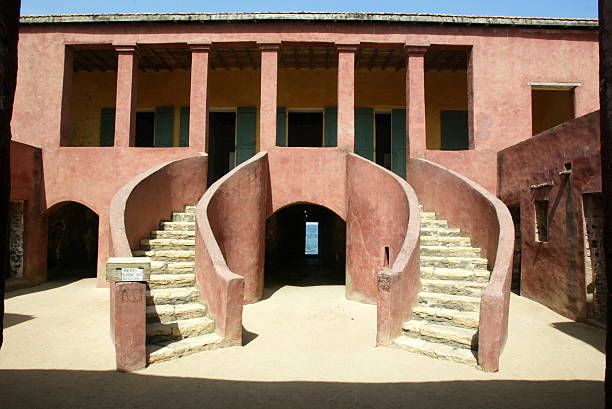

The House of Slaves, built in 1776, stands as a memorial to the Atlantic slave trade

It was Thursday, December 4th, 2025. I spent the morning on Gorée Island, just off the coast of Dakar, Senegal, in West Africa. It’s a place of startling, almost disarming beauty at first glance. Bright bursts of color spill over the walls. There’s a constant, soothing sea breeze. I could hear people laughing somewhere down a cobbled road, their voices carrying the simple joy of the present.

Then you step inside the House of Slaves, one of the old quarters where Africans were held captive before being forced onto ships headed to the Americas, and the entire world seems to contract. The easy air instantly feels heavier. Your imagination, unbidden, starts doing work you didn’t ask of it.

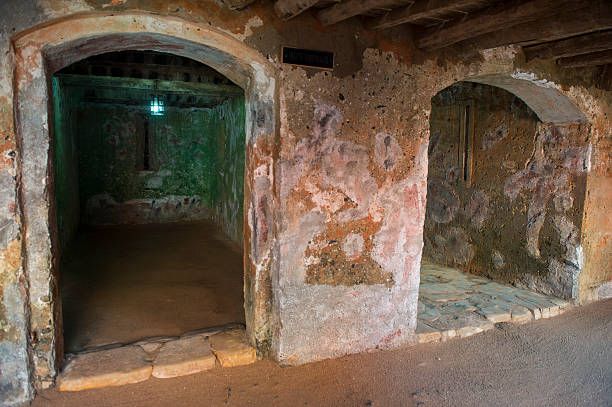

I stood inside one of those cramped cells and felt a physical tightening in my chest. I tried, perhaps foolishly, to picture what it was like to be here in the eighteenth century—not as a visitor with a ferry ticket, but as someone trapped, with no future left to claim as your own. Families torn apart by the whim of a ledger. Human beings systematically reduced to units of trade. The very stone floor beneath my feet, worn smooth by generations of despair, still remembers things no history book can ever fully carry.

It shook me in ways I am still diligently sorting out.

There is something profoundly unsettling about being confronted so directly with the brutality of the past. You start asking questions you don’t always want honest answers to. What does forgiveness even mean in the face of suffering on this scale? Is it possible? And if it is, what rigorous demand does it place on us? I caught myself cycling relentlessly through anger, sorrow, intellectual understanding, then right back to a primal anger again. Perhaps that oscillation is normal. Trauma this old has a way of echoing, not fading.

Advertisement

Slavery, in our comfortable modern consciousness, is often treated like a completed chapter, sealed shut behind neat museum plaques. But standing in those silent, hollow rooms, you realize it wasn’t just an institution; it was a comprehensive assault on the human spirit itself, executed on a scale that is nearly impossible to absorb. It was systematic, intentional, and brutally efficient. Man’s staggering capacity for cruelty is one of the hardest truths to swallow, and yet here we are, centuries later, still trying to make sense of what that truth means for our lives today.

Part of me believes forgiveness isn’t about the moral failure of forgetting. Forgetting would feel like a betrayal of everyone who passed through those doors. What is more meaningful is remembering clearly enough that we are compelled to insist on renewal.

We must try to build something fundamentally better, staying fiercely vigilant about the subtle, structural ways injustice can slip back into the world, now dressed in different, more sophisticated clothes.

Advertisement

Because even though the transatlantic slave trade ended, the cruel mindset that allowed it to exist didn’t vanish overnight. You see its residue in structural inequalities. You see it in whose pain is taken seriously and whose is dismissed. You see it in a global order that still feels profoundly skewed. Justice, equity, and fairness sound like straightforward, beautiful ideals, but living up to them requires constant, often painful, recalibration. Maybe that is the real, ongoing work the past demands of us.

And of course, modern slavery is still with us. It simply hides better. Forced labor. Human trafficking. Exploitation baked into supply chains. The quiet desperation of people trapped by poverty or manipulation. It’s not as visibly etched into the stone walls of Gorée, but the human impact can be just as devastating. We like to tell ourselves we are more civilized now, but the truth remains deeply uncomfortable.

Then there is the more subtle kind of bondage; the mental sort. The inherited narratives people carry. The way entire populations can feel defined and contained by historical trauma. How self-perception is shaped by centuries of being told you are less than you are. And sometimes, the heaviest chains come not from others but from within: the paralysis of doubt, the quiet chokehold of shame, and the constant pressure to validate your existence in a world that often refuses to see your full humanity.

Self-liberation is its own deliberate journey. It doesn’t happen in a single, inspiring moment of epiphany. It grows slowly, like an internal muscle being strengthened. You begin by recognizing inherited beliefs that never served your purpose. You challenge the characterizations others try to place on your identity, your abilities, and your future. You refuse to shrink just because history once tried to compress you.

Advertisement

Faith often helps anchor that journey. At least it has for many people I know. Not necessarily the narrow kind tied to rituals, but a deeper, fundamental trust that the human heart can recover from things that should, by all logic, break it. It is the faith that dignity is not something that can be permanently taken away. It is the faith that hope can be an act of resistance rather than just simple naïveté.

As I took the ferry back to Dakar, the crossing felt strangely quiet. I kept thinking that maybe freedom isn’t simply the absence of chains. Maybe it is the willingness to look at a past soaked in suffering and still find the moral courage to imagine a future rooted in justice. It is choosing courage over bitterness. Renewal over resignation. It is holding memory without submitting to bondage.

I think a vital part of me was still standing in that cell, listening. And perhaps that is exactly where the profound work of healing begins.

—————————————

Advertisement

Adebawo is an accomplished business leader and communications expert with extensive experience in the oil and gas industry. He currently serves as the General Manager of Government, Joint Venture, and External Relations at Heritage Energy. Adebawo is also an author, scholar, and ordained minister, known for his writings on socioeconomic

issues, strategic communication and leadership.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.