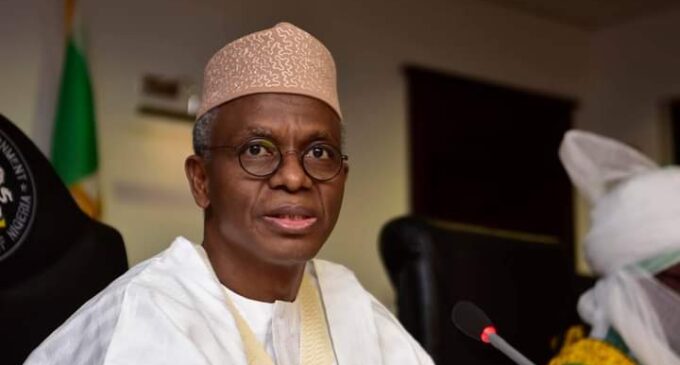

The Economist’s hagiography of el-Rufai

“He banned political meetings and free speech. He detained thousands, used secret tribunals, and executed people for crimes that were not capital offences.”

“His economics, known as Buharism, was destructive. Instead of letting the currency depreciate in the face of a trade deficit, he tried to fix prices and ban ‘unnecessary’ imports.”

“He expelled 700,000 migrants in the delusion that this would create jobs for Nigerians.”

“Should a former dictator with such a record be offered another chance?”

“Few nowadays question his commitment to democracy or expect him to turn autocratic: he has repeatedly stood for election and accepted the outcome when he lost.”

“He would probably do a better job of running the country, and in particular of tackling Boko Haram.”

“As a northerner and Muslim, he will have greater legitimacy among villagers whose help he will need to isolate the insurgents. As a military man, he is more likely to win the respect of a demoralised army.”

“We are relieved not to have a vote in this election. But were we offered one we would—with a heavy heart—choose Mr Buhari”.

The eight quotes above come from different parts of an article about the then-upcoming Nigerian Presidential Election that London-based magazine, The Economist put out six years ago on February 7th, 2015. I am not going to waste your time pointing out just how the actions and outcomes of a Buhari presidency have shown how wide of the mark the postulations in this article were, it should be clear to anyone who has either lived in Nigeria or closely observed the country since then.

What we are going to do instead is use the above article to guide our reaction to a recent piece in The Economist about Kaduna governor, Nasir El-Rufai that triggered some uproar on social media with its portrayal of El-Rufai as a “brave, forward-looking reformer” responsible for economic growth in Kaduna and a decline in inter-ethnic violence in his state.

Kaduna State has a multifaceted security crisis with the Christian-dominated southern section attracting a constant wave of lethal attacks from Fulani militias. A lot of the largely Christian minority has described these attacks as subtly state-sanctioned systematic violence aimed at removing them and taking over their lands.

In February this year, former US ambassador to Nigeria, John Campbell, wrote the following for the Council of Foreign Relations: “Kaduna is increasingly the epicentre of violence in Nigeria, rivalling Borno state, the home turf of Boko Haram. In rural areas, conflicts over water and land use are escalating, and Ansaru, a less prominent Islamist group, is active.”

A July 2020 SBM Intelligence report showed the numbers over the years from 2008 to 2020, making it clear that the violence in the state had clearly increased in both frequency and number of fatalities.

The state government, on the other hand, keeps insisting that these attacks as communal clashes. The state government’s position is not helped when we remember that in October 2018, the paramount ruler of the Adara Chiefdom, Agwom Adara Maiwada Galadima went for a meeting with Governor El-Rufai, and was kidnapped and killed alongside his wife on his way back. This happened amid tensions arising from a proposal by the state governor to convert the chiefdom to an emirate, a proposal that was seen by Christians in the state as deliberately touching on their nerves as they have historically never lived under Emirs, a traditional title open only to Muslims. Of course, the same El-Rufai was to pick a Muslim as his running mate later on, deliberately upsetting the religious balance that had always characterised the leadership of the state.

These facts, and the reactions of actual Nigerians on Twitter, go to show that The Economist’s article was to be taken with a generous helping of salt but then there is a deeper angle to this. Regardless of how angry the reactions by Nigerians on Twitter and offline are, the cold truth is that the article is in The Economist and its reach across print and electronic platforms covers a range of 40 million readers largely drawn from groups with high-income and literacy levels which makes it influence with business leaders and policy-makers across the world.

It is not enough to know and say the right things. Effective communication in statecraft and business demands the right things have to be said in the right way, in the right rooms, and to the right people. Buhari, el-Rufai, and the others are communicating strategically while we invest in impotent bluster.

Representatives of the Eurasia Group have also been involved in pushing certain narratives about Nigeria that align with the leaning of the Buhari Administration. The Eurasia Group was founded by Ian Bremmer who advises leading executives, money managers, diplomats, and heads of state. Ian Bremmer also heads GZERO Media, a company dedicated to providing intelligent and engaging coverage of international affairs.

Clearly, there’s an international campaign being run with foreign journalists and academics involved and this has been going on since before 2015. We can either complain or organise resources and play the game, and we must realise that for every article seen on the pages of these international media channels, several meetings and discussions are going on where lobbying is done and things are being privately said and agreed on in the rooms that matter.

Nagging is not a viable statecraft tool. Nagging only works in personal relationships with people who care about your happiness. We have reason to be angry but expressions of anger do not solve problems. Do we want to solve key problems or release emotional energy? Sometimes we can’t do both at the same time.

The Northern political establishment does the actual work of making itself available for statecraft regardless of how mediocre their outcomes have been. It takes time to invest in structures that deal with different blocs of the international community and does this in the name of the Muslim North. The South does nothing of the sort.

The international community deals with over 200 countries and will take advantage of anything that simplifies its attempts to meet its goals. If the South and the Middle-Belt want to make progress, they’re going to have to unite and develop their own institutions and strategies for para-diplomacy. Para-diplomacy is the act of subnational or regional entities being involved in international relations and it allows regions, states, and even cities to push for their goals about trade, investments, security, politics.

There were pro-Buhari Economist articles in 2015. Now you have pro-El-Rufai Economist articles in 2021.

It is not going to stop. We might as well get smart about how these things are done.

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

There are no comments at the moment, do you want to add one?

Write a comment