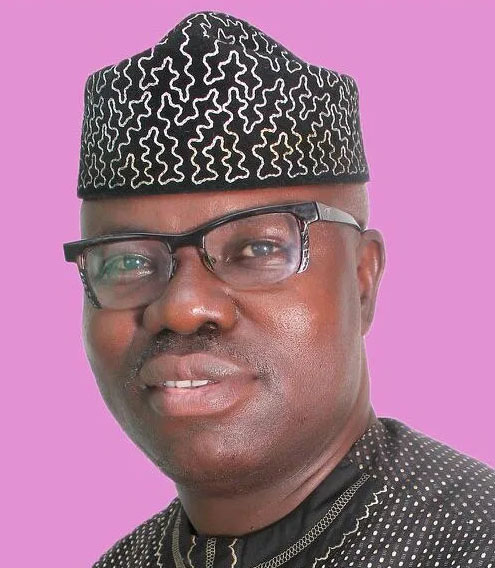

Semiu Okanlawon is CEO, S-OK Advisory and Media Limited, and publisher, NPO Reports

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.